I don’t think anyone could much consider 2020 a success (if you do, let’s switch places!), but if a Detroit Tigers fan momentarily gave themselves a mental break from the world at large, they’d probably be pretty happy with their 2020 season so far. The Tigers stand 16-16 entering play on Monday, good for just fourth place in a packed AL Central, but a far cry from the 100+ loss campaigns of the past two seasons.

Perhaps more important than the wins and losses, excitement has also returned to Comerica Park in the form of top pitching prospects Casey Mize and Tarik Skubal. Much to the chagrin of our hypothetical Tigers fan, it’s been a choppy transition to the majors for the two aces-in-training. Given pandemic circumstances, it would be cold and distasteful to be particularly critical or overly concerned with their lackluster performance. That isn’t the point here.

This article came about as a failed experiment to find out to whom, if anyone, Skubal and his unique arsenal might be compared. Even so, this is our first look at the publicly available data on Skubal, and it’s always fascinating to find how a top prospect compares to the reports we’ve been getting on them for years. Let’s take a dive under the hood!

Anatomy of a Pitching Prospect

As I said, the results haven’t been great so far. Skubal earned his first MLB victory on Saturday thanks to five innings of three-hit, two-run ball, walking none but striking out just two along the way. Prior to that, he lasted just 4.1 innings in total over his first two starts, giving up five runs in the meantime. On the bright side, he’s walked just 4.8% of the hitters he’s faced through those three starts. Preseason reports on his control, however, were decidedly mixed. Keith Law of the Athletic praised it and MLB.com’s Jonathan Mayo graded it an above-average 55, while Fangraphs’ Eric Longenhagen gave his command a 35 present value and 45 future value.

