The shortstop for the Live Oak Base Ball Club laced up his blades, buttoned up his jacket, then raced after a pop-fly before falling flat on his face, sending him careening across the infield. He wasn’t the first player that afternoon to take a spill on the field and was far from the last. This is because, on February 4th, 1861 at 3 pm, the Live Oak and Atlantic Base Ball Clubs faced off in front of 15,000 shivering spectators for nine innings. In skates. On ice.

Welcome to the fantastic world of 19th-century base ball.

The Live Oak B.B.C. of 1860 is a difficult club to figure out. The Buffalo Commercial called them the Champions of Rochester, though evidence of becoming champions of Rochester is elusive. It’s likely “Champions of Rochester” was simply a moniker like The Pride of New York or The Butcher of Blaviken. Of the matches I’ve been able to track down in my exceedingly professional research manner, the 1860 Live Oak Club – also known as the Charter Oaks – went 4-4 with 137 runs scored and 180 runs allowed. Let’s just say the Pythagorean Theorem doesn’t exactly agree with their record, though more games were certainly played. There’s one example of the “muffins” of Charter Oak playing the muffins of the Star. Muffins, if you’re curious, were the equivalent to reserve rosters. Pre-Civil War baseball was wild.

| Oaks | Opponents | Team | Result | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 11 | Excelsior | W | 19-May |

| 9 | 36 | Excelsior | L | 21-Jun |

| 16 | 12 | Manhattan | W | 29-Jun |

| 9 | 27 | Excelsior | L | 9-Jul |

| 25 | 16 | Eagle | W | 24-Jul |

| 36 | 33 | Star | W | 7-Aug |

| 18 | 27 | Excelsior | L | 7-Aug |

| 12 | 18 | Harlem | L | 15-Aug |

Notably, the Live Oaks participated in the Excelsior Club of South Brooklyn’s first extended trip by a baseball team (having a rule of “no intoxicating drinks” during the excursion). This “gallant” club booked passage through six cities giving local clubs a chance to take down the big guys. While Rochester managed to snag a surprising 12-11 win on opening day in the regular season, Excelsior came back with a vengeance during the tour and trounced the Oaks by 45 runs over two games. Champions of Rochester, perhaps, but New York was owned by the Excelsiors during this trip (who would be defeated by the Atlantic Club in a championship series).

From the six boxscores I could track down, the most valuable player of the team is hands down Randolph/Randolf, who played 2d, which is 19th-century speech for second base, presumably). Randolph scored eleven runs over four games and was out only five times, though Oak pitcher Shields should be in that conversation as well. Despite his 19.67 ERA, it was said that Shields pitched “very effectively.” Given the praise bestowed upon him and the competition that he faced twice in the state leading Excelsiors, let’s spitball without abandon and give him a solid if not great 113 ERA+. Of course, some members of the team (not pointing any fingers *cough* Carroll) tended to lapse into “muffanism play” – now permanently in my lexicon for poor play.

| Player | Pos | Games | Outs | Runs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanderhoof/Vanderhoff | 3d | 5 | 16 | 8 |

| S. Patchen | short | 5 | 15 | 12 |

| J. Patchen | LF | 5 | 19 | 8 |

| Randolph/Randolf | 2d | 4 | 5 | 11 |

| Shields | P/short | 4 | 12 | 8 |

| Piper | CF/RF | 4 | 10 | 5 |

| Carroll | 1st | 4 | 13 | 8 |

| Oswald | RF/CF/C | 4 | 14 | 6 |

| Murphy | C | 3 | 9 | 8 |

The Live Oaks could at least complete with the best teams in New York – the crowd considered the Oaks to have “done well” against Excelsior despite losing by nearly 30 runs in one game – but they were never a dominating force. The one area everyone could agree on for the club, however, is they were elite at public relations.

