There have been a lot of fantastic articles written about park factors—from Eno Sarris’ 2019 piece on HD/HR rate, to Alex Chamberlain’s extremely informative pitch tableau sheet, to Pitcher List’s own Dan Richards’ park factors articles. One thing I noticed about some park factor pieces, however, is that they don’t always take batted-ball directionality into account. Let me firmly state that this is by no means a slight on any of those pieces—I constantly reference them and believe they should be industry standards—I just thought perhaps there was an interesting opportunity to explore here.

It’s common knowledge in the baseball community that the short porch in Yankee Stadium makes it easier for left-handed hitters to pull homers, but do pull-happy righties have just as much success to left field? What about guys like Alex Bregman who frequently put up big pull-power numbers while lacking in the barrels department; is he a prime regression candidate or just a beneficiary of Minute Maid?

I wanted to know: In which parks does batted-ball directionality matter the most?

To roughly paraphrase Richards’ piece, if you’re going to be looking at park factors, barrels are a good place to start. (For a more in-depth breakdown of barrels, I’d highly suggest checking out Colin Charles and Scott Chu’s Fantasy 101 piece on advanced stats).

| Year | Barreled 1B% | Barreled 2B% | Barreled 3B% | Barreled HR % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2.8% | 16.4% | 2.1% | 59.6% |

| 2018 | 2.4% | 17.9% | 2.4% | 53.7% |

| 2017 | 2.2% | 16.3% | 2.1% | 61.5% |

| 2016 | 2.3% | 18.7% | 2.6% | 56.9% |

| 2015 | 1.9% | 17.9% | 2.8% | 56.3% |

As barrels are a good indicator of power, it would make sense that most barreled balls are home runs. While, on average, about 58% of barrels result in home runs, far more home runs themselves are barreled.

| Year | HR | Barreled HR | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 6776 | 5536 | 81.7% |

| 2018 | 5585 | 4538 | 81.3% |

| 2017 | 6105 | 4869 | 79.8% |

| 2016 | 5610 | 4528 | 80.7% |

| 2015 | 4909 | 3912 | 79.7% |

Oddly enough, it seems that in every year in which barrels have been recorded, the league average for % of HRs that have been barreled is around 81%. As this piece is mostly concerned with directionality though, it’s important to find out where the barreled HRs are mostly going.

| Year | Pull | Straightaway | Oppo |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 55.3% | 29.7% | 15.0% |

| 2018 | 61.4% | 27.3% | 11.2% |

| 2017 | 58.7% | 28.8% | 12.5% |

| 2016 | 61.3% | 27.6% | 11.2% |

| 2015 | 58.9% | 29.1% | 12.0% |

We’ve reached our first conclusion here: Most barreled home runs are hit to the pull side. That seems pretty intuitive. Most hitters want to barrel the ball because it optimizes their power output, and virtually all hitters predominantly pull the ball. Knowing this, I can amend the question I had at the beginning of the piece to be a bit more specific: Where do barreled, pulled home runs matter the most? To put it another way: In which park can you get away with not barreling your home runs to the pull side?

Where Have All the Barrels Gone?

Let’s start by looking at how many pulled home runs were barreled last year by stadium.

| Rank | Venue | All Pulled HR | Pull HR Barrel | % of PBHR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Minute Maid Park | 186 | 125 | 67.2% |

