Despite being just 28 years old, 2021 feels like the culmination of a long and winding road for Carlos Rodón, who’s preparing for a duel with reigning Cy Young winner Shane Bieber in his second start of the season tonight. Rodón is currently playing on a one-year, $3 million free agent contract signed with the same team that non-tendered him this past winter, six and a half years after making him the third overall pick in a brutal 2014 draft.

Different mixtures of age and experience beget different perceptions of a pitcher. The White Sox first round selection a year prior to Rodón is also 28 years old, but few players have represented the developmental ideal more than Tim Anderson, who followed a pretty linear path from “toolsy” prospect* to raw big leaguer to acceptably average MLB shortstop to bona fide star. The league’s most recent rookie phenomenon, Yermín Mercedes, is also 28 year old, and his lack of MLB experience commensurate to his age is quite literally part of what makes him endearing. Meanwhile, Rodón plays this season at 28 having already been a superstar, having thrown perhaps the single most dominant game the NCAA had seen in decades (until Kumar Rocker and Jack Leiter came along), having been viewed as a savior and as having enough potential that a 3.75 ERA with a strikeout per inning as a 22-year-old rookie was considered little more than a promising start.

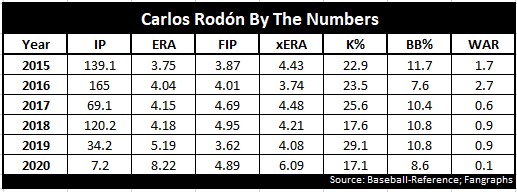

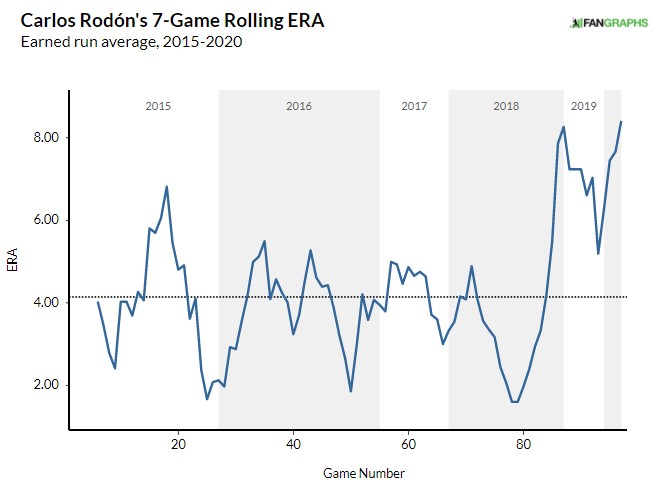

That also means that he’s had time to be a disappointment, a bust, an afterthought, and even at this young age, a reclamation project. Entering last week, it seemed like any hint of the Rodón that went 10 one-hit innings in the ACC championship game was more or less gone. Chicago has gone through quite a few identities since the lefty was brought into the fold, and by the end of the 2020 season, yet another injury-plagued and unproductive season made it look like Rodón would become one final reminder of the mid-2010s failure that led to the current iteration of the White Sox:

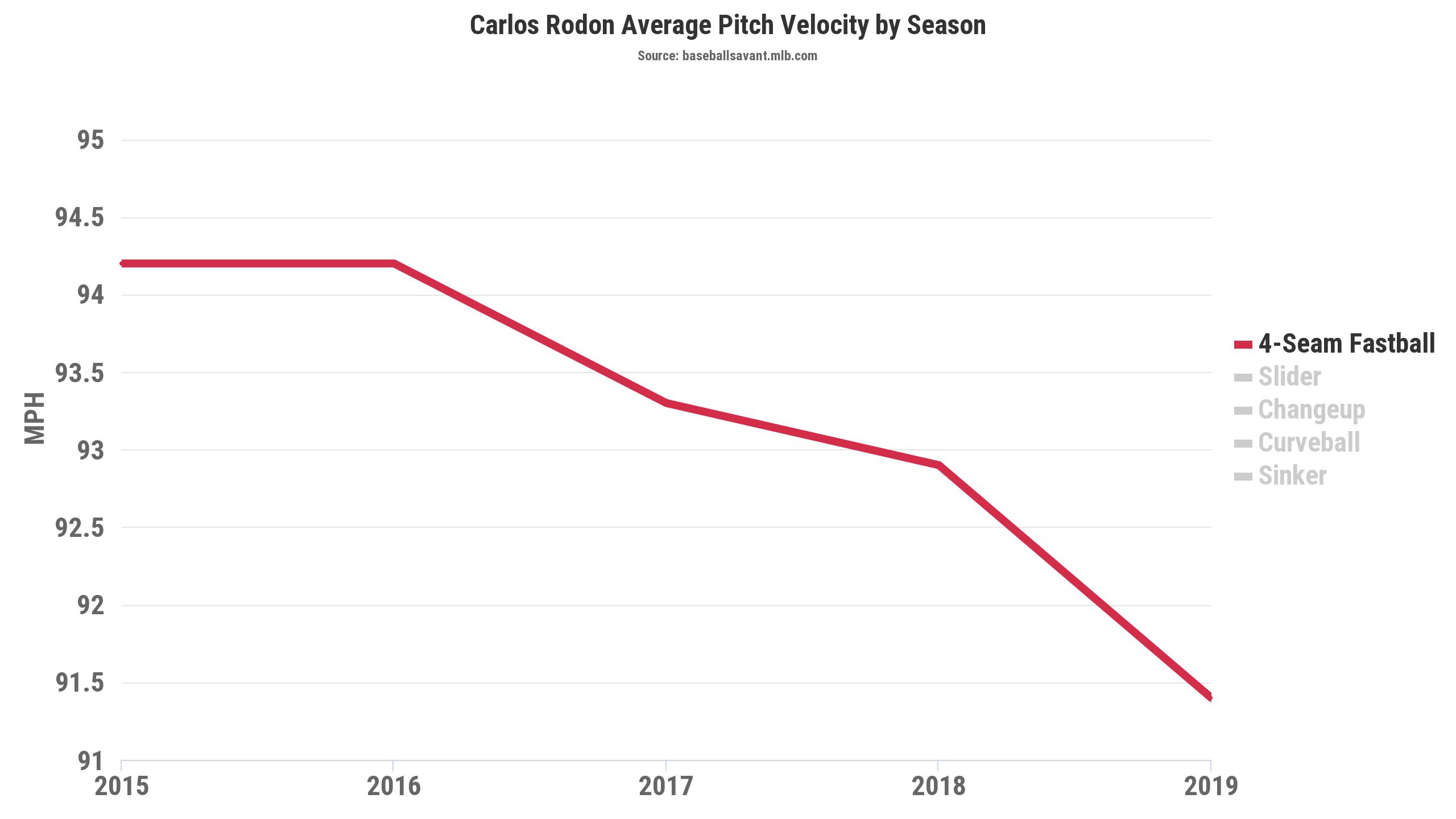

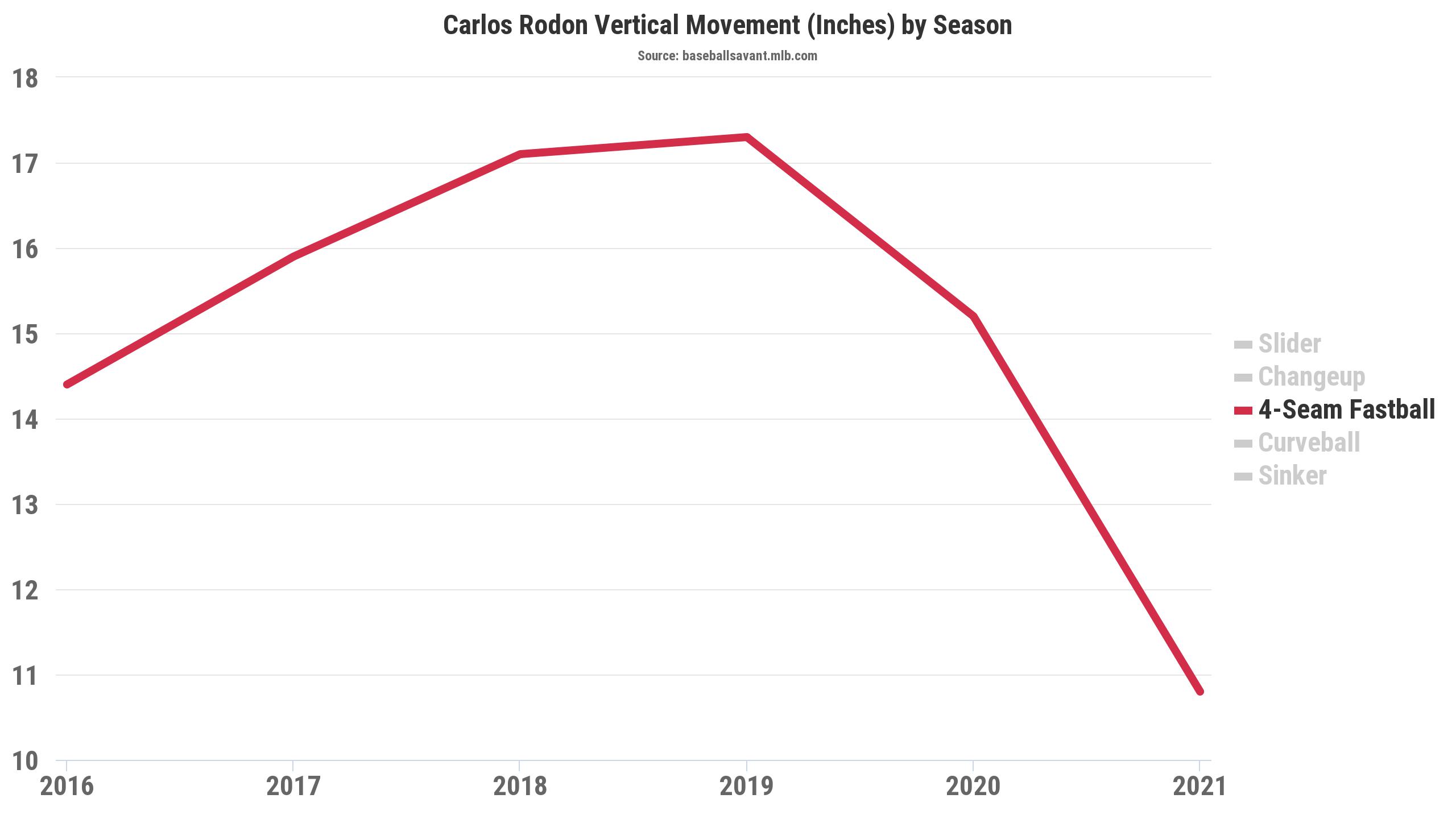

If the numbers make it seem like Rodón ultimately became a very different pitcher than the one that was coming up in 2014, that’s because he was. The jump in strikeouts in 2019 made his FIP look nice, but Statcast data (xERA) didn’t see any real strides being made, and it was clear to anybody watching the games or following the data that the electric stuff that made him such a hotshot prospect simply didn’t exist anymore:

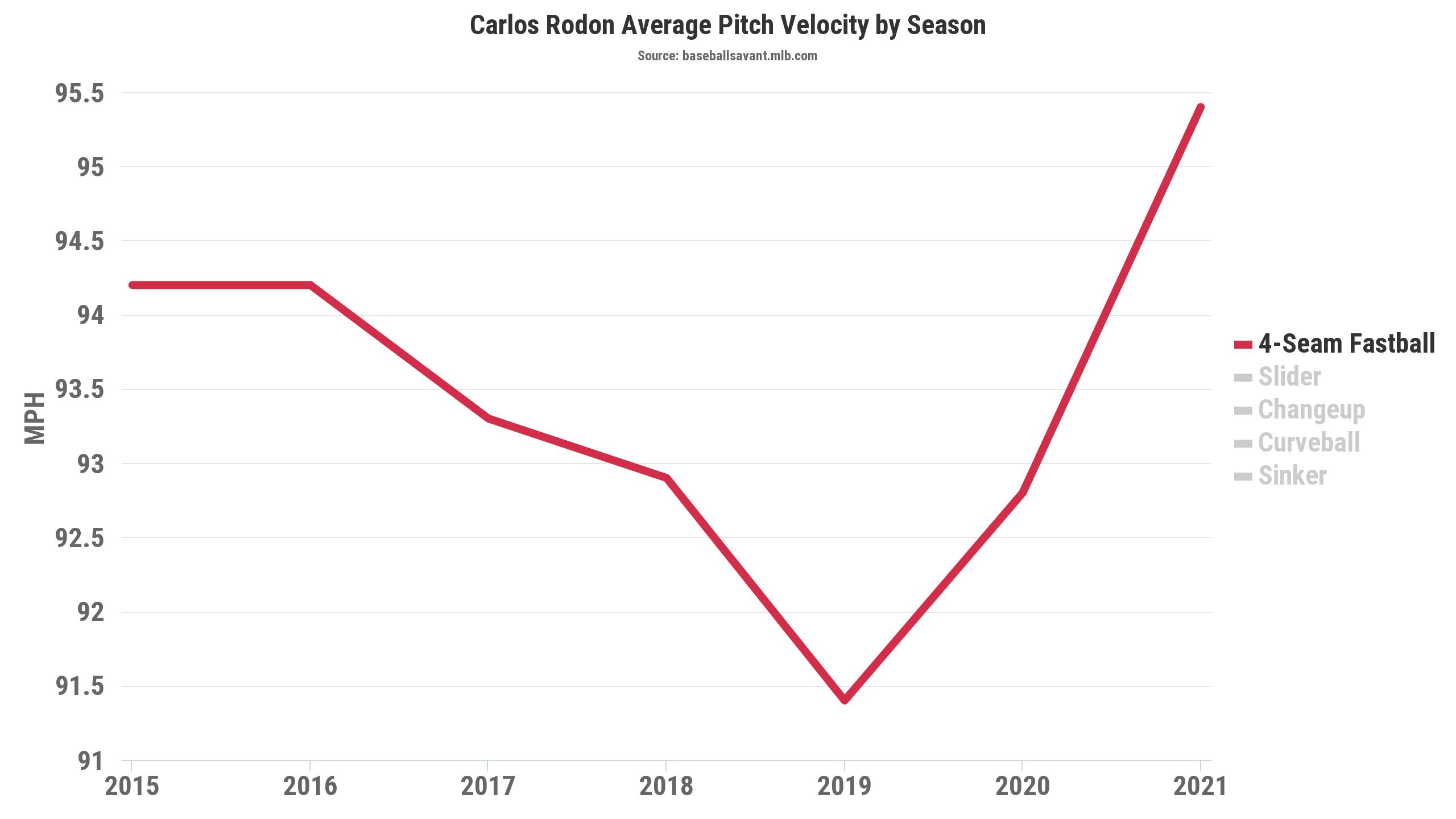

But hey, it’s 2021, not 2019, and I’m sure as shoeshine not writing this article to talk about how much Carlos Rodón sucked in 2019 and 2020. Obviously, I cut that chart off at 2019 for a reason — the full thing gives Rodón’s story yet another twist:

Ooh. Ooh. Yeah, right? While it initially looked like 2020’s velocity spike was just a consequence of his first-ever demotion to the bullpen, it turns out he was hinting at a lot more left in the tank than his pre-Tommy John velocity nadir would indicate.

Now reportedly fully healthy, career-endangering “wake-up call” in hand and having had a full offseason to remake his mechanics to better use his thick lower half (a common adjustment after Tommy John and other arm surgeries, as elbow and shoulder problems are frequently caused by the player’s arm having to shoulder too much of the load (ha) in their delivery), it seems that Rodón’s last chance with the White Sox may beget a few more of them. He teased a new version of himself in March, where he allowed just two runs and struck out 16 with a single walk in 13.2 Cactus League innings. Most of those innings came without the benefit of a TV radar gun or any publicly available data, his first start of the regular season showed that there was most certainly some fire at the source of that smoke:

In case you missed it last Monday, that was five innings of two-hit ball against Seattle, striking out nine and keeping the seamen off of the scoreboard for the team’s second win of the season. That was just the second time since 2016 — and fifth for his career — that Rodón struck out nine or more without allowing an earned run.

