Much has been made of the tepid free agent market over the past two MLB offseasons. Owners who were once willing to hand out nine-figure contracts like candy suddenly became frugal, leaving many established veterans on measly one-year contracts or minor league deals. This belt-tightening led to the first year-to-year payroll decline the MLB has experienced in nearly a decade. All the while, total MLB revenues reached a record $10 billion in 2018.

In a recent player poll by The Athletic, the average player rated his frustration at the current labor and free agency situation a 4 out of 5, with 5 being extremely frustrated. That type of discontent has many speculating that significant labor strife might be on the horizon, potentially culminating in a lockout after the current collective bargaining agreement expires in 2021 or, even worse, a midseason strike.

One thing is for sure: The CBA is woefully outdated and needs to be overhauled. However, the vitriol building against MLB owners, highlighted by accusations of outright collusion, is unwarranted. Both the owners and the players union are complicit in crafting a system that stifled the earning potential of younger players and fattened the paychecks of underperforming veterans for decades.

The current CBA is predicated on a perverted model that underpays players during their prime years but significantly overpays them in free agency. Teams exclusively control player rights for their first six MLB seasons, significantly shortchanging them during that span. The MLBPA, a union historically controlled by older veteran players, were on board with this injustice so long as owners reciprocated by handing out big-money, long-term contracts in free agency.

With the advent of analytics, owners and general managers began making more intelligent decisions about how to spend money. This shift led to a decline in demand for free agents on the wrong side of 30. Given that WAR per plate appearance peaks from 26 to 28 and declines rapidly thereafter, exercising fiscal restraint with a largely 30 or older free agent cohort is probably a sensible decision.

Unfortunately, the service time and arbitration system that strangles the earning potential of younger players provides no built-in mechanism to redistribute the savings owners are now accruing. As a result, team payrolls declined in 2018 for the first time in nearly a decade, and they look set to decline 2019 as well.

Establishing Baselines

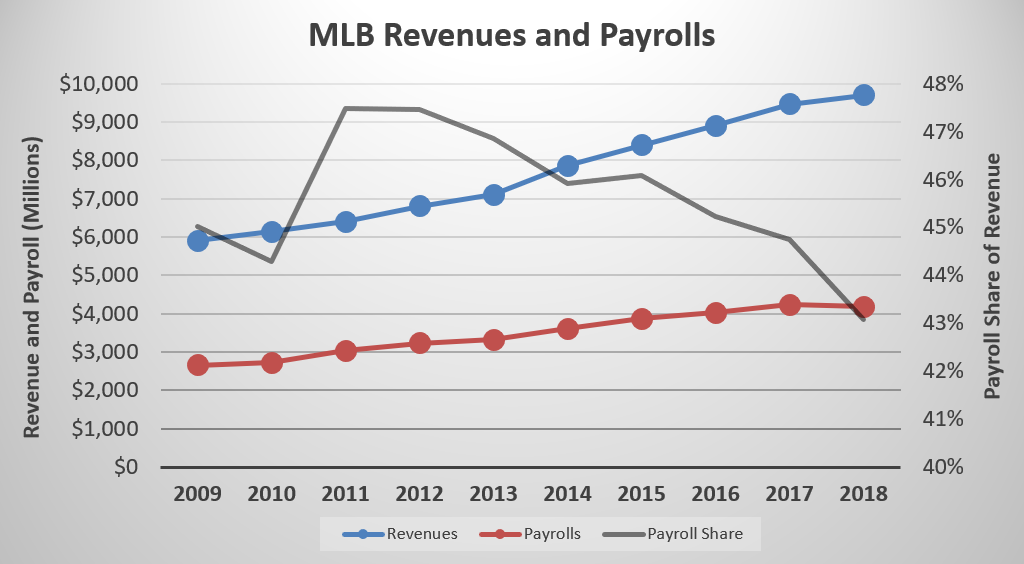

Despite all of the complaints lobbed MLB’s way about the pace of play, fan engagement, and attendance, the league is doing quite well for itself from a financial perspective, with revenues growing from $6 billion in 2009 to $10 billion in 2018, a compounded annual growth rate exceeding 6%. Considering that the sales growth performance of the S&P 500 over the same period clocks in at 4.2%, the commissioner combination of Bud Selig and Rob Manfred should be commended for growing their business better than most of America’s Fortune 500 Companies.