| 2 | GABP | 121 | 82 | 67.8% |

| 3 | Rogers Centre | 167 | 115 | 68.9% |

| 4 | Tropicana Field | 106 | 74 | 69.8% |

| 5 | Fenway Park | 122 | 86 | 70.5% |

| 6 | Citizens Bank Park | 158 | 112 | 70.9% |

| 7 | Coors Field | 150 | 108 | 72.0% |

| 8 | Dodger Stadium | 133 | 99 | 74.4% |

| 9 | PNC Park | 98 | 73 | 74.5% |

| 10 | Oriole Park | 162 | 121 | 74.7% |

| 11 | Yankee Stadium | 141 | 106 | 75.2% |

| 12 | Citi Field | 136 | 104 | 76.5% |

| 13 | Nationals Park | 146 | 112 | 76.7% |

| 14 | Comerica Park | 137 | 106 | 77.4% |

| 15 | Wrigley Field | 107 | 83 | 77.6% |

| 16 | Miller Park | 121 | 94 | 77.7% |

| 17 | Target Field | 157 | 123 | 78.3% |

| 18 | Marlins Park | 111 | 87 | 78.4% |

| 19 | Progressive Field | 130 | 102 | 78.5% |

| 20 | Chase Field | 140 | 111 | 79.3% |

| 21 | Globe Life Park | 141 | 112 | 79.4% |

| 22 | T-Mobile Park | 163 | 130 | 79.8% |

| 23 | Oracle Park | 101 | 81 | 80.2% |

| 24 | Petco Park | 124 | 100 | 80.6% |

| 25 | Guaranteed Rate Fld | 126 | 102 | 81.0% |

| 26 | Oakland Coliseum | 119 | 99 | 83.2% |

| 27 | Angel Stadium | 117 | 98 | 83.8% |

| 28 | SunTrust Park | 122 | 103 | 84.4% |

| 29 | Busch Stadium | 112 | 96 | 85.7% |

| 30 | Kauffman Stadium | 114 | 99 | 86.8% |

In 2019, there were 186 pulled home runs in Minute Maid. Of those 186, 125—or 67%—were barreled. Meaning that you don’t necessarily need to barrel your pulled homers in Minute Maid, whereas if you want to hit pulled home runs in Kauffman, they would likely need to be barreled. At first glance, this makes a lot of sense. Bregman hit 41 HRs last year, and while 78% of them were pulled (20 percentage points above league average), only 54% were barreled (30 percentage points below league average), and just 32% were both pulled and barreled (23 percentage points below league average). This chart lets me know that I might be on the right path to something, but I’m a bit wary of using pure counting stats to determine whether a park is good at turning pulled barrels into HRs. Before I can start to make claims about other parks that stick out, I want to further verify that this data is true. In order to do so, I’ll look into another metric and arguably the best power indicator: wOBAcon and xwOBAcon.

wOBAcon is wOBA (once again Charles/Chu’s article is a helpful refresher on wOBA if needed) when contact is made with the ball. Think of it like BABIP but with HRs added. Much like with wOBA, the higher the wOBAcon, the better. Just as xwOBA gives us a better idea as to what a wOBA should’ve been based on similarly batted balls, xwOBAcon gives us a better idea as to what a wOBAcon should have been. Subtracting one from the other is a quick and easy way to determine how batted balls may have over- or underperformed. I’ll use the next chart to elucidate.

| Rank | Stadium | wOBAcon – xwOBAcon |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Minute Maid Park | 0.845 |

| 2 | GABP | 0.829 |

| 3 | Rogers Centre | 0.791 |

| 4 | Citizens Bank Park | 0.753 |

| 5 | Tropicana Field | 0.74 |

| 6 | Coors Field | 0.739 |

| 7 | Fenway Park | 0.721 |

| 8 | Oriole Park | 0.717 |

| 9 | Yankee Stadium | 0.708 |

| 10 | Dodger Stadium | 0.703 |

| 11 | Citi Field | 0.697 |

| 12 | Wrigley Field | 0.692 |

| 13 | Nationals Park | 0.686 |

| 14 | Progressive Field | 0.685 |

| 15 | Target Field | 0.684 |

| 16 | PNC Park | 0.681 |

| 17 | Comerica Park | 0.68 |

| 18 | Miller Park | 0.676 |

| 19 | Marlins Park | 0.675 |

| 20 | Chase Field | 0.655 |

| 21 | Guaranteed Rate Fld | 0.641 |

| 22 | Petco Park | 0.632 |

| 23 | T-Mobile Park | 0.632 |

| 24 | Angel Stadium | 0.629 |

| 25 | SunTrust Park | 0.627 |

| 26 | Oracle Park | 0.625 |

| 27 | Globe Life Park | 0.615 |

| 28 | Busch Stadium | 0.614 |

| 29 | Kauffman Stadium | 0.589 |

| 30 | Oakland Coliseum | 0.583 |

Minute Maid is at the top of our list. The .845 difference between its wOBAcon and xwOBAcon means that there was almost a 900-point gap between how the pulled HR ball performed and how the pulled HR ball should have performed. The larger the gap between these two metrics, theoretically, the less reliant a hitter would need to be on barrels to have their pulled HR leave the yard. (Now that you have a good understanding of this, I highly suggest checking out Chamberlain’s park factors tableau linked at the top of the piece.) Now let’s see if this correlates to the percentage of home runs that were barreled chart.

It does. Very well. Now that I know these two datasets correlate, I feel a bit more comfortable digging into what they mean. Here are a few takeaways:

- There is no better park for pulled, barreled HRs than Minute Maid. This is great news for Yuli Gurriel and Bregman and any other pulled-fly-ball hitter in Houston.

- Tropicana, usually considered a pitchers park, is actually very good for pulled, barreled fly balls.

