In October, I had the opportunity to attend First Pitch Arizona and witness some brilliant minds present about baseball. Outside of the presentations, I had the pleasure of having several side conversations that ranged anywhere from Japanese alcohol to, of course, baseball. One of those conversations was with none other than Nick Pollack, where we talked about how Noah Syndergaard had changed from the 2015-2017 version of himself.

Part of it is defense, as Craig Edwards has pointed out, but his overall swing-and-miss rate has been falling since 2016. The injury sticks out, too, though. To briefly retell the story, in 2017, Syndergaard was dealing with right shoulder and biceps discomfort. After scratching him from a start, the Mets offered him an MRI, which he denied, saying, “I think I know my body best.”

Of course, Syndergaard ended up tearing his lat muscle, which effectively ended his year as a starter.

Upon returning, Syndergaard has continued to be dominant—he’s still one of the most promising pitchers in the league—but he hasn’t been the same.

| K% | BB% | ERA- | FIP- | xFIP- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-2017 | 28.4 | 5.2 | 76 | 66 | 68 |

| 2018-2019 | 24.5 | 5.8 | 91 | 73 | 82 |

Since 2018, Syndergaard has the eighth-best FIP- for starters, and the 12th-best xFIP-, so it’s impressive that we’re even talking about this. He’s basically been a top-10 pitcher by FIP, and yet we’re still wanting more. Well, that’s because from 2015 to 2017, Syndergaard had a 66 FIP- that ranked second in baseball, behind just future Hall of Famer Clayton Kershaw.

If you have followed Syndergaard, you will know that he broke out with an obscene slider in 2016, was hurt in 2017, and then in 2018 it wasn’t as good, before completely losing the feel for it in 2019 due to the rabbit ball. Since it’s what spurred his breakout, perhaps it comes as no surprise that it was one factor in his down 2019.

The main issue with Syndergaard, as I see it, is that he struggled gripping his slider in April, changed his grip which created a slurvier pitch that he doesn't trust, and he can't find the right grip back. He has little confidence in his slider, and thus he's barely throwing it.

— Tim Britton (@TimBritton) May 30, 2019

We all know that this is an issue, but as it turns out, in doing some digging with Nick at First Pitch Arizona, it seems his slight reversion is closely related to his injury. We’ll come back to this.

