One of the ways I decide what I want to analyze and write about is by poking around the statistics leaderboards for things that look interesting or unexpected. The leaderboard for offensive production, as measured by wRC+, is filled with many of the names you’d expect – Aaron Judge, Mookie Betts, Freddie Freeman, and so on. Then a few qualify as surprises from pre-season expectations, like Nathaniel Lowe and Yandy Díaz.

As you might expect, these players have hit quite a few homers. Through games played on September 18, nine of the top ten players by wRC+ have hit 20 or more home runs this season. Only Díaz has hit fewer than 20 home runs. Somehow, he’s running a top ten wRC+ with just 9 homers. Contact wizards Jeff McNeil and Luis Arraez are the next most productive players that haven’t hit double-digit homers, at 139 and 133 wRC+.

This seeming oddity piqued my interest. Specifically, how common is it for a player to be at least 40% better than league average with the bat without hitting double-digit pitches into the seats? I don’t know it to be true, but my guess is that it’s quite rare.

I pulled seasonal data for every qualified hitter since 2001. I found there have been five individual, completed seasons where a qualified hitter had a wRC+ greater than or equal to 140 and fewer than ten home runs. But! Four of those five seasons came from the 2020 60-game season. If we discard those on the assumption that those players – Michael Conforto (9 homers), Anthony Rendon (9), Brandon Nimmo (8), and Paul Goldschmidt (6) – likely would have hit double-digit homers in a full 162-game season, then there is only José Reyes’ 2011 campaign (142 wRC+, 7 homers, 126 games) for the New York Mets that meets the criteria.

I extended the search back a little further and found that Reyes’ 2011 is the only instance of this particular combination occurring in a full season since 1992 when Brett Butler (140 wRC+, 3 homers, 157 games) pulled it off for the Dodgers. Going back to 1969, when the pitcher’s mound was lowered, there have been 21 total instances, including five by Wade Boggs and two by Tony Gwynn in the 1980s, and three by Rod Carew in the 1970s.

You might not intuitively put Yandy Díaz in this company – that’s a pretty incredible group of players – and he might hit another homer in the last couple of weeks and make my little exercise with arbitrary thresholds moot. But, that’s not the point. The points are, that Díaz has is a production profile that is unique in the game today and he’s having a put-it-all-together kind of season for the Rays in 2022.

Origin Story

On the surface, the arc of Díaz’s development is one that fits what’s become a somewhat common mold over the past decade or so. As an older prospect in the Cleveland organization, thanks to his defection from Cuba, he was often lauded for his bat-to-ball contact skills and outstanding plate discipline but was never regarded as a top-of-the-list prospect. One of the things holding Díaz back was 30-grade power that was not projected to improve much. Nonetheless, Díaz displayed a mature, professional approach at the plate at every level.

In 2017, when Díaz peaked at 10th among Cleveland’s prospects, he was described this way by MLB Pipeline: “A disciplined right-handed hitter who never tries to do too much and knows how to control the zone… He lets the ball travel deep into the zone and makes good contact with a compact swing and flat path through the zone that produces line drives across the whole field, albeit with little over-the-fence power.”

Despite that “little over-the-fence” power comment and the fact that Díaz never hit more than 9 homers in a season in the minors, he flashed well above average exit velocities in his limited big league action with Cleveland in 2017 and 2018. It wasn’t so much that he lacked power (or strength), it was that his swing was geared toward generating line drive and ground ball contact.

Shortly after he debuted with Cleveland in early 2017, articles were popping up about the possible swing changes Díaz could make to lift and pull the ball more. Despite the clear desire for some adjustment, across 2017 and 2018 with Cleveland, he averaged very low launch angles (0.5 degrees and 4.4 degrees launch angles), tiny 10.7% and 12.2% flyball rates, and hit the ball up the middle or to the opposite field about 80% of the time while posting roughly league average cumulative offensive production (.283/.361/.366 (97 wRC+)) with just one homer and a 22.6% extra-base hit rate.

When Tampa Bay traded Jake Bauers and $5M cash as part of a three-team deal that included Seattle acquiring Díaz from Cleveland after the 2018 season, it was apparent they were betting they could achieve the swing tweaks Cleveland hadn’t and unlock his power by helping him pull the ball in the air more.

Díaz in Tampa Bay

In 2019, that forecast looked good, as Díaz began the season pulling the ball and hitting it in the air more often. Ultimately, he posted a new career-high launch angle (5.7 degrees), fly ball (17.2%), and pull rates (28.0%), and ranked in the 90th percentile for average exit velocity and 94th percentile for maximum exit velocity. It is worth noting that those batted ball profile numbers, while significantly improved for him, were modest in the broader context of the game. Díaz did not suddenly become a pull-happy flyball hitter. But, opening up his pull side and getting the ball off the ground a little more resulted in a strong .267/.340/.476 (118 wRC+) triple-slash line and he popped a career-best (at any level) 35 extra-base hits (43.7%) and 14 homers in just 79 games. That he accomplished that while maintaining strong walk (10.1%) and strikeout rates (17.6%) in line with what he’d shown in Cleveland was an added bonus.