- Miller Park becomes a bit more of a toss-up between a pitchers and hitters park.

- It’s very tough to get away with non-barreled, pulled HRs in Oakland.

- Oracle Park, while likely still below average overall for hitters, may not be the worst stadium for pulled, barreled HRs.

- Virtually every park factors article I’ve seen has Fenway listed as a predominately pitchers park. If a hitter is pulling the ball there, they’re either hitting the Green Monster or close to the Pesky Pole. Which highlights an important point…

If we’re going to be looking at directionality, it seems silly to lump everything in together. The beauty of stadiums is that their dimensions are so different, so it almost seems unfair to create a park factor list that treats them as one whole entity. Is Fenway in the top 10 because of the Green Monster, the Pesky Pole, or both? Let’s begin by looking at lefties.

The Impact of Handedness

| Rank | Stadium | % Bar HR LHH | w-xwOBAcon |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yankee Stadium | 60.00% | 0.897 |

| 2 | GABP | 65.50% | 0.857 |

| 3 | Rogers Centre | 68.80% | 0.834 |

| 4 | Minute Maid Park | 71.00% | 0.809 |

| 5 | PNC Park | 64.00% | 0.809 |

| 6 | T-Mobile Park | 70.00% | 0.803 |

| 7 | SunTrust Park | 76.90% | 0.787 |

| 8 | Comerica Park | 71.70% | 0.769 |

| 9 | Coors Field | 73.00% | 0.744 |

| 10 | Chase Field | 68.50% | 0.73 |

| 11 | Citizens Bank Park | 75.40% | 0.713 |

| 12 | Miller Park | 73.30% | 0.711 |

| 13 | Progressive Field | 76.30% | 0.708 |

| 14 | Marlins Park | 73.30% | 0.704 |

| 15 | Angel Stadium | 82.50% | 0.702 |

| 16 | Oriole Park | 77.30% | 0.7 |

| 17 | Busch Stadium | 78.60% | 0.69 |

| 18 | Target Field | 81.80% | 0.668 |

| 19 | Tropicana Field | 78.70% | 0.665 |

| 20 | Nationals Park | 77.20% | 0.66 |

| 21 | Dodger Stadium | 75.40% | 0.654 |

| 22 | Globe Life Park | 78.00% | 0.648 |

| 23 | Citi Field | 75.90% | 0.646 |

| 24 | Fenway Park | 71.70% | 0.634 |

| 25 | Kauffman Stadium | 86.70% | 0.617 |

| 26 | Oakland Coliseum | 85.00% | 0.616 |

| 27 | Guaranteed Rate Fld | 85.10% | 0.607 |

| 28 | Oracle Park | 75.00% | 0.57 |

| 29 | Petco Park | 82.40% | 0.566 |

| 30 | Wrigley Field | 93.90% | 0.511 |

A few things before analyzing: While the r2 between these two is a bit weaker (to see the r2, hover over the trendline) it’s still plenty significant and, for this chart, I sorted by the difference between wOBAcon and xwOBAcon. The table is fully sortable if you’d like to sort by Barreled HR/HR. Now some more takeaways:

- Yankee Stadium is exactly what we though it was: a heaven for lefty hitters who can pull their HRs.

- Fenway Park significantly fell down the list from 7th overall to 24th for LHH.

- Busch Stadium shifts from a complete pitchers park to more of a neutral park for LHH.

- Dodger Stadium looks a lot less power friendly to LHH.

- Hello, PNC Park! Only 64% of HRs were barreled there, which is strange because, while some may call it a pitchers park and others more of a toss-up, it’s certainly never labeled as a hitters park.

While this chart is illuminating, we need to keep in perspective how it compares to the chart that lumped lefties and righties together. For example, Citi Field fell from 11th to 23rd. Yankee Stadium rose from ninth to first, and Fenway plummeted from seventh to 24th. The only explanation for that would be what’s going on with right-handed hitters.