Revenue growth has slowed to about 4% annually since 2015 as the bumps from a glut of early-decade regional TV and national advertising deals subsided somewhat.

Growth in player salaries has largely followed suit over the past decade. In 2009, the league spent roughly $2.6 billion on player salaries, with that figure increasing to more than $4.2 billion in 2018, 5.2% annually. Payroll share as a percentage of overall revenue has stayed in a fairly consistent band of 44% to 47% in that span, although it did drop below 43% for the time first time in 2018.

Note that the above revenue figures, taken from Forbes, are considered “baseball-related revenue.” Baseball-related revenue includes all ticket and merchandise sales, TV contracts, and advertising deals. However, they notably exclude tangential revenue sources, such as team-owned television stations (e.g., Yankees and YES Network) or real estate developments (e.g, Atlanta Braves and The Battery Atlanta). Forbes estimates that the inclusion of non-baseball-related items would bring league revenues to $12 billion. Considering that leagues such as the NHL and NBA pay their players a fixed 50% of overall league revenue, there is clearly room for players to earn a larger share of the pie (although it is important to note that other leagues do not spend nearly as much on player development as MLB teams, many of whom invest in academies in foreign countries, so a low player salary share of revenue doesn’t necessarily mean owners in the MLB are earning more than other leagues).

Unfortunately, recent trends indicate that players are getting a smaller share, with payrolls declining from 2017 to 2018 for the first time in nearly 10 years. This trend is showing no signs of slowing, with opening day payrolls for 2019 tracking significantly below 2018 as well.

Spending Parity

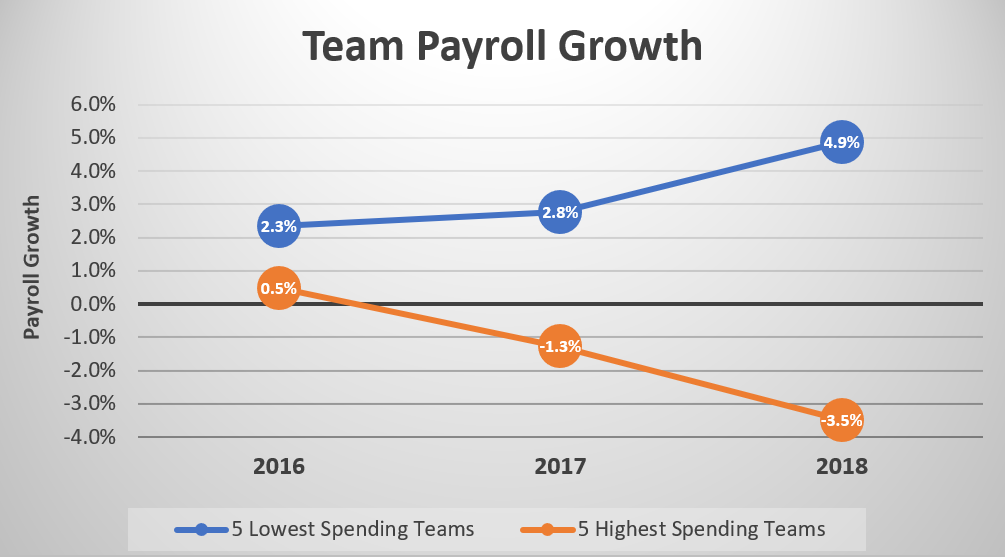

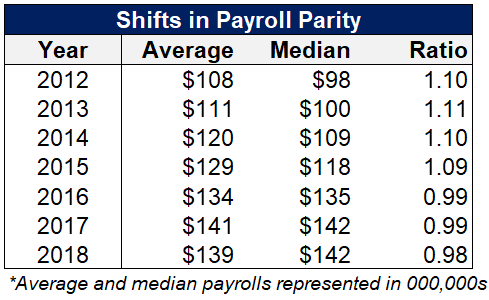

While overall spending on player salaries has declined in recent years, the composition of that spending among teams has shifted considerably. Quite often, small-market teams bear the brunt of criticism from fans and journalists for their lack of spending. However, that’s a story line that bears little truth in recent years.

