This past week, the sports world was once again subject to the glitz, glamour, and spectacle of the NFL Draft. The gorgeous outdoor extravaganza of an open-air amphitheater backing onto Lake Erie notwithstanding, the event was a not-so-subtle reminder of the money the NFL has at its disposal — and the talented public relations machine that it equips said money with. Now I’m not a football guy at all (I saw clips of Trevor Lawrence for the first time last week, and confused him for one of several hundred similar dudes I’ve hanged with at a late-aughts Flaming Lips concert), but I can’t help but stare slack-jawed at the show the NFL puts on. It is a hype machine on caffeine pills.

The Draft Theatre in Cleveland is the largest stage structure the NFL Draft has ever assembled. pic.twitter.com/sDHZhX6Pcv

— Camryn Justice (@camijustice) April 27, 2021

And, of course, why wouldn’t it be? Hype — and its more temperate but sensible little brother, Hope — is what professional sports drafts are all about. You get a team like the Jacksonville Jaguars, or the Detroit Pistons, or the Pittsburgh Pirates, and you dangle the sweet carrots of “game-changer”, “generational talent”, and “immediate impact”, and the fanbase salivates. What could be more tantalizing to fans of a one-win team in Jacksonville then seeing pictures of a buffer Sean Penn from Fast Times at Ridgemont High, hearing him called “the best quarterback of a generation”, and knowing you get to see him on a weekly basis starting immediately?

Of course, as a fan of baseball, the draft is an entirely different process, and a thoroughly different experience. Baseball fans know full well to temper that immediate adrenaline shot of hope with the sober chaser of reality: in baseball, even the most talented, ballyhooed prospects in the draft are still unlikely to make an impact for two or three years at least.

I’ve read many an op-ed over the years — and in particular since the infamous 2009 Mike Trout draft — opining about how to make the MLB Draft an event with more gravitas. Not akin to the NFL Draft necessarily (do we really need a red carpet walk-up for every pick?), but something a little more energizing and motivating. A spectacle, if you will. I’ve taken three of the most common draft points of contention, and evaluated the likelihood that they will change or be modified anytime in the near future.

Make the Amateur Draft International

Increasingly, baseball has become a sport that is heavily invested in its international talent pool. Of the four major North American sports, only hockey casts a wider net across the globe for its talent, and baseball’s net is much more capacious. Opening Day rosters this year featured 256 players from 20 different countries and territories outside the United States, the third-highest number in recorded baseball history. Of MLB.com’s top-25 prospects for 2021, five were from outside of the United States and Canada and thus, were players ineligible for the amateur draft. This includes baseball’s top-ranked prospect, Wander Franco (Dominican Republic). This number is actually down from what it was in recent years, but is nevertheless indicative of how some of the best prospects in baseball continue to be young men who are ineligible for the amateur draft.

Currently, one must be a resident of (or attended an educational institution in) the United States, Canada, or a U.S. territory, such as Puerto Rico, to be eligible for the draft. These rules obviously exclude the burgeoning baseball hotbeds of Central America, and consistently-stellar exports from East Asia, which means that a massive swath of the age-eligible talent pool is absent from the draft reckoning. Although each of these regions have their own leagues, rules, and priorities, it is fair to say that the best players from these regions predominantly desire to play in MLB.

The availability of bonus pool money for small-market teams is one of the ways that MLB tries to level the playing field for International Free Agents — a player pool which in recent years included guys like Ronald Acuña Jr., Juan Soto, and Fernando Tatís Jr. Results and sentiment on this front have been mixed. On one hand, there is a desire on the part of players and international trainers to have the ultimate say on which market they will sign with, and this may (hypothetically) skew players in favor of certain markets. The free market aspect of this is akin to what you get in international soccer, and is a system which would seem to have the greatest boon to players. The results aren’t as lopsided as those you see in international soccer, though — just take Franco, who signed with one of the smallest market clubs in all of baseball, despite being so highly sought after.

On the downside, the “Wild West” mentality of the system can occasionally see players as young as 13 or 14 years old commit to teams, which is ill-advised at best, destructive at worst. With MLB teams continuing to invest in international scouting infrastructure, including scouting and training camps and relationship cultivation with the international programs in certain nations, international recruitment has become an arms race. On one hand, this is a level of strategy that is unparalleled in North American sport; on the other hand, it means that we may increasingly see situations like what the Tigers did with Roberto Campos in 2019, when they ostensibly paid him to exclusively audition for them, hidden away from other teams. Now 17 years old, Campos has been a highly-regarded prospect in the Tigers system since 2019, but still isn’t likely to debut for the team for at least another three years. The clandestine nature of having him, at 15, ferreted away in some corner where only they can see him, would seem to run counterproductive to competitive balance and the market dynamic.