| Rank | Stadium | % Bar HR RHH | w-xwOBAcon |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Minute Maid Park | 65.00% | 0.865 |

| 2 | GABP | 69.70% | 0.806 |

| 3 | Tropicana Field | 62.70% | 0.798 |

| 4 | Citizens Bank Park | 67.70% | 0.782 |

| 5 | Fenway Park | 69.70% | 0.774 |

| 6 | Wrigley Field | 70.30% | 0.773 |

| 7 | Dodger Stadium | 73.40% | 0.755 |

| 8 | Rogers Centre | 69.00% | 0.754 |

| 9 | Citi Field | 76.90% | 0.736 |

| 10 | Coors Field | 71.30% | 0.735 |

| 11 | Oriole Park | 72.90% | 0.728 |

| 12 | Nationals Park | 76.40% | 0.703 |

| 13 | Guaranteed Rate Fld | 78.50% | 0.661 |

| 14 | Petco Park | 80.00% | 0.656 |

| 15 | Marlins Park | 81.80% | 0.654 |

| 16 | Progressive Field | 81.50% | 0.654 |

| 17 | Oracle Park | 82.60% | 0.65 |

| 18 | Miller Park | 82.00% | 0.64 |

| 19 | Comerica Park | 80.20% | 0.637 |

| 20 | Target Field | 78.70% | 0.614 |

| 21 | T-Mobile Park | 83.50% | 0.61 |

| 22 | Chase Field | 86.00% | 0.608 |

| 23 | Kauffman Stadium | 87.00% | 0.57 |

| 24 | Busch Stadium | 90.00% | 0.568 |

| 25 | Globe Life Park | 81.40% | 0.567 |

| 26 | Yankee Stadium | 86.40% | 0.567 |

| 27 | Oakland Coliseum | 82.30% | 0.566 |

| 28 | Angel Stadium | 85.00% | 0.559 |

| 29 | PNC Park | 85.40% | 0.549 |

| 30 | SunTrust Park | 90.00% | 0.507 |

Once again we’ve seen some stadiums shift around, and once again there are a lot of fantastic takeaways:

- This doesn’t pertain to parks but still interesting to note that the r2 here jumped from .68 for LHH to .88 for RHH

- Right handed. Left handed. It doesn’t matter: Minute Maid Park is a great park for hitters

- To answer a question I introduced at the beginning of the piece: Yankee Stadium is far less friendly to pulled HRs for RHH than it is for LHH.

- The same is also true for SunTrust, which goes from 7th on the LHH chart to 30th.

- Wrigley Field shoots up from 30th to 6th.