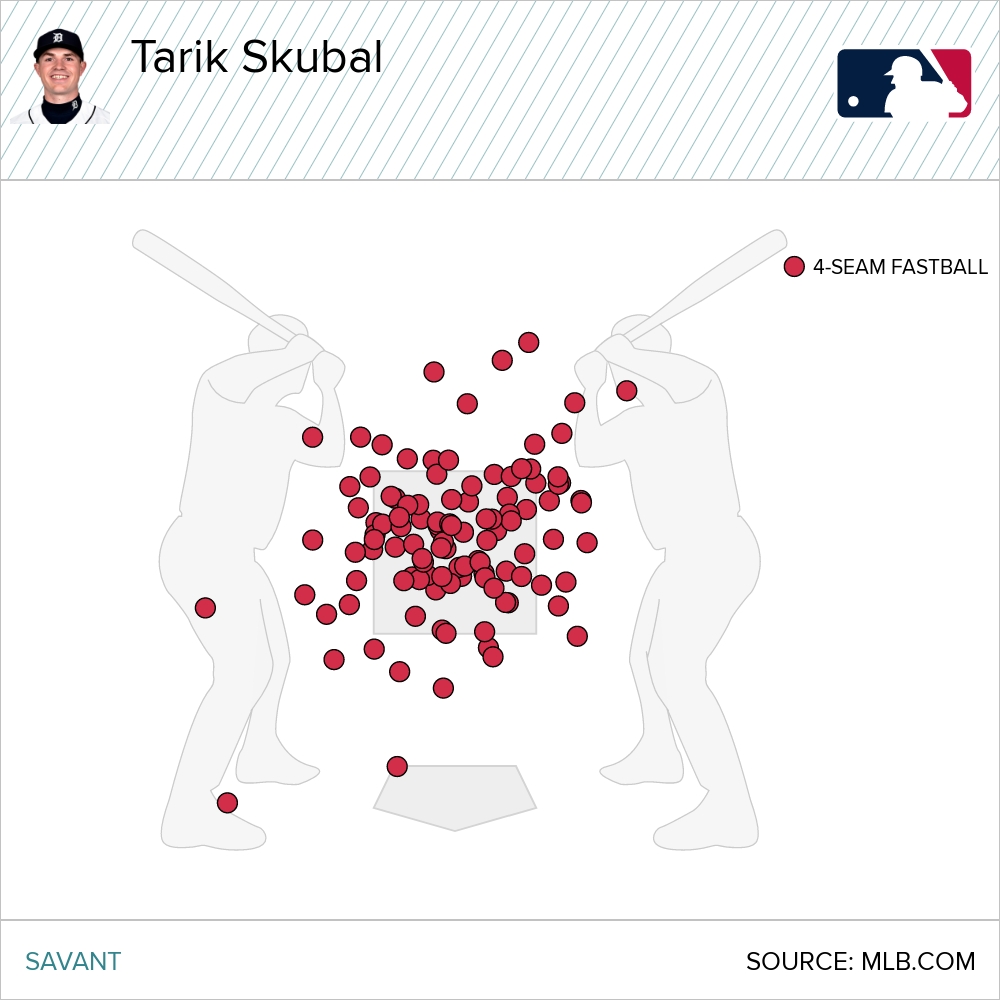

Even so, Skubal hasn’t had much difficulty putting the ball in the zone thus far, running a zone rate (53%) more than 5% above league average. This might seem like a good thing, but unfortunately hitters have not been fooled, batting him around for a .649 slugging percentage and whopping 41.9% hard hit rate, meaning nearly half of the batted balls against him have been at least 95 mph. When you look at his fastball locations, you’ll probably realize why finding the zone that much isn’t necessarily a good thing:

That is a horrifying number of fastballs right down the middle. This is instructive of the difference between control and command. Having some idea of where the ball is going is typically a prerequisite for being a valid major league starter. To be a good starter, though, you need to do more than just put the ball in the zone. That subtle difference between control and command, between just getting it over the plate and actually putting it where you want to, is often enough the difference between an All-Star and a washout.

The early returns on both the data and the eye test say that Skubal has control, but the command is sorely wanting. The idea that he might eventually refine that command is pretty exciting, because as you’re about to see and may already know, he’s got some pretty unique characteristics that could turn him into a pretty special pitcher if he can throw the ball with precision.

Searching For Secondaries

Disagreement over control/command aside, Skubal has more or less resembled the pitcher described in most prospect reports, with a few noticeable tweaks. He’s thrown his four-seamer 58% of the time, so as was anticipated, he hasn’t tried to rely on it to the same extent he did in the minors last year, when it was upwards of 70% of his offerings. That, however, brings us to the Catch-22 currently engulfing the Tigers hurler: While Skubal’s fastball is quite interesting and should be a high-usage pitch, it’s impossible to get away with throwing it 70% of the time, but his three secondaries simply have yet to be effective against major league hitters.

He’s favored the slider over his changeup and curveball as his primary secondary, so to speak, throwing it about 20% of the time overall, bumping that up to 30% when the count reaches two strikes. The results so far haven’t been catastrophic, but they come with more red flags than a windy day on Lake Erie, notching just three strikeouts and drawing whiffs on a well-below average 28.6% of swings.

That’s not to say it doesn’t have potential. Sliders have more different shapes and sizes than Legos, and Skubal’s is almost completely vertical, averaging a very solid 38.2 inches of drop with a minuscule 2.6 inches of horizontal break. When he does command the ball well on a pitch-by pitch level, the vertical separation between the fastball and slide make for a deadly combo (please bear with me as I use you all as guinea pigs for my nascent pitch trail overlay skills):

It seems that ultimately, at least for this questionable-as-ever season, Skubal will need to adjust to living fastball-slider in the major leagues, with all three secondary pitches being urgent works in progress. The curveball and changeup are below average in movement and spin; the former is little more than a show-me pitch to steal a strike now and then, the latter has been hit an average of 97.5 mph the four times it’s been put into play. Fastball-slider is all he’s got, and unfortunately, he ain’t got much of a slider yet. That four-seamer has carried him this far— let’s see what’s to it.