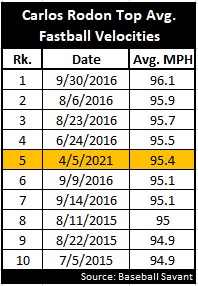

Look, most of us have seen far too much baseball to read super-duper closely into individual starts, and the first start of the year is always particularly tempting and ripe for overreaction. But it should have been instantly clear to anybody watching on Monday that independent of the results themselves, this was a version of the left-hander that hadn’t been seen in quite some time. Here’s a little context: the 95.4 mph he averaged on his fastball last Monday wasn’t just one of his hottest days in years, it was one of his hottest days ever:

Even more importantly, that velocity seems to have come with a huge jump in movement, too. Even when Rodón was sitting in the mid-90s early in his career, he wasn’t getting a whole lot of ride on his heater. Now, not only is the velocity back, but it’s also got a full five to seven inches less drop than it did before:

It’s hard to guess with only a game’s worth of already-limited data, but the most plausible explanation for this is that over the past couple years, Rodón has become one of the best in the game at spinning his fastball efficiently. This means that on a very minute level, he releases the ball in such a way that most of the spin he puts on the pitch actually contributes to its movement, which isn’t always the case. In Rodón’s start on Monday, his average spin efficiency was 97%, a two-point jump in where he was measured at last year and would have ranked in the top 20 of all starters in 2020 over the full season.

In terms of raw spin, his fastball usually checks in between 2,250 and 2,300 RPM, which is actually quite a bit below average for his velocity. But with that kind of efficiency (and a modestly-tilted 11:15 spin direction), it doesn’t need exceptional spin to get enough rise to miss bats up in the zone. And when a pitcher’s mechanics are strong enough to consistently execute it in tough-to-hit spots, it doesn’t matter much at all — poor Mitch Haniger never even had a shadow of a chance on this pitch:

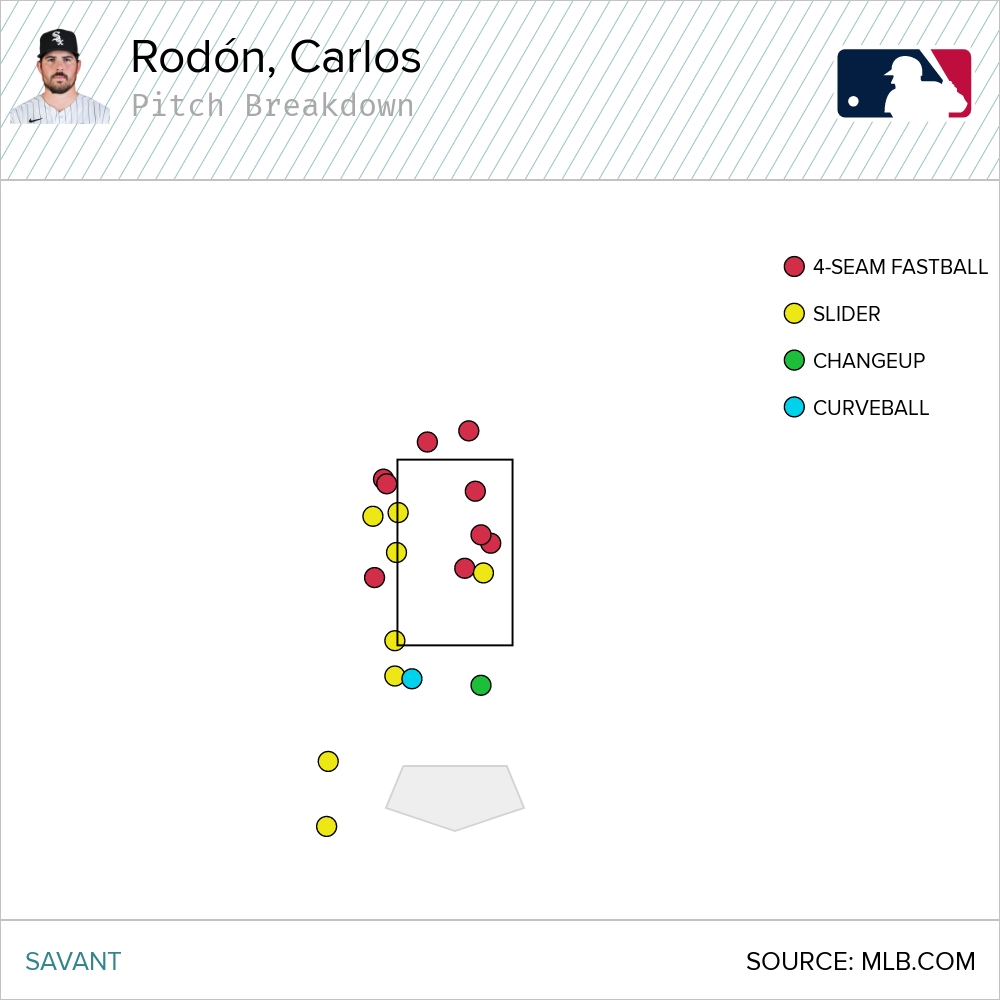

To be honest, I suspect there’s a lot more going on here than I’m initially picking up on. We’re still super light on information, and Chicago’s Saturday rainout dashed my chances of seeing him again before deadline time for this article. Either way, such drastic change in movement profile don’t usually come solely through a velocity bump and small increase in efficiency. Whether it’s arm slot or approach angle or something else — it might be worth noting, for example, that Rodón’s fastball in 2020 had one of the steepest vertical approach angles in the league — there clearly some things I’m not accounting for. The why might not even matter all that much, at the end of the day. Either way, Rodón is fooling hitters pretty badly, because the stuff Seattle was swinging and missing at weren’t even close to being hittable pitches, for the most part:

Some of those sliders were particularly egregious. I mean, come on:

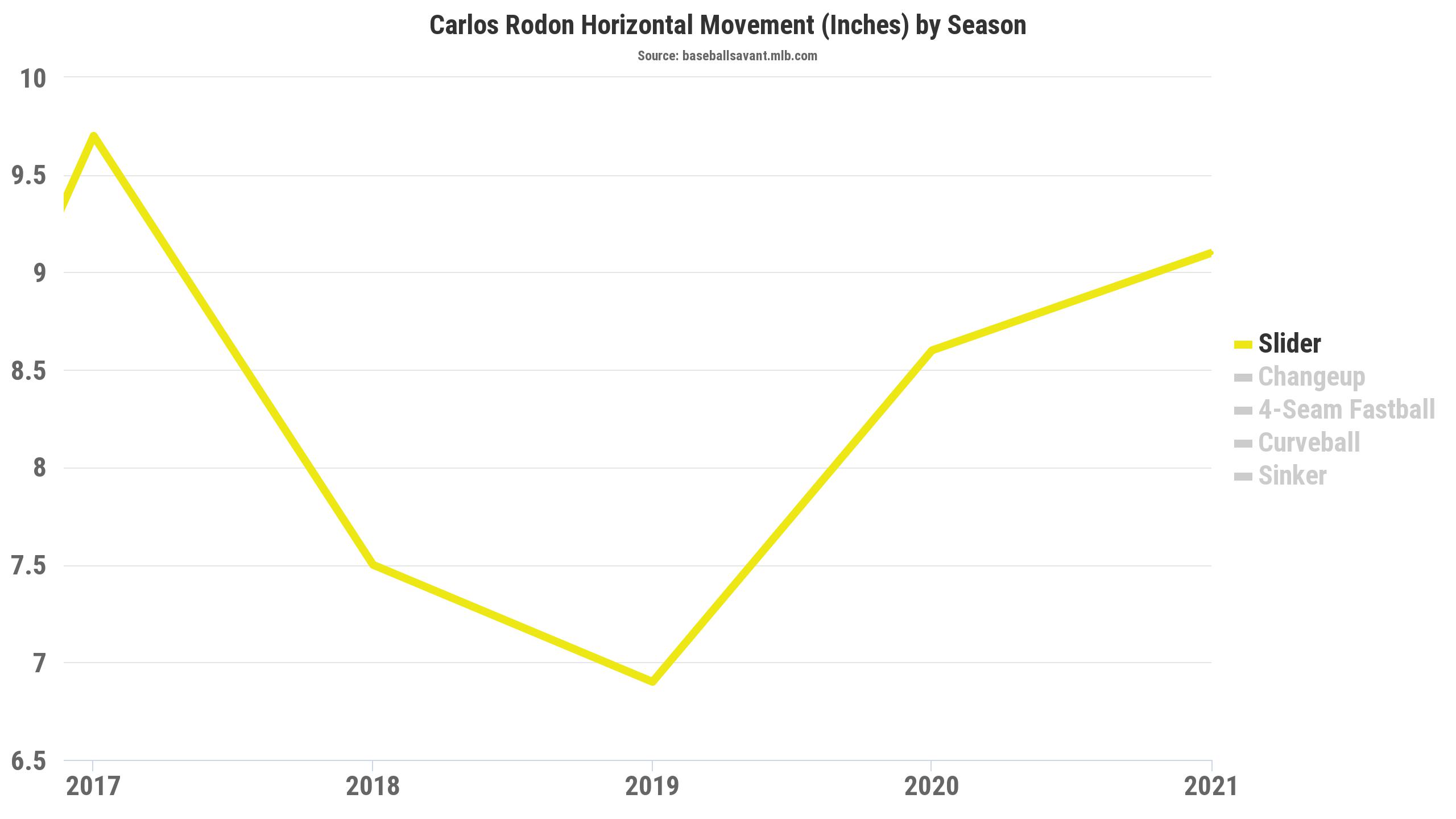

That slider has been Rodón’s calling card since his college days, and that much hasn’t changed. The return of his velocity also seems to have restored some of the pitch’s horizontal bite, losing a little bit of drop and averaging more than nine inches of west-to-east movement last Monday for the first time since 2017:

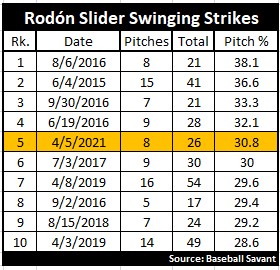

Whatever he did, it certainly worked, because the 30.8% swinging-strike rate on the 26 sliders he threw last week was his highest as a starter in nearly five whole years:

Where might all of these changes be coming from? Honestly, once again, I’m not totally sure. We’ve already covered some of the offseason work he did above, but what does that look like? The most immediately noticeable difference is that after starting his windup square to the plate for the majority of his career, he’s move to a much more closed, hybrid-style stance to start his motion this year. Here he is before delivering a pitch to Clint Frazier in 2019:

And here’s a still from just before his brutalization of Haniger that I showed earlier:

Seattle’s slightly off-center camera angle is our only frame of reference right now, so it’s hard to do too much granular mechanical analysis. The best I can approximate from my eye is that Rodón is much more fluid and rhythmic in his lower half movement than he was in 2019, and that like I touched upon earlier, his torso rotation when he delivers is much better synced and timed with his stride, landing, and hip-opening. Here’s the Haniger GIF again, this time along with the fastball to Frazier we see above:

One thing that might hint at the revamped lower-half mechanics is his very first movement. Look at his whole body when he takes a step back with his right foot to start his motion. With the wide-legged stance, Rodón’s first step essentially moves his entire body about a foot to the side, and if you keep an eye on his left foot, you’ll see that with his new setup, his turn towards the plate is a lot simpler. There’s far less extraneous movement, especially when you look at how much longer it takes to get his chest and shoulders in line with the plate. This is where we have to be careful and aware of how camera angles can be deceiving, but the change becomes a lot more clear when you take a freeze frame of where Rodón’s back foot is located right at the moment he raises it to go into his windup’s leg lift:

Simplifying mechanics is usually a good sign, especially when it makes the pitcher looks visibly more athletic, as I think Rodón does here. If anything, the reduction of wasted energy on the gather into his windup ought to be pretty conducive to a velocity. Anyway, shoutout to Estee Rivera of Prospects365 (@esteerivera42) for the helping hand on the analysis. This is all still mostly speculation and eye test. But given all that we now know about the relationship between health, mechanics, and strength/power, the coincidence between newfound health and substantial velocity gains almost certainly indicates that there are some fairly significant, if visually subtle, changes going on here that I simply can’t identify yet.

That’s a lot of stuff to take note of, and we haven’t even mentioned the curveball yet! Did I mention that Rodón has apparently been working on a new curveball, too?