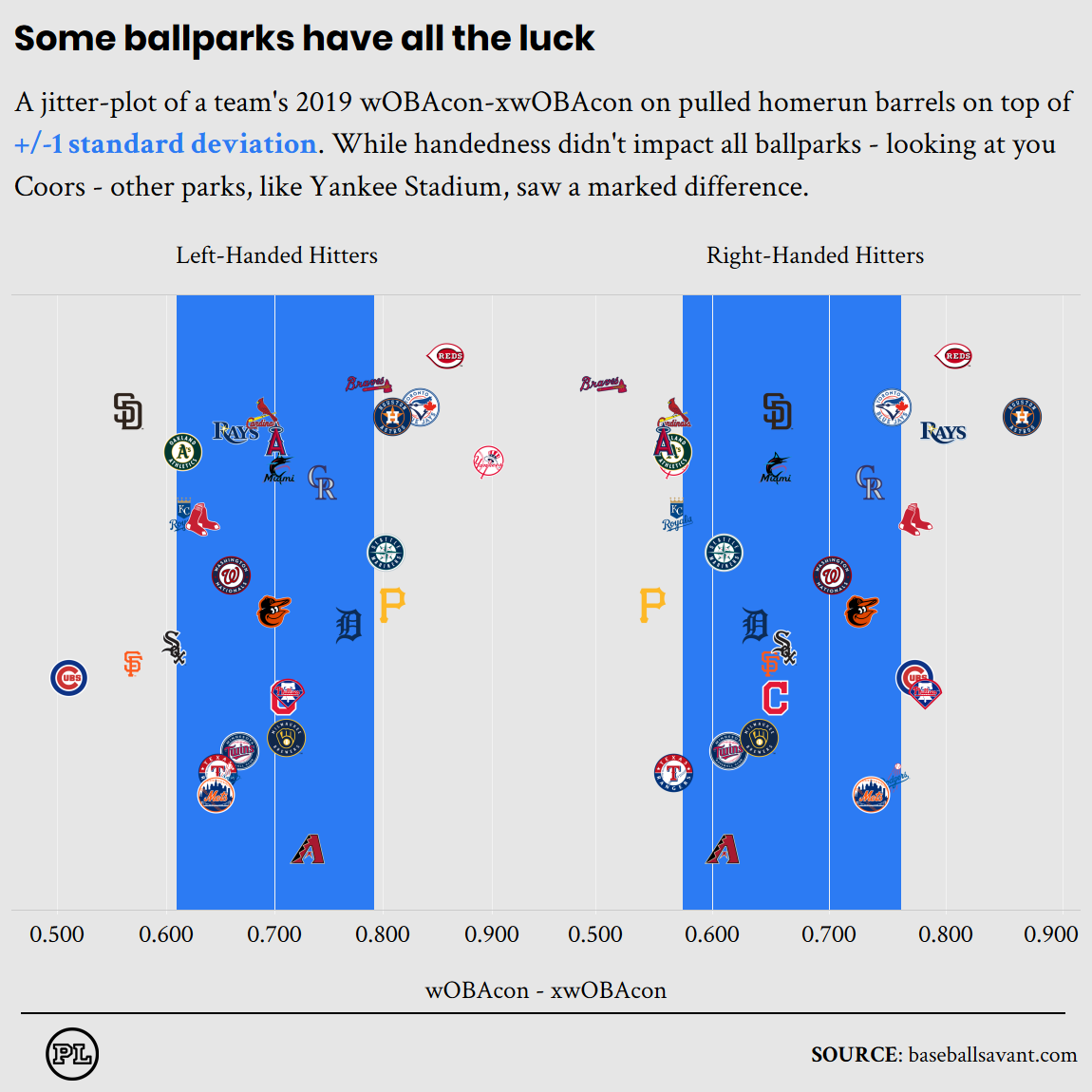

For a bit of a clear look at how parks stacked up against one another by handedness, take a look at this incredibly helpful graphic by Nick Kollauf.

To quote Eno Sarris’ park factors piece, “park factors suck.” There is just so much nuance and noise that can go into them. To see if the data above was just a result of last year’s outcomes, I added two more data sets to my sample: the 2017 and 2018 seasons. I settled on just two more seasons of additional data, as in that period there have been no new ballparks; SunTrust is the most recent (2017).

Adding to the Sample Size

| Stadium | % PullBar HR (19) | % PullBar HR (17-19) | Diff | w-xwoBACON (19) | w-xwoBACON (17-19) | Diff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angel Stadium | 83.80% | 84.20% | -0.40% | 0.629 | 0.6 | 0.029 |

| Busch Stadium | 85.70% | 83.00% | 2.70% | 0.614 | 0.598 | 0.016 |

| Chase Field | 79.30% | 80.40% | -1.10% | 0.655 | 0.614 | 0.041 |

| Citi Field | 76.50% | 76.40% | 0.10% | 0.697 | 0.672 | 0.025 |

| Citizens Bank Park | 70.90% | 73.00% | -2.10% | 0.753 | 0.723 | 0.03 |

| Comerica Park | 77.40% | 76.20% | 1.10% | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0 |

