Baseball is perpetually in an existential crisis.

Fans and journalists have been angsting about the future of baseball almost since the time where baseball didn’t even have a past. Baseball is always dying, according to some. Whether it’s attendance, television, free agency, style of play, pace of play, or whatever other issue you can recall, it will beg some to ask the question: how can this continue? Is baseball in danger of simply evaporating?

It’s been a pretty slow news week as far as negotiations go, so let’s go look at some history. The advent of free agency seems particularly relevant at the moment. 1969 is a pretty long time ago, but it’s quite simple and easy to dive into some newspaper archives and see what was being said at the time. Why 1969? Because the moment that we occupy right now has perhaps its primary genesis in that year, when Curt Flood came to the decision to file a one million dollar anti-trust lawsuit against Major League Baseball in what was to that point the most pointed attempt to strike down the infamous Reserve Clause.

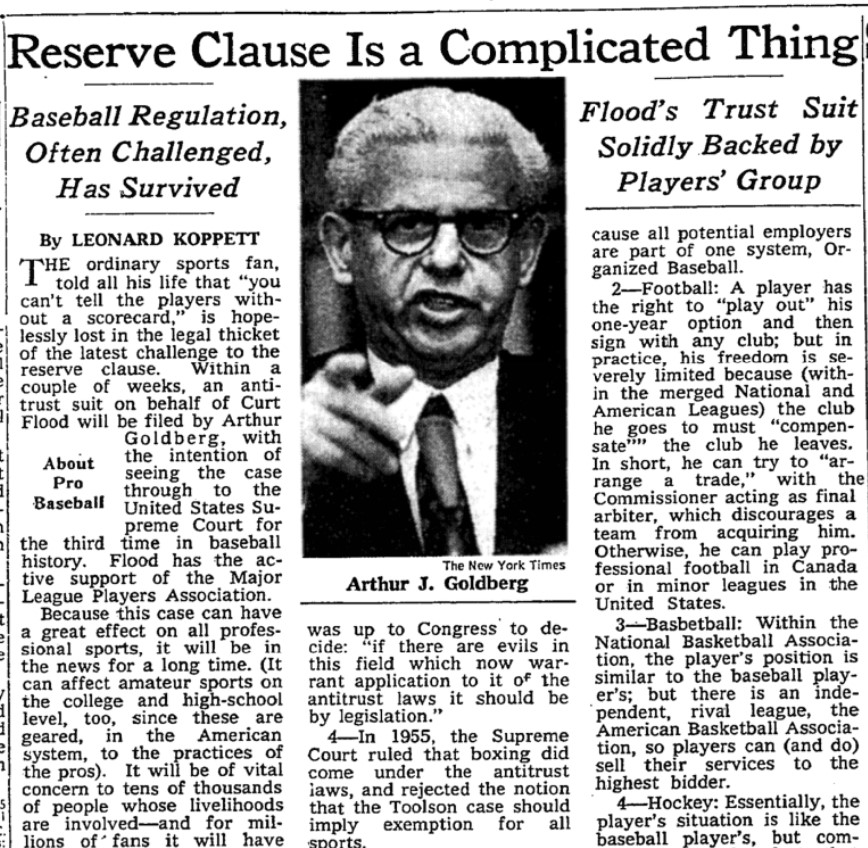

New York Times, January 4th, 1970

Flood is much more relevant in contemporary conversations than he ever seems to get credit for, but he ought to be particularly relevant at this time. The state of affairs that led to Flood’s challenge has a few similarities to our contemporary status quo even without the analogs between years of historically significant social re-orderings and upheavals that precipitated both 1970 and 2021. In the baseball sphere, there was unprecedented growth. Eight games were added to the schedule in 1961, and by the end of the decade, eight expansion teams had entered the league. Baseball on television and all related financial benefits was in its infancy; and by 1970, 20 years of stable attendance after World War II had begun to give way to a slow but steady forty-year upward trend.