Four-Seam Frenzy

Just as some numbers inside some boxes and with no other context, Skubal looks to have one of the leagues better fastballs, with traits highly coveted by many of today’s front offices. Longenhagen succinctly described it as “equal parts velocity, ride, and tough-to-square angle,” and while we’ll get into that last part in a minute, the public data we’ve gotten so far more or less confirms the first two:

| Velo (MPH) | Spin (RPM) | Active Spin | V-Mov (Inches) | H-Mov (Inches) | Zone Rate | Whiff% | Zone-Whiff | HardHit% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skubal | 95 | 2444 | 90% | 14 | 10.8 | 59.7% | 21.7% | 23.4% | 45.5% |

| MLB Percentile | 75 | 83 | 68 | 47 | 90 | 84 | 67 | 74 | 61 |

| LHP Percentile | 91 | 86 | 66 | 54 | 86 | 79 | 67 | 74 | 63 |

(Source: Baseball Savant)

I don’t know why they would be, but reports were not lying about the velocity. Averaging 95 mph on the dot, Skubal’s four-seamer is hard by any standard, but rarefied territory coming from the left side: among lefty starters this season, only Blake Snell, Yusei Kikuchi (!!) and Jesús Luzardo are throwing harder on average, and only Snell, James Paxton, and Julio Urias broke 95 in 2019.

The definition of what “ride” on a fastball means is a bit up in the air, but there’s undoubtedly something funky about the way this one moves. The 83rd percentile spin is quite good even for his velocity, but despite a modestly above average 90% active spin rate (meaning 90% of his faster-than-average spin contributes to movement), it only generates average rise, with almost the exact same amount of drop as the average fastball with similar velocity and release.

There are a couple reasons that the tepid ride might not matter. The most prominent is that it’s highly unusual for a fastball to have normal, average rise, and still manage to grab a full 11 inches of horizontal movement. In fact, the only four-seamers with less vertical movement (remember, with a “rising” four-seamer, less movement is better) and more horizontal movement belong to Gerrit Cole (whoa) and Tyler Mahle (uh?). These unusual characteristics are part of why despite throwing a whopping 37% of his fastballs over what Statcast defines as the heart of the plate, it’s still drawn a quite solid 25% in-zone whiff rate, nearly 5% above league average.

Right Angles

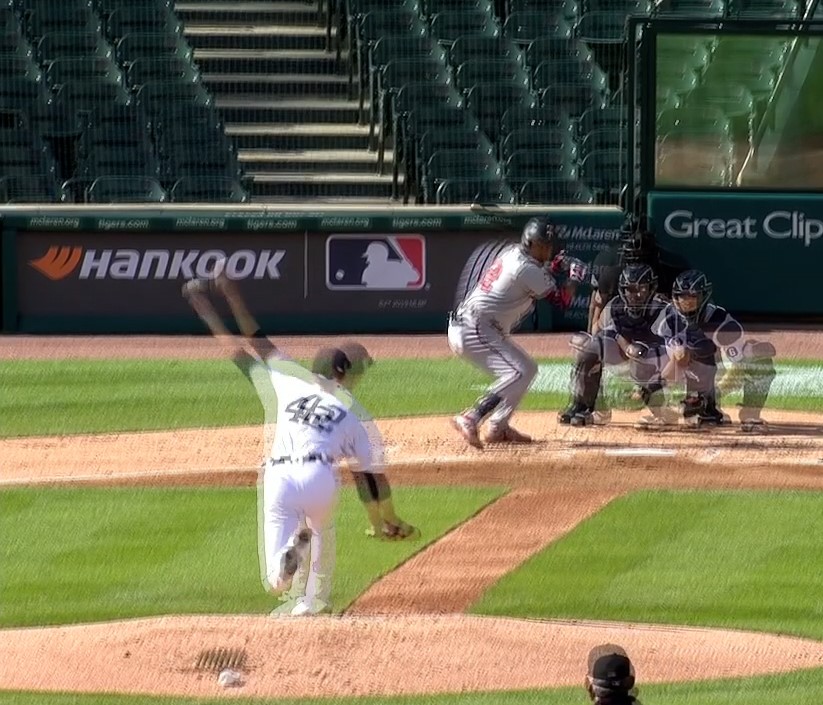

All of that stuff is worth watching before we even get to the “tough-to-square angle” that caused so much ruckus among amateur evaluators. Deception can be tough to address analytically, because it’s often visually dependent and doesn’t necessarily mean the same thing pitcher to pitcher. Let’s slow down one another good pitch of his, sans trail, and see what we can see:

It’s definitely not the craziest windup out there, but it’s not quite run-of-the-mill, either. It’s not super hard to see why his command is lacking. Noticeable to me is the slight degree of cross-body arm action that can sometimes be tough to repeat consistently. It’s certain not impossible — ask Jake Arrieta — but it does make things difficult without superb body control. For a little reference, let’s put him next to a couple other big, fireballing lefties. The goal here isn’t to compare their mechanics in and of themselves, but to see how they operate at particular points in their deliveries. Here’s Skubal, James Paxton, and Blake Snell, frozen with their weight fully on their backside, just before transferring energy forward into the pitch:

Note: Snell’s image is from 2019 and Paxton’s 2018; I consider it pretty important to have a constant location and camera angle when making visual comparisons.

Here, we can begin to understand why this fastball is anecdotally so hard to pick up. Most pitchers show the ball to the hitters at some point in their windup, but Skubal simply doesn’t, shooting his arm straight back and keeping the ball hidden behind his body almost up until release. At 95 mph with good spin, that’s going to play.

Unfortunately, it’s still going to be limited unless he can refine the command. Snell is a fine reference point not because of his control, which is subpar, but because he has a fairly generic windup with fairly clean mechanics. Here, Snell is nicely compact and balanced at when he starts to push his weight forward. Paxton and Skubal, meanwhile, are considerably more violent and herky-jerky in their deliveries. Like Skubal, Paxton has a bit of crossfire to his motion, but notice how linear his shoulders are at the point of rotation, forming almost a straight line from the tip of his glove hand to the ball. This isn’t to say that Skubal needs to start emulating Paxton, but rather to show how Paxton manages to stay on-line and efficient throughout his delivery in a way Skubal doesn’t. Now, check out the trio’s body position just as their front foot hits the ground and their hips begin to uncoil:

On the generic end of things, we can see in part how Snell manages to pump 97 mph with a Gumby build — just look at how his front hip is almost all the way rotated, while his chest is still pointed directly at first base, or even a bit towards second, generating plenty of torque when he does open up his torso. Meanwhile, despite employing the same closed-front-foot stride as Skubal, Paxton manages to get his shoulders in line and pointed at the plate as he hits his front-leg block. It’s difficult to tell exactly where Skubal’s front shoulder is point thanks to the camera position, but his back shoulder clearly hasn’t gotten the memo yet.