| Coors Field | 72.00% | 71.20% | 0.80% | 0.739 | 0.736 | 0.003 |

| Dodger Stadium | 74.40% | 78.60% | -4.20% | 0.703 | 0.648 | 0.055 |

| Fenway Park | 70.50% | 76.80% | -6.30% | 0.721 | 0.633 | 0.088 |

| GABP | 67.80% | 68.40% | -0.70% | 0.829 | 0.811 | 0.018 |

| Globe Life Park | 79.40% | 77.20% | 2.20% | 0.615 | 0.626 | -0.011 |

| Guaranteed Rate Fld | 81.00% | 74.80% | 6.10% | 0.641 | 0.698 | -0.057 |

| Kauffman Stadium | 86.80% | 83.20% | 3.60% | 0.589 | 0.577 | 0.012 |

| Marlins Park | 78.40% | 77.30% | 1.10% | 0.675 | 0.648 | 0.027 |

| Miller Park | 77.70% | 79.30% | -1.60% | 0.676 | 0.639 | 0.037 |

| Minute Maid Park | 67.20% | 64.40% | 2.80% | 0.845 | 0.874 | -0.029 |

| Nationals Park | 76.70% | 80.60% | -3.90% | 0.686 | 0.621 | 0.065 |

| Oakland Coliseum | 83.20% | 82.80% | 0.40% | 0.583 | 0.584 | -0.001 |

| Oracle Park | 80.20% | 74.90% | 5.30% | 0.625 | 0.699 | -0.074 |

| Oriole Park | 74.70% | 75.10% | -0.40% | 0.717 | 0.7 | 0.017 |

| Petco Park | 80.60% | 76.80% | 3.90% | 0.632 | 0.676 | -0.044 |

| PNC Park | 74.50% | 73.00% | 1.50% | 0.681 | 0.724 | -0.043 |

| Progressive Field | 78.50% | 78.40% | 0.10% | 0.685 | 0.683 | 0.002 |

| Rogers Centre | 68.90% | 70.40% | -1.60% | 0.791 | 0.745 | 0.046 |

| SunTrust Park | 84.40% | 78.50% | 5.90% | 0.627 | 0.668 | -0.041 |

| T-Mobile Park | 79.80% | 76.60% | 3.10% | 0.632 | 0.647 | -0.015 |

| Target Field | 78.30% | 77.70% | 0.60% | 0.684 | 0.623 | 0.061 |

| Tropicana Field | 69.80% | 74.20% | -4.40% | 0.74 | 0.691 | 0.049 |

| Wrigley Field | 77.60% | 76.80% | 0.80% | 0.692 | 0.668 | 0.024 |

| Yankee Stadium | 75.20% | 73.20% | 2.00% | 0.708 | 0.714 | -0.006 |

First things first: Once we increased the sample size, the correlation got stronger, which is always a good sign. With that said, let me give you a quick rundown of what it is exactly we’re looking at here. %PullBar 19 is the amount of HRs that were pulled and barreled in 2019 by park, %PullBar 17-19 is that same metric but for every park between 17-19, with the difference being the former minus the latter. The greater the difference, the more or fewer pulled HRs were barreled. For example, 83.8% of HRs were barreled in 2019 in Angel Stadium and 84.2% of HRs were barreled between 2017 and 2019 for a difference of four-tenths of a point. To the right of that we have the wOBAcon-xwOBACon on HRs by stadium for 2019 and the same data for 2017-2019. The final column is the difference between those two.

I found it really interesting that not that many parks changed too drastically. On average, the difference between pulled barreled HR% in ’17-’19 and ’19 was just 0.58, while the average difference between w-xwOBAcon was .011. Considering the noise that can usually accompany park factors—like fences being moved in our out—and the changes to the ball, I thought there’d be some more variation.