The average payroll of the five lowest-spending teams in baseball grew by 2.3% in 2016, 2.8% in 2017, and 4.9% in 2018. Meanwhile, the average payroll of the top five highest-spending teams has actually experienced year-over-year declines recently, falling by 3.5% in 2018.

For years, many complained about the lack of payroll parity in baseball, with teams such as the Yankees and Red Sox dominating spending in the free agent landscape of the early and mid-2000s. Encouragingly, this environment doesn’t really exist anymore. In 2012, the league average payroll exceeded the median payroll by 11%, highlighting the inequality that existed among teams. However, in 2018, the average team payroll fell below the median payroll, the result of small- and large-market teams converging in their spending.

Recent payroll declines can be largely explained by two teams — the Los Angeles Dodgers and New York Yankees — reigning in their spending. In 2015, these teams had combined payrolls exceeding $500 million, but by 2018, they dropped to $375 million, a massive 25% decline over three years.

There are several potential reasons for this shift. The 2017 CBA introduced harsher luxury tax penalties with the introduction of an additional 12% surtax, along with draft pick penalties, for teams exceeding the luxury tax threshold by $20 million to $40 million. Yet the trends of big-market teams spending less started prior to 2017, and the additional penalties don’t present a large enough disincentive above the existing penalties to cause such a large change.

The bigger factor at play is how advances in analytics and aging curves have changed the value teams place on aging stars. These teams are simply not going to hand a $153 million contract to a 30-year-old Jacoby Ellsbury again or trade for more than $40 million in annual commitments to aging stars such as Carl Crawford and Adrian Gonzalez.

Exclusivity

The NHL permits players to earn unrestricted free agent status at the earlier of their 27th birthday or their seventh professional season. NFL players hit free agency after their fourth season, which comes at 26 or 27 years old for most players. Most NBA players earn unrestricted free agent eligibility from 26 to 28 years old. Each of these leagues also includes a restricted free agent system that allows players to sign contracts with other teams prior to earning unrestricted status.

Meanwhile, since 2014, the average MLB free agent signing was 33 years old. How is that possible?

MLB teams exclusively own a player’s rights for the first six seasons of their careers. Teams can stretch this control to seven if they manipulate a player’s service time by keeping him in the minors to start the season. The player then earns close to the MLB minimum of $555,000 for the first three seasons of his career. From there, they enter the arbitration system for three or four years, which grants them higher earning potential but ultimately still well below their market value. In the offseason following his 2015 AL MVP season, his third straight with a WAR above 5.5, Josh Donaldson was set to ask for a mere $11.8 million at arbitration.

In the case of Donaldson, a late bloomer whose service time clock didn’t start meaningfully ticking until 2012 when he was already 26 years old, he didn’t earn free agency rights until this past offseason, at 33 years old. Donaldson’s career cash earnings through 2018 were $59 million, a hefty face value sum but ultimately a pittance when considering his career 36.5 WAR ($1.6 million/win). On the downswing of his career and plagued with injury issues in 2018, Donaldson’s first foray into free agency resulted in a one-year contract from the Atlanta Braves. He’ll likely never be able to recoup the excess value he provided to the league during his prime.

Donaldson’s situation is becoming increasingly common, with owners backing off their implicit promise to break open the checkbook in free agency regardless of whether player performance has already begun declining. Consider that in the 2010-11 offseason, the Boston Red Sox handed a soon-to-be 32-year old Adrian Beltre a five-year, $80 million deal following an injury-plagued season with a career-worst 81 wRC+. While Beltre proved to be the incredibly rare player who gets better with age, that’s a contract that wouldn’t exist today.

In addition to the six years of MLB control, teams are entitled to maintain control of minor league players for six years. That means that teams could own exclusive rights over a player for their first 12 professional seasons. Such is the case with Royals’ second baseman Whit Merrifield, who spent a full six years in the Royals system before his major league debut. He will be eligible for free agency at 34.