Even when he previously had the velocity to survive solely off of his fastball-slider combination — his changeup has never approached average, from a results or scouting perspective — his reality as effectively a two-pitch pitcher was already the biggest cap to his ceiling. This curveball, recently developed as a change-of-pace weapon, helps solves that problem, and while it has some promise, it’s also clearly a work in progress. Adding in a get-me-over curve to steal strikes early in the count now and then is a fantastic idea for a two-pitch arsenal with suboptimal fastball command. And that’s exactly how he used it, with all five of the curves he threw last week coming on the first pitch of a plate appearance.

Unfortunately, none of them actually landed in the zone — like I said, clearly a work in progress. Still, it’s encouraging that he was willing to try it that often, having literally never thrown one in a regular season game previously. It doesn’t have to be a good pitch for it to be an effective pitch, if that makes sense. Even if it’s only good to be dropped in the zone early in the count, it adds yet another thing to a hitter’s mental checklist when they’ve already got their hands plenty full with the fastball-slider one-two punch. As promising as Rodón has looked at times over the course of his career, he’s never really had that.

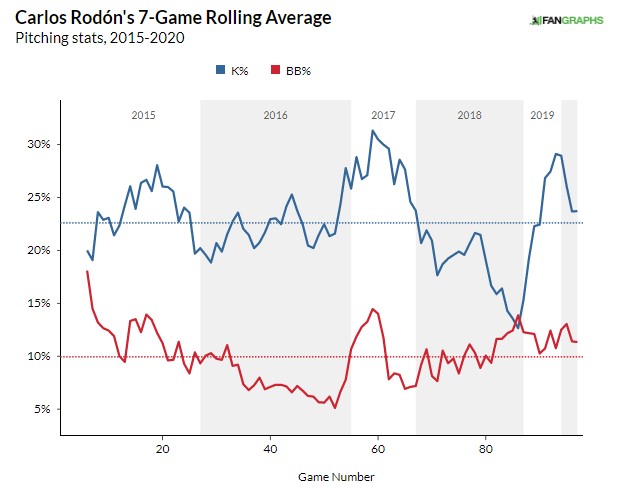

What’s that? Didn’t I just spend the entire first half of the article talking about how his career has largely felt like a disappointment? Yes, of course. But those numbers and that particular narrative don’t tell the full story at all. On the contrary, there are many different ways that one could frame Rodón’s career. So I’ll conclude with one more chart: a simple look at his rolling seven-game ERA and walk/strikeout rates over the course of his career.

In spite of the inconsistency and the mediocre bottom-line results, Rodón has actually been an above-average pitcher much more often than he’s been below average, and he’s actually been genuinely elite at points throughout his career. But the inconsistency shows — in spite of his electric stuff, he’s just never been able to harness his strikeout ability and control at the same time, and it’s the steep inclines in ERA following each extended drop that tend to stick in the hearts and minds of fans, and even analysts. Perhaps the biggest change for the left-hander in 2021 will simply be reminding people that his floor was always higher than he got credit for. Carlos Rodón has been many things over the course of his career, floating somewhere in the ether between draft bust and solid MLB contributor, but he soon may also be a reminder that the long road of a big league career is rarely linear, and that a last chance can just as easily become an opening for many more.

*While the “raw, toolsy” label is probably a fair one to apply to the prospect edition of Tim Anderson, it needs to be acknowledged and noted how such language has been disproportionately applied to (and held against) Black and Latine prospects in ways that implicitly, unfairly malign their intelligence and “makeup,” and that more care and thought needs to be given to the labels we put on players and their consequences.

Photo by Daniel Bartel/Icon Sportswire | Adapted By Aaron Polcare

Fantastic write up! Here’s to hoping this is his year

I never knew “raw, toolsy” meant you were a dumb player or even had ethnic ties. Just thought it meant you had several baseball tools but needed refinement. Come on, lets not go down this road guys.

Also, hitting a HR with a 115mph exit velocity, wouldn’t necessarily constitute as a High IQ move. I don’t think the “non-toolsy” guys were thinking “Hmm man, why didn’t I think of that…hitting the ball to the moon like a missile”. Or rounding the bases with elite sprint speed. Not what I would call a High IQ move either. Speed and power are tools….typically inherited at birth.

Great article, dude. While I agree the sample size is much much too small, I tend to agree with the whole where there’s smoke, there’s fire argument here. The changes can’t be ignored and in excitedly rolling him out there tonight