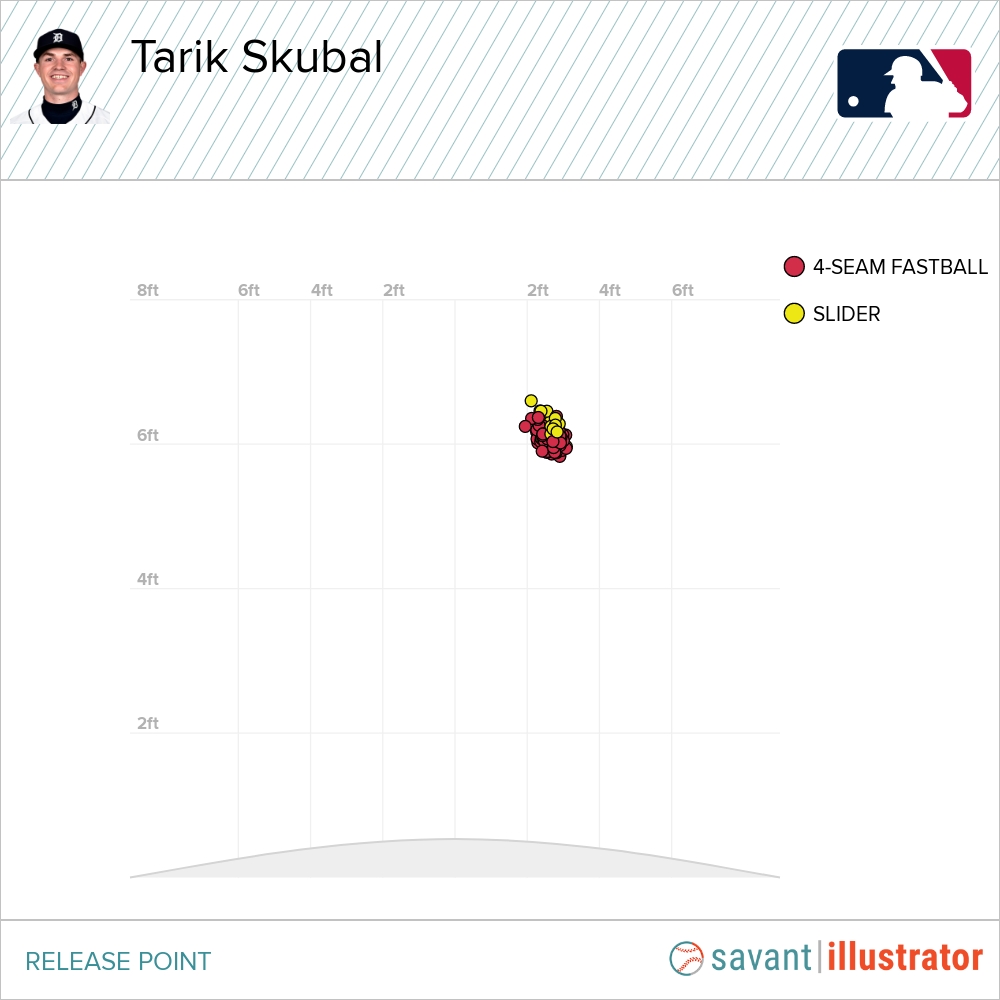

This isn’t a backbreaking detail — none of these are — but consistency is paramount, both in pitching motions and in swings. So long as his extremities are moving more separately than together, it’s going to be difficult to have a tight release point and improve that command to All-Star levels. The fastball-slider combo we just talked about has potential, but it’s still going to be limited so long as hitters can pick up on this kind of separation:

The Good and the Weird

So that’s some of the bad stuff, but that’s not really what I wanted to talk about. The release point chart is a good jump-off point for the last, and perhaps most interesting, abnormality in this kid. I said earlier there were a couple reasons that just getting average rise on his fastball might not matter. The horizontal movement and ball-hiding is a part of it, but spin is only a fraction of the game.

Skubal’s arm angle is actually even funkier than it looks on video. Some of what we call deception is hiding the ball, and some is simply throwing it from a place that almost nobody else does. Here are the most extreme fastball release points in baseball among lefties —essentially, whose fastball is coming farthest from the side and highest over the top:

| Rank | Player | H-Release (feet) | V-Release (feet) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sean Manaea | 3.63 | 5.35 |

| 2 | Jake Diekman | 3.48 | 5.8 |

| 3 | Grant Dayton | 3.32 | 5.65 |

| 4 | Josh Hader | 3.32 | 5.2 |

| 5 | Tommy Milone | 3.27 | 6.09 |

| 6 | Andrew Heaney | 3.03 | 5.26 |

| 7 | Tarik Skubal | 2.98 | 6.26 |

| 8 | Madison Bumgarner | 2.92 | 5.76 |

| 9 | Brent Suter | 2.84 | 6.13 |

| 10 | Paul Fry | 2.7 | 5.57 |

| Rank | Player | H-Release (feet) | V-Release (feet) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sean Newcomb | 1.88 | 6.62 |