Young Man’s Game

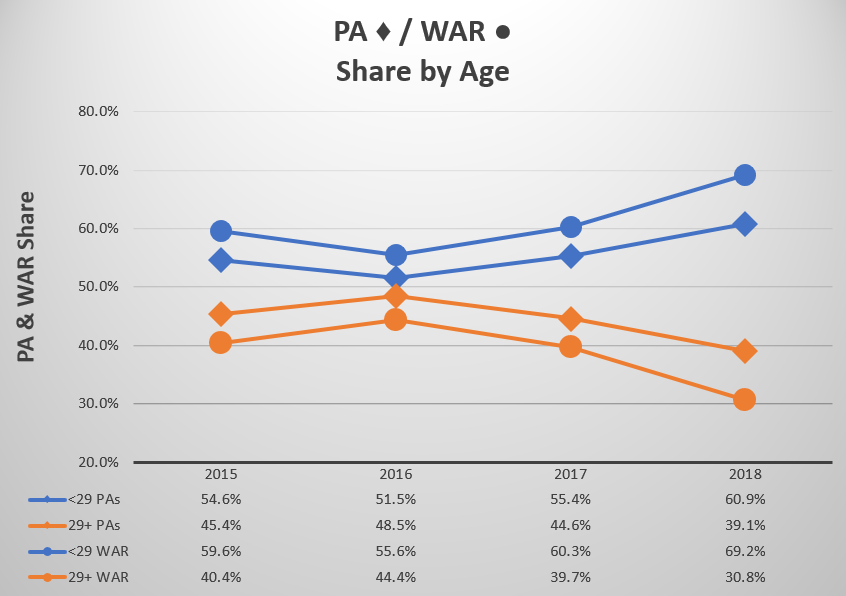

The shift away from signing older players to long-term contracts has led to an increase in demand for younger players. Concurrently, younger players are entering the majors more MLB ready than ever before. The combination of these factors is turning baseball into a young man’s game.

In 2016, hitters younger than 29 occupied a 51.5% share of all plate appearances and 55.6% of WAR. By 2018, those figures rose to 60.9% and 69.2% respectively. The increasing positive differential between WAR and plate appearances indicates that not only are younger players earning more opportunity, they are also getting better. Meanwhile, older players are earning less playing time and doing less with it. (Interestingly, this trend doesn’t exist for pitchers. Full exploration of this phenomenon will be left for another article.)

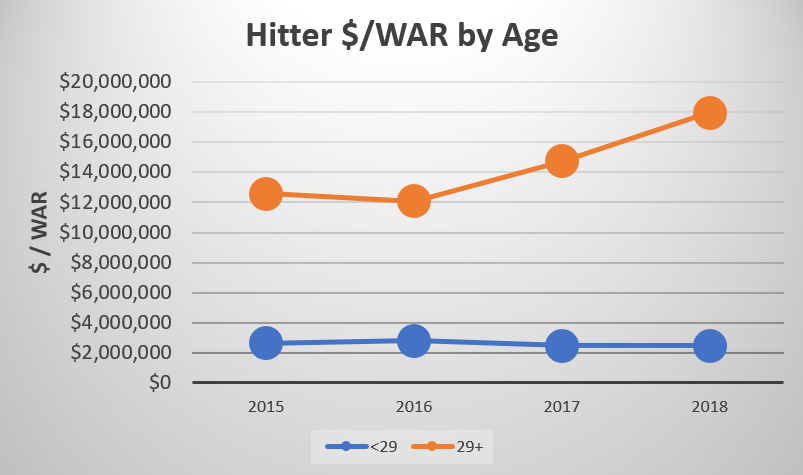

Despite this significant change, young players are still earning the same as they did before, at approximately $2.5 million per win. Meanwhile, older players are actually earning significantly more for their production, with their dollars per win increasing from $12 million in 2016 to $17.5 million in 2018.

In 2018, players 29 and older were paid 7.3 times that of younger players for equivalent production. No wonder owners are reticent to hand out contracts to 32-year-olds in free agency; they can likely replace them with a younger player and pay a fraction of the price for the same results.