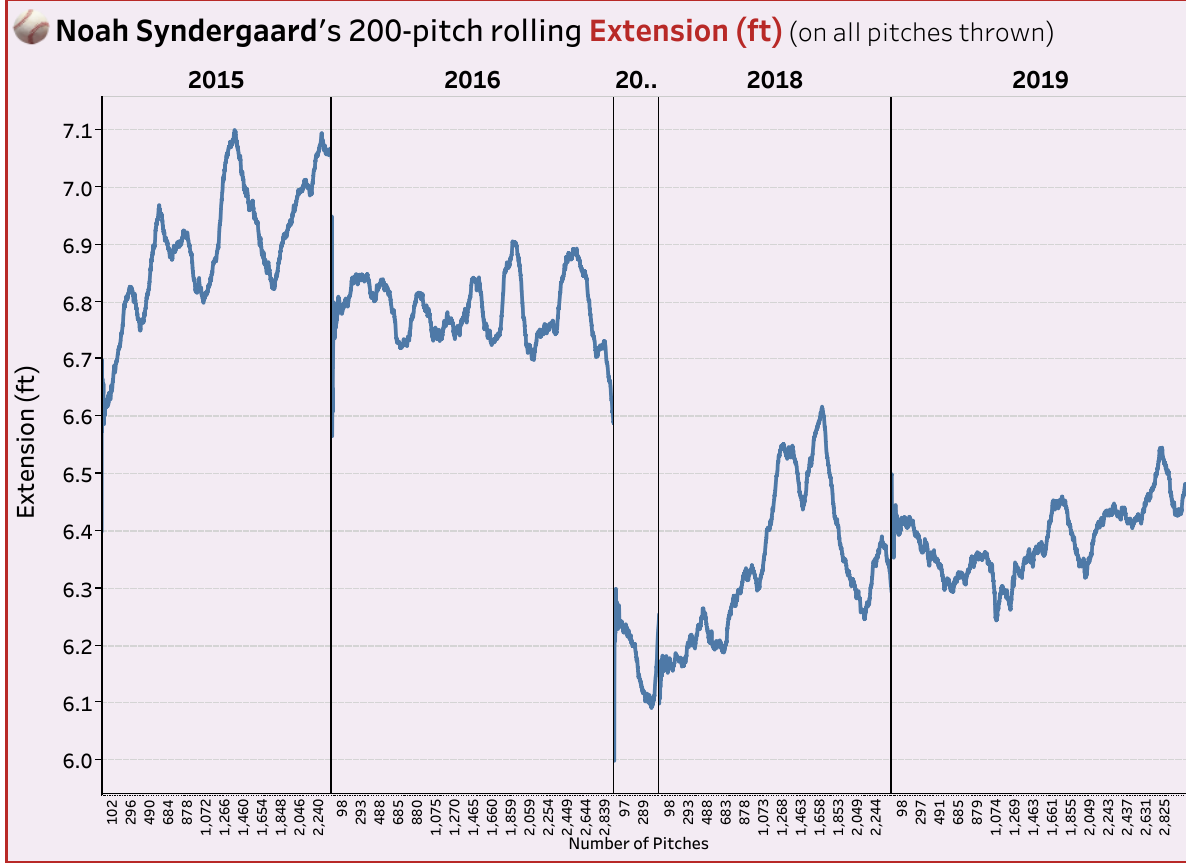

Syndergaard’s 200-pitch rolling extension, courtesy of Alex Chamberlain’s database:

There are a few things here. First, Syndergaard’s extension has dropped significantly. Second, though, is his decline in extension began at the very end of 2016 and persisted at the beginning of 2017. This may suggest that this isn’t directly related to injury, but it could also be that this drop in extension was a precursor to his injury—either due to a change in mechanics, or a sign that an injury was on the horizon.

Regardless of the reason, we can see that Syndergaard had extension, and then he had less extension. This sets up something of a domino effect.

Syndergaard’s four-seam and sinker velocity, before and after his torn lat injury:

| Velocity | Perceived velocity | |

|---|---|---|

| 2015-2017 (SI) | 98.1 | 98.66 |

| 2018-2019 (SI) | 97.4 | 97.68 |

| 2015-2017 (FF) | 98.2 | 98.80 |

| 2018-2019 (FF) | 97.7 | 97.01 |

By velocity, both of his fastballs lost half a tick (or more) of velocity. By perceived velocity, though, he lost an entire tick off his sinker, and nearly two from his four-seam fastball. Having two fastballs that average 97.68 and 97.01 (as perceived by the hitter) is something most pitchers would do anything for, but for Syndergaard, it’s a pretty healthy decrease in perceived velocity, and it seems like it’s affected him. But this is just one piece of the puzzle.