| 2 | John Means | 0.83 | 6.54 |

| 3 | Blake Snell | 1.71 | 6.53 |

| 4 | Patrick Corbin | 2.22 | 6.45 |

| 5 | Patrick Sandoval | 0.95 | 6.44 |

| 6 | Drew Pomeranz | 2.36 | 6.31 |

| 7 | Tyler Matzek | 2.01 | 6.29 |

| 8 | Tyler Anderson | 1.78 | 6.29 |

| 9 | Tarik Skubal | 2.98 | 6.26 |

| 10 | Clayton Kershaw | 1.43 | 6.22 |

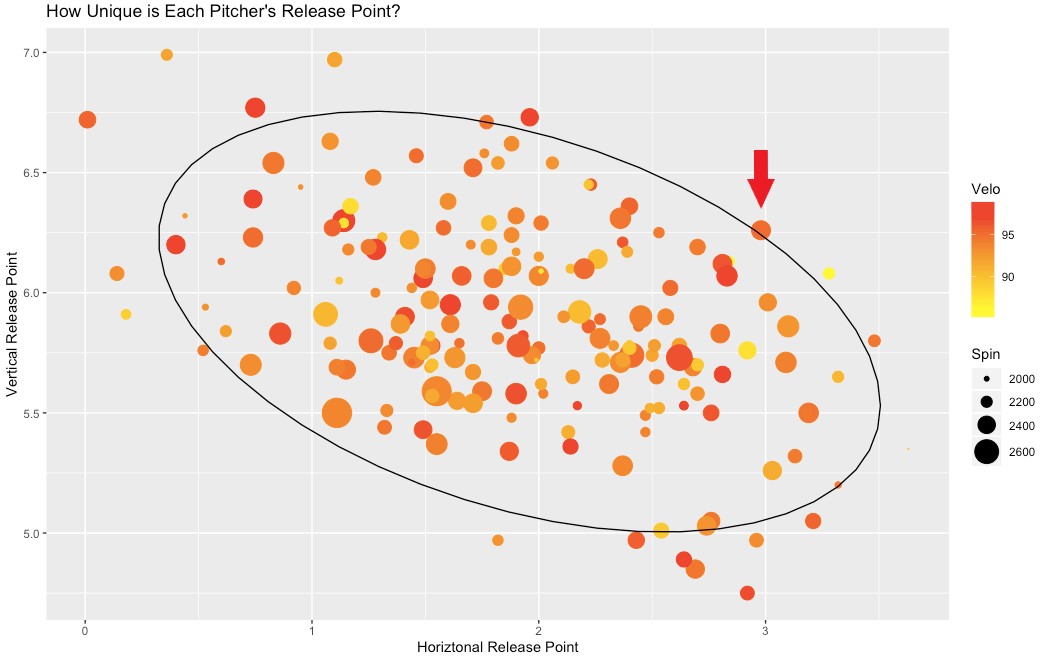

If that’s hard to visualize, think of it this way: Skubal releases his fastball as far to the side as fellow crossfire artist Madison Bumgarner, but also as high in the sky as Clayton Kershaw. That seems like an unusual combination! Just how unusual? We can use something called multivariate outlier detection to help find out. Multivariate outlier detection can help us visualize exactly how unusual a given pair of values is relative to the whole set. When looking at a single variable — horizontal release point, for example — it’s easy enough to figure out whether a value is technically an outlier or not. It’s easy enough that we rarely have to talk about it in mathematical terms. If a player has one of the five highest release points in a sample of 51, we probably don’t need the standard deviation to figure out how unusual it is.

So why go to the trouble of doing this for Skubal when it’s relatively clear to the naked eye that what he does is far from the norm? Truth be told, there might not be. When I came to my friend and resident data wiz Esteban for help on this piece — he’s responsible for all the math and visualizing you’re about to see, go follow him on Twitter — the idea was to create a multivariate similarity score similar to the ones used on Baseball Savant. The real question we were asking was, exactly how unusual is Skubal’s combination of velo, spin, and arm slot? And can we put a number on it?