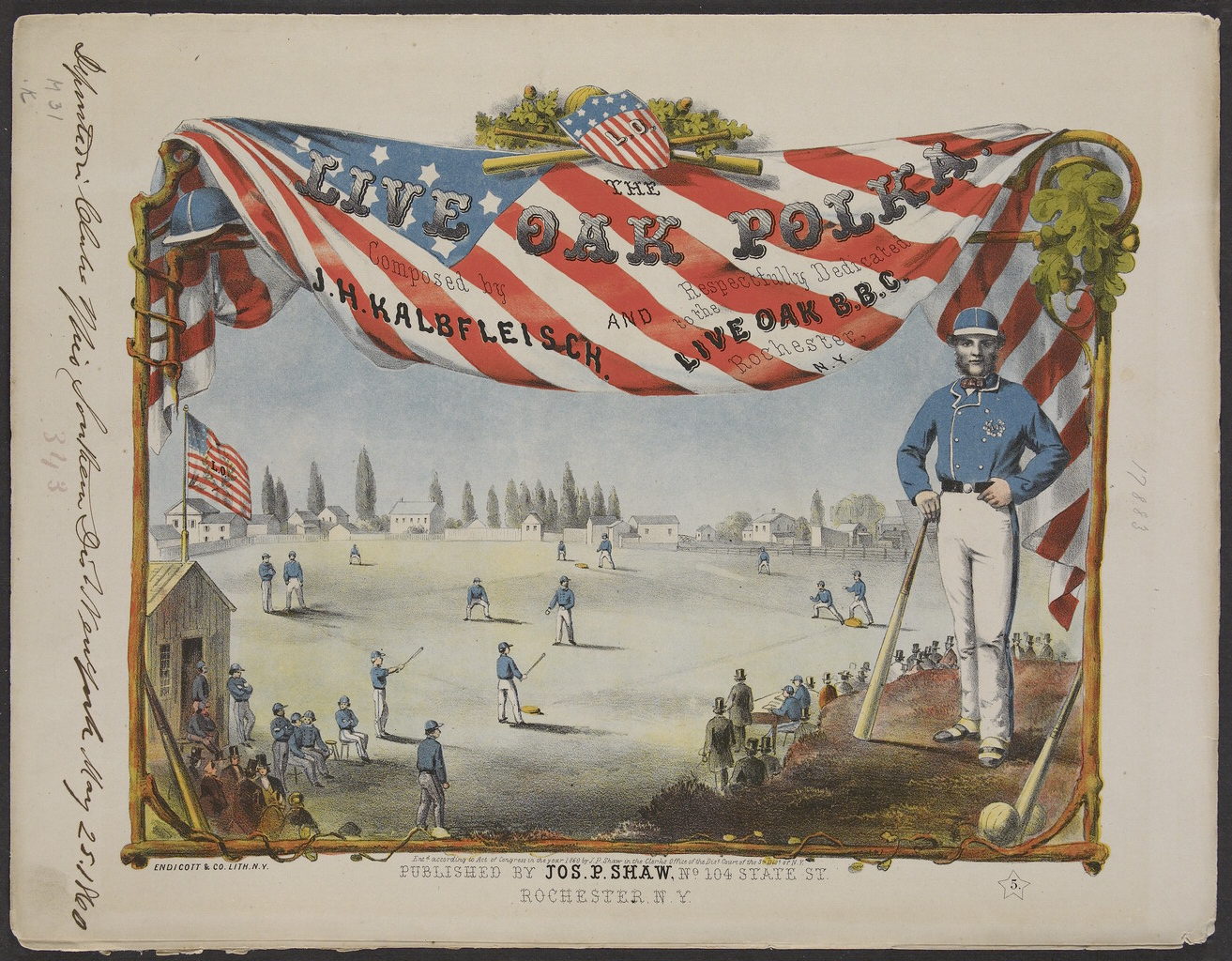

On May 25th, composer John H. Kalbfleisch published the 3-minute long “Live Oak Polka – Respectfully Dedicated to the Live Oak B.B.C. Rochester, NY.” Listening to it, and I strongly recommend that you do; you’ll imagine an old-timey moving picture with Live Oak players competing in a proper match of 19th-century base ball while the team dog gets into quite the predicaments. It took the champs at the Atlantic Club another ten years to receive their own Polka—again, it’s easy to imagine jealously slowly eroding clubhouse cohesion over not having a Polka—until the team owner finally gives in and funds a Polka! Undoubtedly true conjecture aside, both Polkas were noteworthy enough to be included in the Library of Congress, where you can see the sheet music in all its glory.

Look deep into the mutton-chopped-eyes of Live Oak man, and you’ll discover the true meaning of base ball.

In September, the ball club continued their PR tour when they were presented with a “unique and beautiful present… a ball three inches in diameter, beautifully finished and made from the Charter Oak. It is enclosed in a beautiful rosewood box” with a nice silver inscribed plate. Sounds neat. We’ll give them points for a wood ball, sure. It was evidently a gorgeous piece worthy of being written about in multiple newspapers. That’s 2 for 2 in the PR department, 3 for 3 if you count their inclusion in the Excelsior’s grand tour.

For their next show on October 27th, the Oaks split into two teams based on who supported which presidential candidate and put on a two-game series. Those teams were Team Douglas and, yes, Team Lincoln. The Champions of Rochester separated their team by political affiliation a month before South Carolina seceded from the Union. I think that warrants a reread. Split their team for two games by political affiliation a month before the disunion of the country. Whew. The early game saw Team Lincoln win 27-17 (it helped that the squad had twice the number of players as Team Douglas). One week later, Team Douglas claimed victory because the Lincoln folks didn’t show up, so on the make-up game Team Douglas, probably miffed at being snubbed earlier, took the win 29-14 despite only having 5 players on the field.