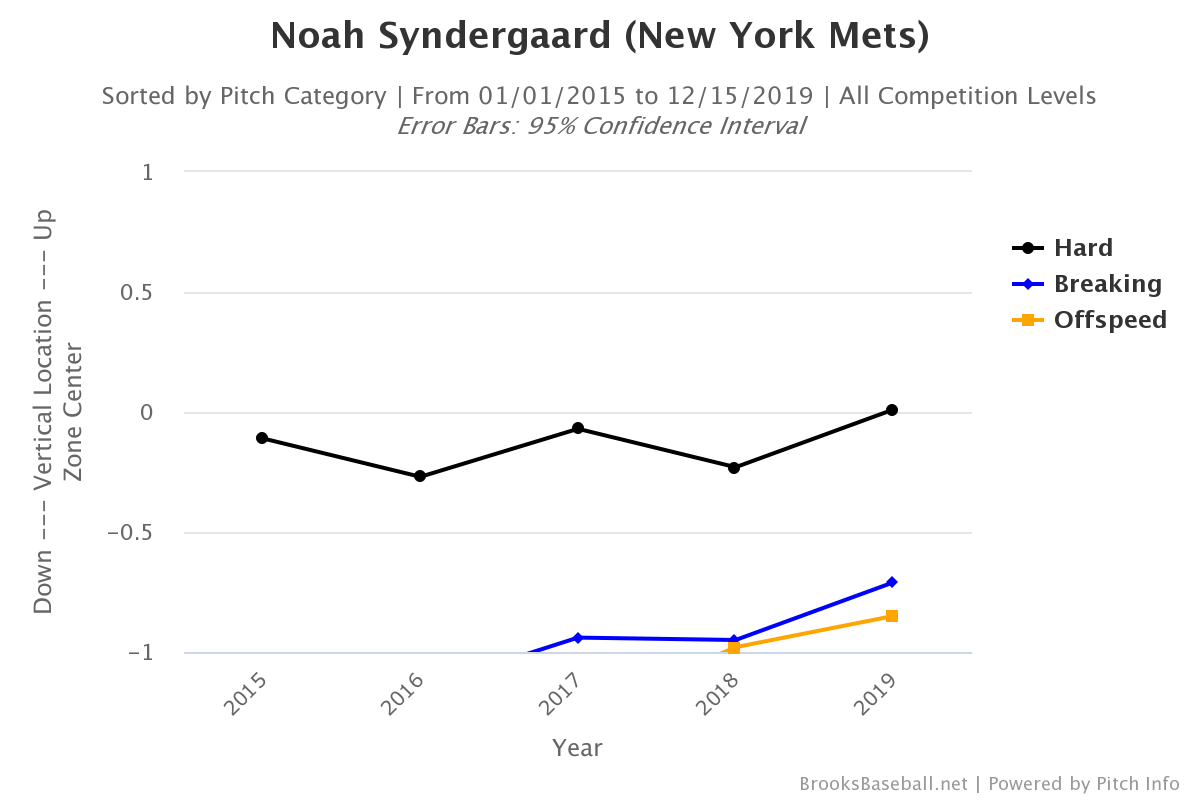

Theoretically, if Syndergaard is getting less extension, it’s likely that he isn’t finishing to stay on top of the ball and keep it low and beneath the zone. Whether he’s short-arming it or just not sitting into his delivery enough is unclear, but he’s getting less extension, and it’s correlated with the following changes in average vertical pitch location:

To avoid superfluousness, I grouped the pitches together by pitch category. As you can see, in 2016, his fastballs are slightly below the vertical-middle of the zone, with his breaking and offspeed pitches located so low that they are out of the graphic. Starting in 2017—when his extension issues mostly began—his breaking pitches rise vertically into the graphic, and then his offspeed pitches join the party in 2018. As Nick and I discussed, there seems to be a mechanical basis for this, but regardless of the reason for it, it’s happening, and that’s what matters. We can’t count on Syndergaard throwing four-seams elevated in the zone, because history says it’s unlikely to happen any time soon. What we can hope for, though—because he’s done it!—is that he’s placing sliders, curveballs, and changeups below the zone. This is especially important with his slider, though, because it is such a vertical pitch. He can let it drift glove-side, but keeping it down and out of the zone is the key.

Let’s see how that has played out. Because 2017 was a partial year, and in 2019 Syndergaard lost the feel of both of his breaking pitches, I feel it is most pertinent to compare his 2016 and 2018 and omit 2019 from our analysis for now. In 2018, he still had a wipeout slider (albeit not as effective), but there were a couple of key differences. As previously mentioned, Syndergaard isn’t burying pitches as well, but he also has leaned on his sinker much more in the past three years in favor of his four-seam fastball, as well as increase his changeup usage.

His detailed zone chart in 2016 versus 2018:

Between the two years, there is overlap, but the biggest differences are that he is neither pitching to the bottom of the zone as well, nor is he throwing arm-side as often. Instead, he’s thrown to his glove side with greater frequency. The difference at the bottom of the zone is a reduction from 323 pitches in that zone to 216—that’s a dramatic decrease. He also had about 100 fewer pitches to his arm side, too. That’s one way to look at it, more broadly.

Let’s take a look by pitch type, between 2016 and 2018:

I wouldn’t blame you if you found this graphic overwhelming. If you look individually, you will see lower breaking and offspeed pitches, as well as a change in fastball frequencies, and thus location. If you look more broadly, I see a shift from an up-and-down approach to an increasingly in-and-out, or horizontal, approach.