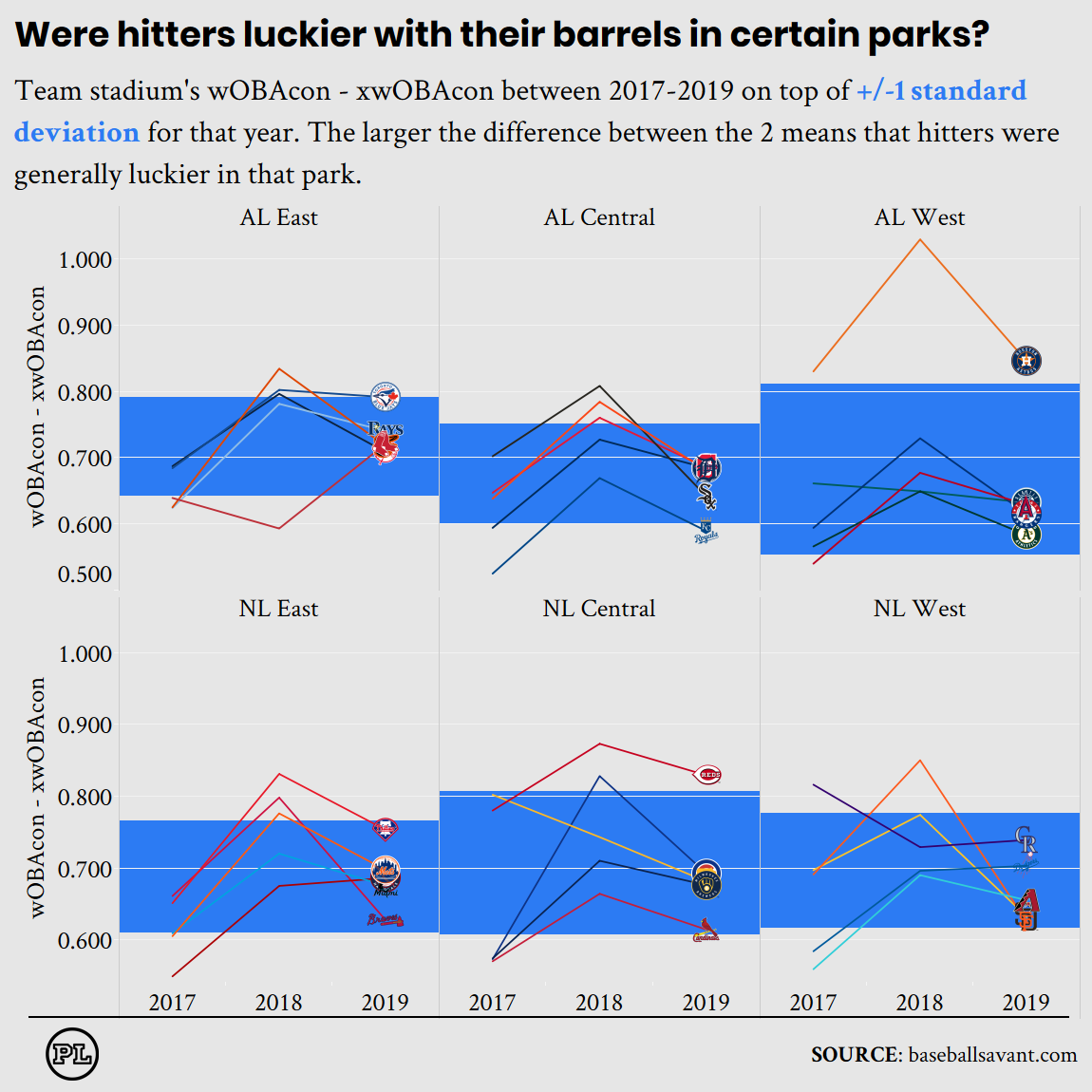

For a divisional perspective, here’s another fantastic graphic created by Kollauf.

Let’s take a look at what happened when we take handedness into account. I’m going to spare you the scatter plots for those and tell you that the r2 for left-handed hitters went from 0.68 to 0.86 while the r2 for right-handed hitters went up from 0.89 to 0.92.

| Stadium | % PullBar HR (19) | % PullBar HR (17-19) | Diff | w-xwoBACON (19) | w-xwoBACON (17-19) | Diff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angel Stadium | 82.50% | 81.50% | 1.00% | 0.702 | 0.653 | 0.049 |

| Busch Stadium | 78.60% | 77.40% | 1.20% | 0.69 | 0.696 | -0.006 |

| Chase Field | 68.50% | 80.30% | -11.80% | 0.73 | 0.618 | 0.112 |

| Citi Field | 75.90% | 78.20% | -2.30% | 0.646 | 0.6 | 0.046 |

| Citizens Bank Park | 75.40% | 74.30% | 1.10% | 0.713 | 0.711 | 0.002 |

| Comerica Park | 71.70% | 73.30% | -1.60% | 0.769 | 0.743 | 0.026 |

| Coors Field | 73.00% | 68.80% | 4.20% | 0.744 | 0.788 | -0.044 |

| Dodger Stadium | 75.40% | 75.90% | -0.50% | 0.654 | 0.693 | -0.039 |

| Fenway Park | 71.70% | 81.30% | -9.60% | 0.634 | 0.55 | 0.084 |

| GABP | 65.50% | 68.40% | -3.00% | 0.857 | 0.821 | 0.036 |

| Globe Life Park | 78.00% | 72.30% | 5.80% | 0.648 | 0.68 | -0.032 |

| Guaranteed Rate Fld | 85.10% | 78.10% | 7.00% | 0.607 | 0.672 | -0.065 |

| Kauffman Stadium | 86.70% | 80.10% | 6.50% | 0.617 | 0.602 | 0.015 |

| Marlins Park | 73.30% | 72.70% | 0.60% | 0.704 | 0.682 | 0.022 |

| Miller Park | 73.30% | 73.90% | -0.50% | 0.711 | 0.685 | 0.026 |

| Minute Maid Park | 71.00% | 67.30% | 3.70% | 0.809 | 0.853 | -0.044 |

| Nationals Park | 77.20% | 82.00% | -4.80% | 0.66 | 0.582 | 0.078 |

| Oakland Coliseum | 85.00% | 83.40% | 1.60% | 0.616 | 0.585 | 0.031 |

| Oracle Park | 75.00% | 75.30% | -0.30% | 0.57 | 0.636 | -0.066 |

| Oriole Park | 77.30% | 75.00% | 2.30% | 0.7 | 0.691 | 0.009 |

| Petco Park | 82.40% | 78.70% | 3.60% | 0.566 | 0.671 | -0.105 |

| PNC Park | 64.00% | 70.40% | -6.40% | 0.809 | 0.751 | 0.058 |

| Progressive Field | 76.30% | 76.50% | -0.20% | 0.708 | 0.714 | -0.006 |

| Rogers Centre | 68.80% | 68.70% | 0.10% | 0.834 | 0.775 | 0.059 |

| SunTrust Park | 76.90% | 72.20% | 4.70% | 0.787 | 0.779 | 0.008 |

| T-Mobile Park | 70.00% | 69.50% | 0.50% | 0.803 | 0.753 | 0.05 |

| Target Field | 81.80% | 78.10% | 3.70% | 0.668 | 0.653 | 0.015 |

| Tropicana Field | 78.70% | 76.40% | 2.30% | 0.665 | 0.681 | -0.016 |

| Wrigley Field | 93.90% | 87.40% | 6.50% | 0.511 | 0.544 | -0.033 |

| Yankee Stadium | 60.00% | 63.10% | -3.10% | 0.897 | 0.892 | 0.005 |

| Stadium | % PullBar HR (19) | % PullBar HR (17-19) | Diff | w-xwoBACON (19) | w-xwoBACON (17-19) | Diff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angel Stadium | 85.00% | 86.10% | -1.10% | 0.559 | 0.562 | -0.003 |