MLB has started to get buy-in on an international draft from an unlikely source: some of the buscónes who train Latin American players. Why? They're tired of seeing 13-year-old children agreeing to deals with major league teams. News at ESPN: https://t.co/luTZweD9X5 pic.twitter.com/uB19kBATSJ

— Jeff Passan (@JeffPassan) May 10, 2019

Baseball owners have been proposing a separate system for an international draft for years, with the most recent suggestion in 2020 suggesting a parallel event to the current amateur draft, rather than an integrated one. From a spectacle standpoint, the general populace doesn’t often know much about the kids getting signed at 15 years old out of the Dominican Republic, Cuba, or elsewhere. There also doesn’t happen to be a great deal of tape, trackable statistics, or generally-accessible info to nerd-out over, so even if these kids were included in their own amateur draft, it’d still be a draft largely of John Does. But if the MLB implemented a similar age limit to what we have in the current amateur draft (high school graduates or 21), then at least there would be more of a chance for these kids to percolate.

POSSIBILITY: Moderate

Change Universal Eligibility to At Least One Year of Collegiate Play

Amateur drafts are a funny thing. On one hand, teams pour millions of dollars worth of resources, over the course of several years, into ensuring an outcome. Players will be tracked for years on end, with statistical spreads akin to that of a professional, all in an effort to guarantee the most accurate prediction. The key word in all of that, of course, being prediction.

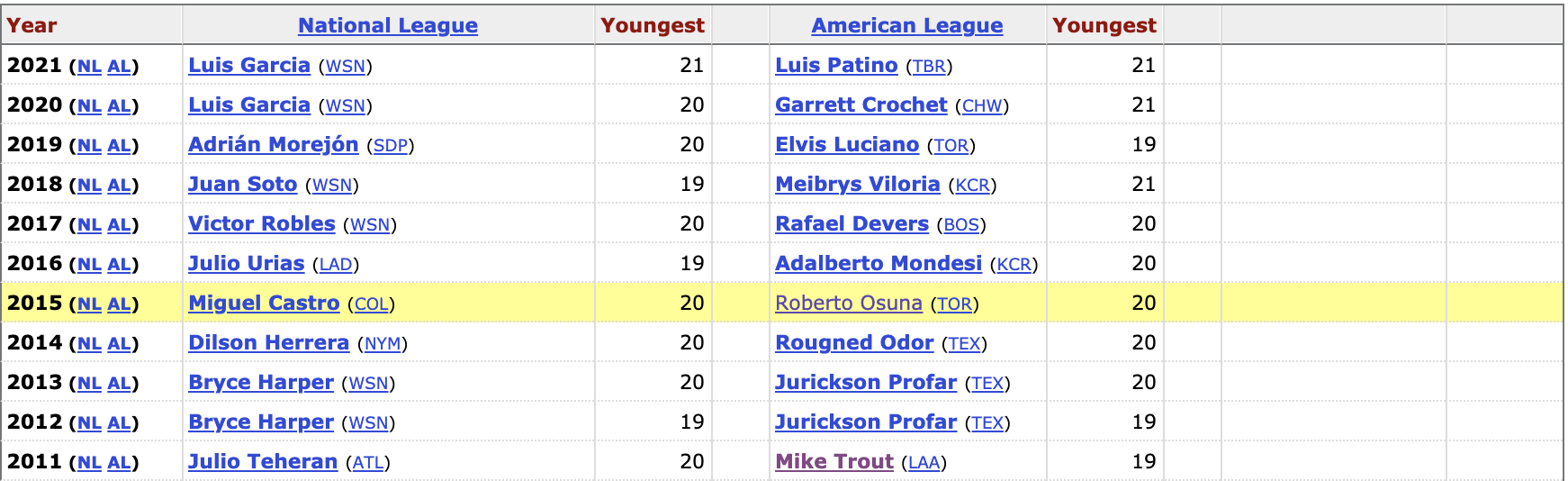

But doesn’t all of that get thrown out the window when you’re evaluating 18 year olds? After all, what does an 18-year-old really know about themself? You should’ve seen my wardrobe at 18. And my work ethic. And my sleep schedule. Now, I’m not suggesting that elite-level athletes don’t have a vested interested in getting more than six hours of sleep or a diet that doesn’t involve six days a week of Subway lunch, but these are still just barely adults. Take a look at the list of the last 10 years of the youngest player in MLB. On this chart, you’ll see a cadre of international signees, and just three players from the amateur draft: Bryce Harper, Mike Trout, and (for some reason) Garrett Crochet:

Currently, there are different tiers to amateur draft eligibility. Like the NFL and NBA, there is a tier of college draft eligibility, but the way baseball does it is certainly unique. Current rules mandate that a player must complete a minimum of three years at the educational institution to which they have enrolled, or reach the age of 21, in order to be eligible. This seems entirely fair to the collegiate systems that invest in these players, many of whom will not actually contribute to their team until at least their sophomore seasons. On the other hand, it means you’re handcuffed to the system until at you’re at least 21, which means that the upper echelon of talent are carving off at least two years of earning potential.