Here’s another chart, then, this time pitch type by location:

As I see it, overall, his pitches below the zone are less concentrated than in 2016. That is perhaps due to his aforementioned extension issues, but it could also be the nature of switching from a four-seam-slider approach to a sinker-slider approach. While the former is a vertical pairing, the latter is more of a horizontal pairing (although not a true east-west combination, due to his vertical slider). This means that the nature of his approach should have changed some in terms of location, but, to me, it doesn’t entirely explain why all of his pitches have crept up vertically in the zone. Thus, it’s difficult to say with absolute certainty why his approach has shifted since his repertoire change and extension woes are conflated within the same time period.

Regardless of the explanation for why Syndergaard has changed, there are components from 2016 that he is missing dearly. The extension helps all of his pitches play up, but the easiest changes that Syndergaard can make right now are alterations to his repertoire.

Syndergaard has five—count ’em, five!—pitches that he can command, so while he has the luxury of throwing high-90s fastballs, he doesn’t need to throw 60% fastballs. I’d like to see him switch to his four-seam fastball as his main weapon, while upping his slider to 25-30% while continuing to throw his changeup and curveball with frequency, because they’re underrated, borderline Money Pitches. He doesn’t need to drop his sinker, because it’s still a good pitch with purpose—he can use it arm-side to jam lefties and run off the plate against lefties—but it’s his worse pitch by swinging-strike percentage and contact percentage by far, but also by wOBA and xwOBA. Ideally, he’d drop it down to something like 20% and use it in hitters’ counts when he needs a ground ball.

A side effect of all of this is that Syndergaard has just flat out been pitching to more hittable areas. Again, just looking at 2016 and 2018, we can take a look at Baseball Savant’s attack zones. In two-strike counts, Syndergaard ranked in the 91st percentile (of all pitchers from 2015 to 2019) in total pitches in the shadow and chase portions of the zone with 70.3% in 2016. In 2018, which was still quite a solid year, Syndergaard dropped to 66.5%, which may sound subtle, but it ranks in the 58th percentile. For perspective, that’s like dropping from Tyler Mahle, Masahiro Tanaka, and David Price—all of whom have great command—to Sandy Alcantara, Reynaldo Lopez, and Sonny Gray (the not-good 2018 version!).

As a result, more pitches are going to the heart of the zone—Syndergaard went from a 21.3% heart percentage in two-strike counts in 2016 (71st percentile) to a 25.0% heart percentage (92nd percentile). Syndergaard is better suited than most pitchers to pitch in the heart of the zone, but this isn’t a favorable change for any pitcher, regardless of his velocity and stuff.

To an extent, 2019 was something of a lost season for Syndergaard since he was missing his slider due to the changed properties of the juiced ball. For this reason, I’m incredibly skeptical that he has permanently lost his slider and is now a lesser pitcher. And, in any case, as is, Noah Syndergaard is 27 years old and—without the feel for his breaking pitches—just put up a top-25 FIP-. Clearly, he’ll never need to pitch optimally to be a great starting pitcher, but if he does, we know that he has the tools to be among the absolute best. His defense deserves some of the blame for his BABIP woes—the New York Mets ranked second-worst in DRS and seventh-worst in UZR—but he could certainly help them out by tweaking his pitch mix, and thus putting himself at the mercy of the BABIP gods less often than he is now.

Photo by Dustin Bradford/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Michael Packard

Great read Michael – thanks! I didn’t realize Thor was getting less extension after his injury. That is interesting. His poor defensive support along with his league-leading opponent SBs definitely hurt him. But DeGrom has the same supporting cast with very low hits/9 (although much of that may be attributed to DeGrom’s higher K rate). And, while DeGrom does allow quite a few stolen bases, he doesn’t give up nearly as many as Thor. So, the catcher isn’t entirely to blame. Hopefully, “Thundergod” gets his extension and feel for the ball back, improves his ability to hold runners and becomes (returns to) the dominant pitcher everyone expects.

Regarding his sinker, you said “he can use it arm-side to jam lefties and run off the plate against lefties.” Did you mean “to jam righties?”

Appreciate it! Yeah, I think that has to do with deGrom getting more whiff and Syndergaard inducing so many ground balls. I’m hoping Thor gets back to form too.

And yes! I noticed that typo but haven’t gotten around to fixing it. Thanks for mentioning that.