| Busch Stadium | 90.00% | 87.20% | 2.80% | 0.568 | 0.524 | 0.044 |

| Chase Field | 86.00% | 80.50% | 5.50% | 0.608 | 0.61 | -0.002 |

| Citi Field | 76.90% | 75.10% | 1.80% | 0.736 | 0.724 | 0.012 |

| Citizens Bank Park | 67.70% | 72.00% | -4.30% | 0.782 | 0.732 | 0.05 |

| Comerica Park | 80.20% | 77.80% | 2.40% | 0.637 | 0.646 | -0.009 |

| Coors Field | 71.30% | 72.80% | -1.50% | 0.735 | 0.704 | 0.031 |

| Dodger Stadium | 73.40% | 81.00% | -7.60% | 0.755 | 0.609 | 0.146 |

| Fenway Park | 69.70% | 74.50% | -4.70% | 0.774 | 0.676 | 0.098 |

| GABP | 69.70% | 68.50% | 1.20% | 0.806 | 0.802 | 0.004 |

| Globe Life Park | 81.40% | 82.50% | -1.20% | 0.567 | 0.568 | -0.001 |

| Guaranteed Rate Fld | 78.50% | 72.50% | 5.90% | 0.661 | 0.716 | -0.055 |

| Kauffman Stadium | 87.00% | 85.40% | 1.50% | 0.57 | 0.559 | 0.011 |

| Marlins Park | 81.80% | 80.40% | 1.40% | 0.654 | 0.624 | 0.03 |

| Miller Park | 82.00% | 85.00% | -3.10% | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.05 |

| Minute Maid Park | 65.00% | 62.80% | 2.10% | 0.865 | 0.887 | -0.022 |

| Nationals Park | 76.40% | 79.70% | -3.20% | 0.703 | 0.647 | 0.056 |

| Oakland Coliseum | 82.30% | 82.30% | 0.00% | 0.566 | 0.583 | -0.017 |

| Oracle Park | 82.60% | 74.70% | 7.90% | 0.65 | 0.733 | -0.083 |

| Oriole Park | 72.90% | 75.10% | -2.20% | 0.728 | 0.704 | 0.024 |

| Petco Park | 80.00% | 75.90% | 4.10% | 0.656 | 0.679 | -0.023 |

| PNC Park | 85.40% | 75.70% | 9.70% | 0.549 | 0.695 | -0.146 |

| Progressive Field | 81.50% | 81.30% | 0.10% | 0.654 | 0.635 | 0.019 |

| Rogers Centre | 69.00% | 71.50% | -2.50% | 0.754 | 0.727 | 0.027 |

| SunTrust Park | 90.00% | 84.00% | 6.00% | 0.507 | 0.573 | -0.066 |

| T-Mobile Park | 83.50% | 80.80% | 2.70% | 0.61 | 0.585 | 0.025 |

| Target Field | 78.70% | 77.40% | 1.30% | 0.614 | 0.601 | 0.013 |

| Tropicana Field | 62.70% | 72.90% | -10.20% | 0.798 | 0.698 | 0.1 |

| Wrigley Field | 70.30% | 70.50% | -0.20% | 0.773 | 0.743 | 0.03 |

| Yankee Stadium | 86.40% | 81.10% | 5.30% | 0.567 | 0.573 | -0.006 |

Conclusion

Park factors are nuanced. Just as one metric can’t perfectly encapsulate a player; one metric can’t perfectly encapsulate a park. Over the past three years, Oracle Park has been friendlier than I originally thought to a statistically prominent batted-ball profile: pulled, barreled HRs. Fenway isn’t great for lefties but is for righties. Bregman may barrel the ball, but Minute Maid lets us know that might not matter so much. The point isn’t to provide you with one convenient metric to epitomize a park, it’s to provide you nuanced data that will help you better analyze players.

Graphic created by Zach Ennis.

This is a masterpiece. Thanks for this, Alex!

Thank you for reading, Clay!