Baseball’s success was undeniable. But just like in the present day, where multi-billionaires operating companies also valued in the billions try to convince us that they aren’t making much money, league executives at the time contended that Major League Baseball would literally cease to exist if the old methods were not preserved:

New York Times, January 16th, 1970

Plot twist: professional baseball did not cease to exist without the reserve clause. Even five years later, when it was clear that the reserve clause was on its last legs after Peter Seitz’s now-famous arbitration decision, the league side of the equation didn’t ease up on the hysteria at the prospect of being forced to reduce their levels of exploitation:

New York Times, December 24th, 1975

The vocabulary and excuse-making used by the league and ownership sides have hardly changed in a half-century. Neither have their negotiating tactics. In spite of the binding nature of the Seitz decision — that is, quite literally, the definition of arbitration — the league wasted no time filing a lawsuit in a last-ditch effort to stem the tide of free agency and blatantly renege on the deal they had made with the nascent MLB Players’ Association:

New York Times, December 25th, 1975

This is all meant as a reminder that as long as labor fights have existed in baseball, the owners have never given an inch: the players have had to fight for everything they’ve gotten. The owners have never played fair because the idea of fairness is anathema to an economic philosophy predicated on an endless quest to find (and appropriate) surplus value. One could also cite plenty of newspaper examples with similar sentiments to the above from the 1994 and 1981 strikes, or the late-1980s collusion scandal, the latter two of which generated plenty of support for the players and their union.

So as much as we’ve become used to the word “unprecedented” over the past two years, the owners are slinging the same mud they’ve been picking up since day one. This is just a new battle in an old fight. Why are we seeing history repeat itself so distressingly?

Since the upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s, ownership’s primary (broad) strategy of pushing back on progress has been to make mountains out of molehills and refuse to give an inch unless dragged to the edge. Unfortunately, it has been an almost universally successful strategy, building tremendous amounts of inertia within the current system while simultaneously demonizing players who advocate for radical change — how many words have been written about the negative perception of players that developed during and following the 1994 strike? That double-edged sword helped set the table for the current lockout through its contribution to a series of increasingly disadvantageous post-strike CBAs that have consolidated ownership gains to the point that the disparity simply cannot be ignored any longer.

Media Check-In

We’re seeing in real-time one of the primary ways that owners were able to keep this historical cycle churning for so long. Last week, I wrote at length on how owners and league executives use high-exposure media figures to subtly sway the public to their side and point of view under the guise of neutrality. The rise of this trend helps explain how we got to where we are today. One major difference between now and the 1970s is that owners are (mostly) smart enough to stop spouting off in ways that make them look as malevolently miserly as they actually are. Now, through the internet-age phenomenon of access journalism and the scoop economy, they’ve successfully leveraged fans’ hunger for information as a way to quietly insert their agenda and narratives into mainstream public discourse.

Take the 2014 Jeff Passan column that resurfaced recently opining quite negatively on the effort of a group led by White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf to block Manfred’s election as commissioner in favor of former Red Sox executive Tom Werner:

There’s being wrong, and there’s being wrong. Those two paragraphs don’t reflect the entirety of the story, and it’s been accurately pointed out that a Reinsdorf-backed commissioner would have been equally as destructive, if not more so. Still, the takeaway is that Passan badly misread the nature of Manfred’s character — his sources clearly misled him, and it was to Manfred’s benefit. Full stop. Much of the lead-in to today involves a broad failure by writers and analysts to speak the truth about Manfred and the ownership class until it was too late. Passan himself has deferred to another 2016 column as evidence of his critical foresight on the matter, but it still misses the point. The terms of this relationship were always clear. As the article demonstrates, the exploitative conditions that finally began to boil over in 2020 were evident from the moment the 2016 CBA (which Passan termed “fascinating”) was signed. There’s no excuse for not sounding alarm bells before the tumult of 2020 forced the issue.

Plenty of good journalists spending time on the player side have been raising red flags for years. This lockout was not inevitable, but it became a fait accompli in some part because the media figures with the widest reach have been too indebted to their sources to bring critical attention to how the league has ceaselessly operated with bad faith in recent years. The league has indicated time and time again that its bargaining strategy involves making barely-serious, sometimes not-even-formal offers in an effort to stall and ultimately push the players’ backs against the wall. Only the owners benefit by refusing to turn up the pressure until the last possible moment, and it’s worth considering how the dynamic between scoop merchants and league sources helps facilitate that lack of accountability.

The same forces behind the docility that got us here are continuing to use those channels in an attempt to sway public opinion and pressure the players into taking a subpar deal before games are set to be canceled. It’s already well in progress. You may have already seen the proposal for new CBA terms that Jayson Stark put out into the world. No matter what you think of the idea, it does at the very least appear (on the surface) to be original:

ICYMI: If MLB really wants to stop tanking I can help. Here’s the plan:

Reverse the draft order

So teams with best records that miss the playoffs would pick first

How to pick the next Griffey: Try

How not to pick the next Griffey: TankHere’s more https://t.co/gAEaecyNwN

— Jayson Stark (@jaysonst) December 11, 2021

Inside the article (subscription required), Stark insists that this idea is fully his own. Let’s take him at his word. It still doesn’t make the way he presents his idea any less tainted by pro-ownership bias. But as he would probably point out, the article begins with a quotation from MLPBA executive subcommittee member Andrew Miller! He also recently hosted Miller on his podcast!