Unfortunately, math is hard, and we’re still working on getting a nearest-neighbors algorithm that will tell us exactly how far removed from the rest of the pack Skubal is. But we can still use MOD to help show us how out-there the fastball goes. A pair of values might be far from their means, but that doesn’t mean they necessarily defy logic — they’re just to one extreme or the other. MOD can tells us when something is defying norms to the point of not making sense. So without further ado, here’s a plot of horizontal and vertical release points on all qualified four-seamers this year, with other visual aids to denote spin and velocity:

(Source: Esteban Rivera (@esteerivera42))

As you can probably figure out, the arrow is Skubal. The ellipse is what bounds the “cloud” of normally distributed data, meaning that everything on or outside that ellipse is a true outlier. We used absolute values to normalize for handedness to prevent the means from being unnaturally dragged towards zero. The logical justification bears itself out: we can see that the large majority of pitches are released somewhere between 5.5 and 6.25 feet off the ground, and anywhere from 1 to 2.5 feet to the side of the rubber.

Obviously, that’s a pretty wide level of variance, because there are lot of different pitchers throwing from a lot of different release points, and we’re talking about matters of inches, hardly visible to the untrained eye from 60 feet 6 inches away. Anything falling outside the ellipse is liable to throw a hitter for a loop solely by virtue of how infrequently they see anything like it.

Even among the outliers, there’s little quite like Skubal. The points near the bottom with under five feet of height on their release are guys like Aaron Nola, Edwin Diaz, and Craig Kimbrel, who lack top-tier spin on their fastballs but get super low to the ground with a ton of arm-side run on their ball. That really extreme point all the way up in the top left? That’s James Karinchak, who comes so wildly over the top that he’s actually the only right-hander with a negative average horizontal release point, which is WILD. Some of the other statistical outliers are relatively mundane. Tommy Milone, Jorge Alcala, and Sean Manaea apparently have pretty extreme release points, but you wouldn’t consider that to be a part of their game. On the other hand, some of them track very well logically. You don’t have to watch much of Josh Hader, Jake Diekman, or Pete Fairbanks to realize that they’re a little unorthodox.

When velocity and spin get added to the equation, Skubal has even fewer legitimate comps. His nearest neighbors on the chart are Milone and Brent Suter, both of whom throw so soft that you can hardly even see their points on the graph. The only players remotely in the area that can match his velocity and spin are Tanner Rainey, Keynan Middleton, and Spencer Howard, all of whom are right-handers with straightforward, non-deceptive deliveries. It doesn’t look super crazy from a center field camera well, but to a hitters’ eye, a high-spin fastball exploding at 95 mph from that high up and that far to the side is a nightmare to track — if it’s in the right spot.

Looking Ahead

Skubal was able to control his fastball well enough that minor league hitters simply didn’t stand a chance. And as we saw, it’s still getting plenty of whiffs inside the strike zone, even without knowing much where in the strike zone it’s going to go. Now we partly know why — even in the majors, hitters are going to see very few fastballs with the same attributes as this one. The eye test hasn’t been super kind so far, but it would be patently unfair to make any kind of final judgment of his command after just three starts. There’s plenty of time to make adjustments.

Now that we have a pretty good idea of how this fabled fastball actually works, we can dream on what it might do if or when the command does improve. It’s already a more-than-viable pitch as it is — and underlying metrics aside, five innings of three-hit ball is a real accomplishment — and it’s safe to say it has the potential to be every bit as deadly as the reports said it might be.

Unless the curveball or change takes a big step up, however, Skubal still seems likely to go only as far as the fastball-slider combination will take him. The trope of needing three pitches to be a viable big league starter is growing more stale by the year, but even if he’s one of those rare pitchers who can get away with throwing a four-seamer 60% of the time, we’re currently seeing the limits of his upside if he can’t learn to be fine enough to harness it.

Even if he doesn’t pan out, the stuff is still an electric multi-inning reliever starter kit. Whether he can put it together or now, the scouting reports sure weren’t lying. This isn’t your everyday, high-level pitching prospect. It might not be pretty for the time being, but it’s well worth keeping an eye on.

Featured image by Justin Paradis (@FreshMeatComm on Twitter)

Wow Zach – one of the best articles I’ve read in a while. Excellent work!

Appreciate it!