Then came 2020, which was a weird season for a lot of reasons. A hamstring injury caused Díaz to miss about a month of playing time and hampered his ability to find his timing. As a result, those pulled fly balls from 2019 were again infrequent and he ran a career-high 66.0% ground ball rate and hit 45.4% of his batted balls to the opposite field. Just 8.2% of his total batted balls were fly balls, which our Chad Young found was the lowest rate of any hitter in a season with at least 100 PA since 2012.

Díaz’s overall average launch angle was -7.9 degrees (yes, negative) and declined further to -19.2 degrees when he hit the ball to his pull side. Not only did he hit lots more worm burners, but he also did not hit them as hard (perhaps due in some measure to the injury). His average exit velocity was a career-low 88.3-mph (40th percentile) and his hard hit rate (30.9%) was about 30% less than it had been before, resulting in only five total extra-base hits (14.3%) and two homers.

Despite those seemingly negative changes, Díaz delivered his most productive offensive campaign yet – .307/.428/.386 (139 wRC+) – in part because he walked (16.7%) a lot more than he struck out (12.3%) and because he benefitted from a .347 batting average on balls in play.

The dramatic change in approach may be attributable to Díaz trying to find his footing after the injury, but also may have been in response to adjustments in the way pitchers attacked him with fewer pitches in the strike zone (42.9% zone rate) and fewer offerings up in the zone (47.8% located low). Díaz, ever the professional hitter, was content to take his walks and shoot low pitches the other way.

Last season, Díaz said his goal was “to be the Yandy of 2019.” To that end, pitchers obliged with more strikes (49.2% zone rate) and more elevated pitches (44.1% low), and Díaz got back to his pull swing (31.3%). The fly balls (22.7%) also returned (and then some). His average exit velocity rebounded slightly (89.9-mph, 64th percentile), resulting in 34 total extra-base hits (28.5%) and 13 homers in a career-high 134 games. He also ran the second-best walk (12.8%) and strikeout rates (15.7%) of his career. But, his BABIP luck flipped (.287) and his seasonal line was only about 11% above league average .256/.353/.387 (111 wRC+).

Putting It All Together

Since he’s been with Tampa Bay, Díaz has had a season where he’s pulled the ball and hit it in the air with elite contact authority and very good plate discipline measures. He’s had a season where he hit the ball on the ground and the opposite way, but with elite plate discipline (walking more than striking out) and great batted-ball fortune. He’s had a season where he pulled and lifted the ball with excellent plate discipline, but without the top-of-the-scale exit velocity and with unfortunate batted ball luck. All the elements for a breakout season have been there at various points, but never at the same time. He’s been searching for a season where they all came together.

That’s exactly what 2022 has been:

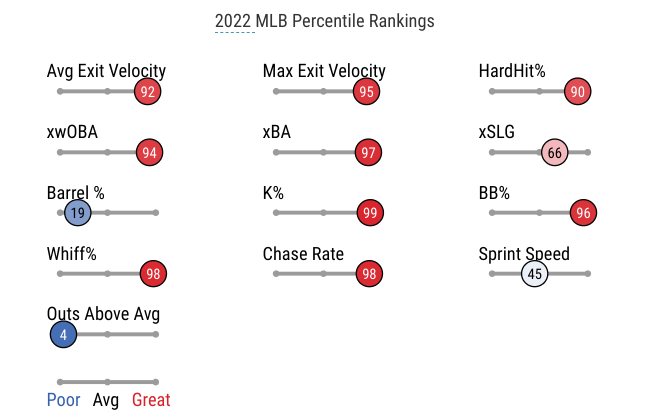

Yandy Diaz Statcast Summary

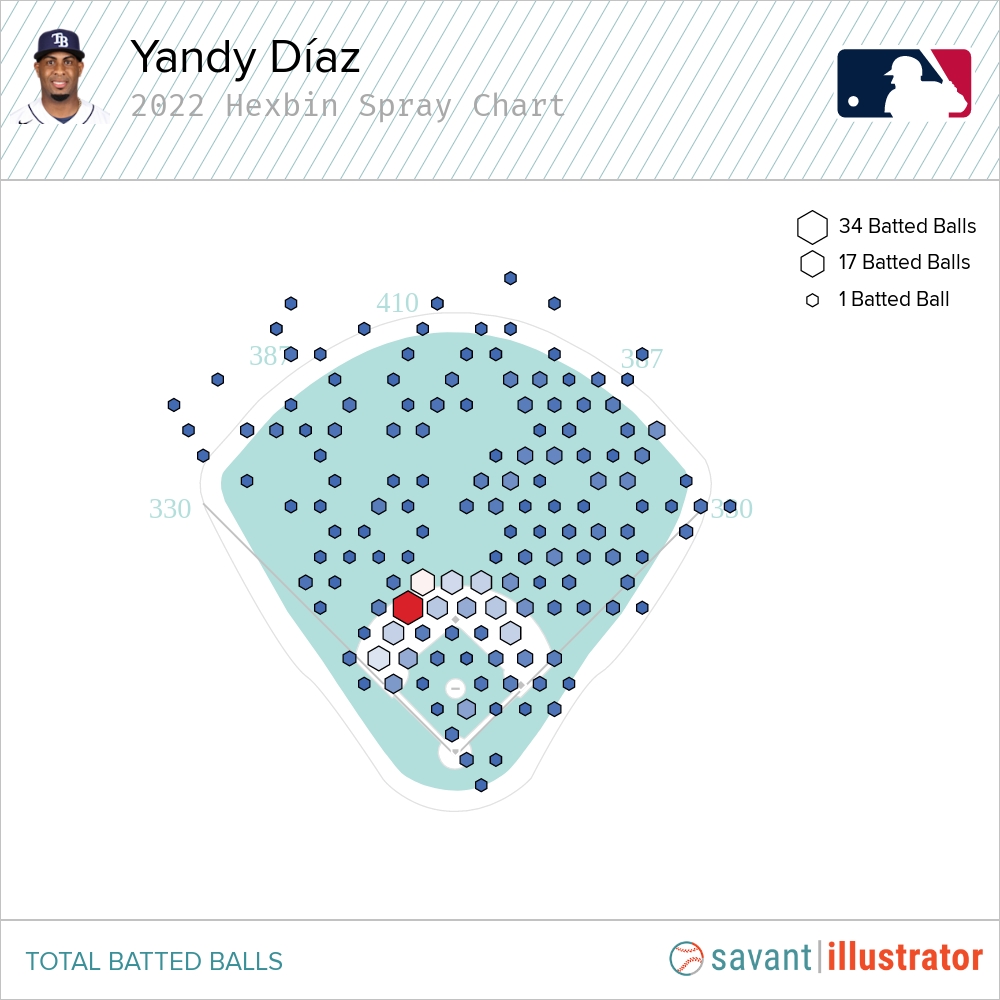

This season, Díaz is once again making hard contact on par with the best in the game, as you can see from the markers above. Moreover, he’s gotten his average launch angle up to a career-best 7.8-degrees and is running a career-low 49.8% ground ball rate. He’s pulled the ball 29.3% of the time, the second-highest mark of his career, and his .320 BABIP has more or less normalized near his .311 career average. He’s walked (14.0%) a lot more than he’s struck out (10.3%).

As a result of this confluence, Díaz has hit a fantastic .295/.401/.423 (147 wRC+) and bopped a career-high 41 extra-base hits (30.5%, 32 doubles, 9 homers) in 132 games. On top of all that, by almost any measure you want to use, his actual numbers are in-line with his expected marks derived from underlying and peripheral stats. He’s put it all together and it looks legit.

Unlike other stories about players learning to pull and elevate, Díaz hasn’t turned into a full-fledged three-true outcomes-oriented, fly-ball bopper. That’s not his game. He’s still that disciplined, does not try to do too much hitter who is exceedingly productive through a selective, hit it (hard) to all-fields where it’s pitched approach:

In that way, he’s similar to those contact and plate discipline legends I listed earlier. He’s still going to pull grounders and hit liners up the middle and the opposite way most often. But he’s also evolved and developed as a hitter, learning how to take fuller advantage when he gets opportunities to drive the ball for extra bases. That makes him fit right in with other hitters in today’s modern, data-driven optimization game.

That all makes Yandy Díaz an outlier blend of old school and new, and this season he’s finally put all the pieces together to produce with the best the game has to offer.

Photo by Anastasia Taioglou/Unsplash | Featured Image by Ethan Kaplan (@DJFreddie10 on Twitter and @EthanMKaplanImages on Instagram)

Interesting article John. How do you think his profile will work with the no shift rule next year? Will he continue to be an outlier or will others start to catch him? Thanks.

I don’t see him being affected much, if at all, by those changes because teams don’t shift against him in a big way. Statcast shows 1 shifted defense against Diaz in 542 PA this year. They pull the shortstop toward the 6-hole a little more, but with the 2B being limited from crossing 2nd base in the new rules, there could be just marginal benefit to Diaz.