What makes the MLB system unique is the hybrid high school eligibility system. Currently, a high school-age player is eligible for the draft if he has graduated high school, and not yet played a collegiate game. Now, this may seem like the least efficient way to guarantee outcome — the younger you invest, the higher the risk — but that doesn’t deter clubs from taking the plunge when they feel the risk is worthwhile. Of the 37 picks that comprise the first round and the Compensatory Round, 13 were high school graduates who had not yet played college ball. This is the same amount selected from those combined rounds as in 2019, both of which represent the lowest amount of high schoolers taken in the first round this century. 2020 also saw the highest pick of a high schooler taken off the board, with Robert Hassell going to San Diego at #8.

The 2020 draft was considered a particularly strong year for collegiate players, and it is unlikely to be a similar situation in 2021 — three of the consensus top five players in the forthcoming draft (Jordan Lawlar, Marcelo Mayer, Brady House) are high schoolers. One of the deterrents for clubs to take high school-age players in the past has been the reticence to draft a kid who could, theoretically, rebuke them almost immediately for college ball. The most significant recent instance of this was, of course, Brady Aiken, who was taken first overall in 2014 by the Astros, but chose to forego signing and enter collegiate studies instead. He was drafted by Cleveland at 17th overall in 2015, and has thus far not proven to be an MLB-caliber arm. Instances of this are much more common with the high schoolers taken in the late rounds of the draft, and in the last two drafts, we have not seen an instance of a high school graduate first rounder foregoing the comparatively lucrative MLB signing bonuses offered in order to attend college.

Currently, teams are allocated bonus pool amounts in accordance with how much they’ve spent in previous drafts, combined with an annual rise (or deduction) proportional to the revenue reporting of the league. COVID obviously messed around with such projections and numbers for the 2020 draft. For 2021, teams have a designated bonus pool and international slot allotment that is a hybrid of a few different systems, and which has taken into account the falling revenue of 2020 due to the pandemic. The largest combined pool allotment this year goes to the Baltimore Orioles at $11,829,300, while the largest draft pool allotments go to the Tigers and Pirates.

The Pirates and Tigers have the largest bonus pools for the 2021 MLB Draft while the Astros by far have the smallest pool. Eight teams, including the Pirates, have the largest international bonus pool for the '21-'22 signing period.

All the numbers: ($)https://t.co/dMTznh6nRT

— JJ Cooper (@jjcoop36) April 2, 2021

But pool allotment doesn’t often factor into the willingness for teams to take chances on high school prospects. As with the international players, such a desire often comes down to control. The last high school graduate to go first overall was Royce Lewis to the Twins in 2017. A commit to UC-Irvine, the Twins turned around a contract for Lewis in rapid fashion — within a week, he had signed a then-record (for a high schooler) $6.725 million deal.

Consider the incentive that this kind of money gives an 18-year-old. Sure, college may offer a chance for you to more carefully hone your skills, not to mention the chance to work towards a degree and reckon with a life after baseball — but to ostensibly be gifted over $6 million at that age, on the basis of your talent alone, is more than most kids could possibly dream of. In the years since, Lewis has floated between Low-A and AA ball, and has been just OK. His numbers at Double-A Pensacola in 2019 were fine — .231/.291/.358 with 2 HR, 14 RBI, 6 SB and 12 SBH in 148 PA. Unfortunately, he suffered a torn ACL this past season, and has likely been pushed back for his debut to at least late 2022, although 2023 seems more realistic.

Royce Lewis successfully underwent reconstruction surgery for his torn right ACL yesterday afternoon at the Mayo Clinic, conducted by Dr. Chris Camp, the #MNTwins announce.