While most industries feature pay disparities between young entrants and veterans, the MLB is operating on a ludicrous inequality scale. The unfortunate reality is that the MLBPA allowed this inequality to persist because it disproportionately benefited the most powerful voices in the union: older players.

Solutions

Tony Clark and the MLBPA leadership failed their union in the last round of CBA discussions. Fresh off multiple years of 5% or more annual payroll growth, the union heads were content to preserve the status quo, completely failing to anticipate the changes occurring in regard to analytics and opportunities given to young players.

Why was the MLBPA slow or unable to anticipate these changes? Probably because it was comfortable with a system that richly rewarded veterans at the expense of young players. Pushing for the sweeping change needed to oust MLB’s outdated service time system would require union representatives such as Curtis Granderson to prioritize the salaries of 25-year-olds ahead of their own.

A more equitable distribution of pay among younger and older players should be the top talking point at the next round of CBA discussions in 2021. Such a system will not only spread salaries more fairly across the age spectrum but would also reduce the surplus value owners extract from player production.

To achieve this goal, I would suggest the following changes:

Service time calculations should include minor league seasons: Teams currently control a player’s rights for six full MLB seasons before he can sign with another team. I propose calculating service time based on professional seasons, inclusive of minor league years, while bumping the threshold from six to seven. In this scenario, a player debuting in the minors at 20 years old would become a free agent at 27 or 28, depending on his birth date. Not only would this system enable players to capitalize on their earning potential during their prime years, but it would also eliminate the service time manipulation that arises when teams keep players in the minors for extended periods to maintain their control, such as the White Sox did last season with Eloy Jimenez.

Raise the minimum salary: The current MLB minimum salary of $555,000 is 15% lower than the $650,000 minimum in the NHL, a league whose aggregate revenue is less than half of MLB’s. The minimum MLB salary should be increased to $1 million, which will go a long way in increasing the long-term quality of life for the many players who are not fortunate enough to carve out long-term careers.

Restricted free agency replaces arbitration: The arbitration process is an arbitrary one that wastes resources. Consider that both MLB and the MLBPA must spend money to hire mediators and lawyers while also investing time to build cases. A restricted free agency system could replace arbitration, save the league and union money, and provide more efficient results. This system exists in the three other major North American sports and would allow teams to still control a player’s rights, just not exclusively. For instance, once a player finishes his third season, other teams would be able allowed to offer him a contract (often called an “offer sheet”). The original team would have the exclusive right to match the offer; however, if the team doesn’t, the player is free to sign with the offering team. There is often some type of compensation — usually involving draft picks — that would flow from the offering team to the original team in exchange for signing the player.

Increases in minor league pay:Minor league players are not represented by the MLBPA, nor do they have a union themselves. As a result, some make as little as $1,100 per month, with players often having to bunk up three or four to a bedroom in order to make ends meet. While the MLBPA has no technical obligation to improve the pay of minor league players, it should bargain on their behalf in the next CBA if it is serious about redistributing funds from the owners’ pockets in a fair manner.

The above changes would distribute the massive revenue that MLB draws in a much more fair, efficient manner among players across the professional spectrum. It would also likely prevent the owners from lining their pockets because they would need to compete among each other to retain the services of talented younger players. Some suggest the MLBPA should insist on a fixed revenue split flowing to the players, which would likely necessitate a hard salary cap. However, owners already seem to be preparing for such a scenario by establishing sources of non-baseball revenue that they would look to exclude from the revenue calculations.

The best bet for players and the health of baseball as a whole is to embrace a more competitive, market-based structure for the payment of players of all ages.

(Graphic by Justin Paradis. @freshmeatcomm on Twitter)

The Red Sox signed Beltre to a one-year deal for the 2010 season. It was the Texas Rangers that opened the checkbook for him in 2011 onward.

I am on board with all of the proposed changes you outlined, and like them a lot. It’s a great article! But I struggle to justify why the owners would accept those changes? This seems like 4 sweeping changes that benefit players more than the existing system. The players don’t really make any concessions in there that I see. I’m assuming most of us fans side with the players, not the owners, but I imagine they’d need something in their favor.