To be a fly on the wall when that decision was made…

The Live Oak B.B.C. had one last surprise for the early sport. Sometime in December, the team put out a challenge for anyone who would take it. According to the Buffalo Commercial, “the Live Oak Base Ball Club of [Rochester], challenge any club in the state to a match at their favorite game, ten men on a side, and match to be played upon skates, at Irondequoit Bay.” They then take it one step further and throw down the gauntlet: “Is there no club in this vicinity able to take on the conceit out of the Rochester champs.” Such hubris simply could not stand!

The Atlantic Base Ball Club, the team that defeated the mighty Excelsiors in the championship series and would infamously (in my mind) rip-off the Live Oak Polka, accepted the challenge, and a date was set for January 24th, 1861. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle drummed up interest in a way only journalists from that time could:

“We are informed that the Atlantic and Charter Oak Base Ball Clubs, will enter into a friendly, but slippery contest for superiority, the players to be on skates, taking all the risks of such breakneck attachments…. for there is an unaccountable desire felt by many to see men do dare-devil feats.”

Naturally, it’s difficult to time a base ball match in winter. A week later, the Eagle updated its eagerly awaited readership:

“Last week we announced that the merry dare-devils of the Atlantic and Charter Oak Base Ball Clubs, proposed a match to be played on skates… Those who looked forward to see any amount of lofty tumbling were disappointed, the slippery contest being postponed by an untimely fall of snow. Next Monday… the match between these agile crowds will be played…”

Ice Skating and Base Ball were both rising in popularity by this time. During the construction of Central Park in 1857, it was required to have ice skating rinks in the planning, and indeed the skating lake was one of the earliest features finished in the park. It was only a matter of time until some brave soul put two and two together, and on February 4th, twenty brave souls finally laced them up.

The Big Game

The frozen pond sat on ten acres nestled between Third and Fifth avenue, and “a good nipping frost” was in the air for this most American spectacle. The 15,000 some odd spectators had a good view “of the ball players, who full of enthusiasm and excitement, dreamed not and cared not for broken bones and bruised flesh.” The prize in all this potential mayhem? A shiny silver ball the size of an ordinary baseball. Worth it.

Having made the challenge to the world in the first place, the Oaks were the home team and took the ice for the top of the first. Oak pitcher Jerome warmed up on the frozen water and readied himself. The fielders around him took their places with red dye being used to mark the bases. Base Ball on ice was about to sweep the country, and the craze would begin with the opening inning. It went exactly how you’d imagine. We’ll let the Brooklyn Daily Eagle paint the picture. “At first, several of the players, in their anxiety to stop or catch a ball, by a miscalculation were brought summarily, and in one or two instances rather unpleasantly, in connection with the ice.” The infield fly rule did not exist for this game, in other words. The Detroit Free Press piled on, “The playing was somewhat mixed on account of some of the best players being the poorest skaters and some of the poorest players being the best skaters.”

By the time the Oaks settled down and figured out this dance on the ice, the Atlantic Club had put up 8 runs in the first. Two frames later, and the score stood at 18-2 (I can’t help but feel the score would be different if ace pitcher Shields and his 19.67 ERA was available. Maybe not better, but different). Rochester, that team who could compete against the best but not win against the best, had to somehow skate uphill.

Both teams skated like experts after the poor first inning according to the New York Times and looked to be comfortable with blades under their feet – I’m sure the players were thankful no one like Ty Cobb, who famously slid into second spikes up, was playing in that game. The Oaks fought back by scoring seven times in the fourth, giving the crowd something to watch. And watch they did—this was the social event of the season. The spectators were full of “misses with their brothers, young maidens with their admirers, and lovely matrons with their legal protectors,” and they pulsed around the field, getting so close many were practically touching the players. Deputy Inspector Folk from the police had to use a large force to ensure orderliness of the game, but no such kind of brew-ha-ha or knuckleduster or rows with a wallpapered pie-eater, which I’ve been assured was a thing, took place.

The Oaks fought hard, chiseling out ten runs in the sixth and slipping in three in the ninth, but ultimately fell to the Atlantic Club 36-27. In all, “no one was seriously injured.” The Live Oak Ball Club would disband at the onset of the Civil War a few months later. (One of the more interesting side stories in this research was watching events unfold in the columns next to base ball. Like the Lincoln election, a slave trader being arrested in New York, President Davis appointing a Secretary of State for the Confederacy, and Great Britain refusing the accept the disunion.)

Towards the end of the War, the team would reconvene before bringing New York-style base ball to Cincinnati later in the decade. Alas, there’s no myriad of connections to any modern-day team, as the Oaks would fade away in the 1870s, lost in the movement of teams and a general decline of base ball in Cincinnati at the time. While the team disappeared, the Live Oak Base Ball Club of 1860 will forever remain fantastic, immortalized in song and frozen boxscores.

Live Oak Polka Image – Kalbfleisch, J. H. Live Oak Polka. Monographic, 1860. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/2009541120/.

Featured Image by Doug Carlin (@Bdougals on Twitter)