— Do-Hyoung Park (@dohyoungpark) February 27, 2021

The same can be said of 2016 first overall pick Mickey Moniak, taken out of high school, who made his long-awaited MLB debut last season. In 46 MLB PAs, he is slashing .154/.283/.231 with 1 HR and 18 SO. There is real question in MLB circles as to whether Moniak can be an everyday MLB player. If this is indeed the case, it is an enormous wasted opportunity for the Phillies, who are in their competitive window right now, and would ideally see a player of Moniak’s pedigree and hype supplementing the lineup this year

By way of comparison, consider the output of the 1st overall picks from 2016 in the three other major North American sports:

| NFL | NBA | NHL |

| Jared Goff, QB, LA Rams | Ben Simmons, G, Philadelphia | Auston Matthews, C, Toronto |

| 69 GS, 42-27 career record, 107 TDs, 2x Pro Bowl | 270 GS, 16.0 PPG, 8.1 REB, 3x All-Star | 330 GP, 197 G, 348 Pts, 3x All Star |

In each of these cases, you have a guy who has made a foundational impact on his franchise. Ben Simmons is a cornerstone piece. Auston Matthews is one of the five best players in the NHL. I did a double-take when I saw Jared Goff here, because it feels like he has been in the league forever, but it must be that I’m just getting old.

Now, baseball players traditionally have a longer incubation period, and the likelihood of any player making as immediate of an impact on his team as these three did is low. And, to be fair to Moniak, it’s not just him that franchises are waiting on — from the 2016 first round, the games played leader is Nick Senzel (taken second overall), who has hit an underwhelming .245/.308/.403 with 15 HR and 55 RBI in 577 career PAs. Kyle Lewis, taken mid-first round in 2016, just won Rookie of the Year last season. A vast swath of guys from that 2016 draft have yet to make their MLB debut — and many won’t. An important note? Of the 41 first round picks (including the compensation and competitive balance rounds), 20 were high schoolers. Of those high schoolers, Ian Anderson (#3 OA), Alex Kirilloff (#15 OA), Gavin Lux (#20 OA), and Dylan Carlson (#33 OA) are just now beginning to carve themselves out solid careers. But none are a “sure thing”.

You could point to 2016 as some combination of weak draft class and poor scouting, but it is emblematic of what has become a real problem in MLB circles. For a sports whose prime years tend to be later than any of the other major sports, judging an 18-year-old seems risky at best, and a loaded-dice crapshoot at worst.

The solution may well be to consider doing what the NBA did not too long ago, and eliminate high school eligibility entirely. This will be deeply unpopular with many high schoolers, college programs (who will loathe a one-and-done mentality), and members of the players association, but the goal of the draft — at least the way its currently structured — should be to give hope and possibility to teams drafting near its top. There is little deterrent — beyond precedent — that prevents teams from taking a chance on an 18-year-old high school greenhorn, so perhaps it is time for MLB to consider implementing a minimum college participation rule. College players still aren’t a sure thing, but mitigating the risk is important here, not to mention saving 18-year-olds from the inordinate and wholly unfair dump-truck loads of pressure that are heaped on them when taken early in the 1st.

POSSIBILITY: Low

Turn It into a TV Spectacle, Starting with Draftee Attendance

Everybody remembers the Mike Trout story from the 2009 draft. A much-lauded draft class, an in-studio event hosted on the MLB network, and the best that the network (and league) could muster was one (1) attendee to the actual event. Now, that attendee just so happened to turn into one of the single greatest players in baseball history, but the story of Mike Trout’s agonizing in-person wait to be selected at #25 overall spoke to just how little import the players (and league (and networks)) gave to the draft.

That has changed in recent years, with the network hosting a much better-produced and hyped event, and we have seen a few more players make the trip to Secaucus, New Jersey for draft day. However, commitment is still microscopic compared to the other major sports. A draft is supposed to be about giving visible, tangible hope to a fanbase that just suffered through a 60-some-odd win season. Bless the cadre of analysts MLB network has, but not having the kids in person to do the walk up, the awkward jersey hoist alongside Rob Manfred, and the post-draft interview with Harold Reynolds and the gang hurts the product. A studio audience full 0f angry Knicks — er, Mets? — fans would help, too. But we need something to chew on.

This is a moment for the kids, of course, and shouldn’t they want to be there, in the spotlight? But it’s important for the Pirates fan, or the Tigers fan, to see the light at the end of the tunnel in a more tangible way than through a brief highlight package and grainy zoom video from their living room. If for optics and interest level, at least! COVID-willing, this seems like a no-brainer.

MLB made a smart move this past off-season in moving the draft to All-Star weekend. There will be no games to obfuscate fan interest, and the draftees will get a larger and more significant spotlight than ever before. But why not consider a rotating cadre of host ballparks, akin to what the NFL and NHL do? Make it a desirable event to host. Make it a weekend of celebration. Make it matter, man!

POSSIBILITY: High (Mile-high, even)

Featured image by Doug Carlin (@Bdougals on Twitter)