That seems fair enough. In all likelihood, Stark thinks he’s writing from a position of neutrality. But the sources he uses in the article tell a different story. Following the introductory quote from Miller, the people quoted or paraphrased are:

- “People”

- A player agent

- “People in front offices”

- A league executive

- A league executive

- A league executive

- Athletic reporter Evan Drellich

- “Sources briefed on negotiations”

- The MLPBA

- A player agent

- A league executive

- A league executive

- A league executive

There is no argument here. Even if Stark presents his piece in a blissfully ignorant state of unbias, the feedback and information being given to the public is heavily slanted towards management perspectives by definition of league sources outnumbering player sources at least seven to two (at minimum). It might not be anything conscious on Stark’s part, but it sure is reflective of where most of his information is coming from. In that same vein, it’s also reflective of how seriously we should take his suggestions.

Stark wasn’t even the first writer at the Athletic to lob a haughty set of suggestions to the mob. Let’s check in on Ken Rosenthal, who as we referenced last week has some history of dubiously claiming ownership of the proposals made in his columns:

Won’t somebody please think of the low-revenue clubs?

Reminder: there is no such thing as a low-revenue club. There are low-payroll clubs, but a low-payroll is not the same thing as low-revenue. The latter is a reality, the former is a choice. The reality we inhabit is not one in which a sub-$80 million payroll can be justified by low revenue. This is settled math. Next question.

Rosenthal’s article is quite lengthy, and this article is already quite lengthy, so we can get the substance of it in some bullet points. Under the so-called Rosenthal plan:

- The revenue-sharing formula remains the same, but with a mandate that the money must be spent on the major league payroll. This is presented mere words after clarifying that he is not proposing a salary floor. There’s a brief mention that the union may have some issues with the fact that ancillary income (i.e., money from other things around the stadium owned by the team) isn’t accounted for in the revenue sharing formula. That might seem fine, but “neighborhood development” has been repeatedly demonstrated to be a financial mechanism for diverting funds from the players to ownership pockets. Seems like an issue worth exploring more! Instead, we have a masterclass in buried ledes.

- We see a modified version of the union’s age-based free agency proposal, but with the added bonus of implementing a franchise tag-lite — excuse me, a franchise icon subsidy — to help those seemingly abundant low-revenue clubs keep their star players. Let’s pretend for just a moment that the idea of league subsidizing extensions for teams too cheap to give them out themselves isn’t the entirely asinine suggestion that it is. We must also point out that never in the history of baseball has allowing the league to dictate “fair market value” worked out to the benefit of the players. After the way the last five offseasons have played out, we’re supposed to believe that giving teams more free money will incentivize them to start spending? I was born at night, but it wasn’t last night. Being spoon-fed ideas by league sources would almost be less embarrassing than putting this out on one’s own accord.

- The minimum salary is increased by roughly $200,000, and Super Two eligibility is expanded. Otherwise, arbitration remains the same. Truly revolutionary stuff.

- Beyond the absurdity of the First-Year Draft being presented as the most important issue for improving competitive balance, the only comment I have on the proposal therein is that I hope to someday love someone as much as Rosenthal seems to love the words “low-revenue.” The phrase appears no fewer than twelve times throughout the column.

- Expanded playoffs: “pretty much the owners’ plan.” I like it when he saves me the trouble.

These are the opinions that are being presented to us as reasonable before even the slightest inkling of negotiation content has begun to leak. When more concrete details of proposals and counter-proposals begin to see the sun, these same familiar names will be the ones taking it upon themselves to make both sides seem equally reasonable and unreasonable. But history has shown time and time again that ownership definitions of reasonable are nowhere close to ours. Perhaps more importantly, we don’t have to take Jayson Stark or Ken Rosenthal’s ideas of reasonable as ours, either.

I’ll conclude this the same way we wrapped up last week: owners are relying on people like you on me to turn on players once the going gets tough. Nonetheless, what’s true at the beginning of the lockout will still be true at the moment games begin to be canceled: the only way the game gets better is for the players to make a lot of meaningful gains. Staying strong in their support in spite of what ESPN might be spitting at you is the only way we all win.

Photo by James Black/Icon Sportswire | Design by Michael Packard (@designsbypack on Twitter @ IG)

“I’ll conclude this the same way we wrapped up last week: owners are relying on people like you on me to turn on players once the going gets tough.”

They’ve succeeded. I hope the reserve clause comes back.