As heralded Boston hero David Ortiz stood on the mound at Fenway Park, eyes welled up and standing tall, connecting with every fan as he tapped his heart, the Red Sox faithful had then realized that the dream was now over. Ortiz’s final season was never supposed to end at the hands of a short-handed Cleveland Indians squad—forget that it was a sweep in that 2016 American League Division Series. For the three-time champion, this was not the goodbye planned.

While fans reminisced of the past glory, that moment also signaled a change of the guard. Mookie Betts broke out, finishing runner up in the AL MVP voting. David Price was just signed to a long term contract the offseason before and pitched to a 3.58 ERA in the second half. Hanley Ramirez hit 30 home runs and drove in 111 runs. Red Sox General Manager Dave Dombrowski would trade for Chris Sale to strengthen the pitching staff, a big addition to hopefully offset the offensive downgrade from not having Ortiz in the lineup. Then there was the reigning AL Cy Young winner, Rick Porcello. He was a much-maligned winner that season among the baseball community, given that Justin Verlander rode a 1.96 ERA in the second half to push himself to impressive season totals.

Whatever your thoughts on who the winner should have been were, that Cy Young accolade came from an evolution that few pitchers can make, on the backs of the analytical revolution baseball was going through with spin rates and movement metrics. Porcello went from a sinkerballer in Detroit to a fly-ball and decent strikeout pitcher with the Red Sox. Throwing many four-seamers and curveballs, complemented with the sinker and occasional slider, Porcello was a complete pitcher who could throw a pitch to any part of the zone. After trading Yoenis Cespedes then immediately giving the right-hander a five-year extension before the 2015 season, former Red Sox General Manager Ben Cherington looked like a genius.

Though in the next three seasons, Porcello struggled and never resembled the steady ace of 2016, resulting in a 4.79 ERA with a 4.45 FIP and 4.46 xFIP. The question is, where did it all go wrong?

Trouble With Two Strikes

One of Porcello’s greatest strengths is getting ahead in the count and throwing as many pitches as he can in those situations. In 2016, Porcello had the third-highest number of pitches thrown ahead in the count at 33.5% (of pitchers with at least 2000 pitches thrown), while he had 31.5% of his pitches with two strikes—16th highest.

More impressively, the right-hander was able to put opposing hitters away with two strikes.

| Pitch% | SwStr% | League Average SwStr% | xwOBA | League Average xwOBA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-Seamer | 32.2 | 16.8 | 11.8 | 0.194 | 0.259 |

| Sinker | 32 | 4.4 | 8.7 | 0.27 | 0.273 |

| Curveball | 11.7 | 7.1 | 17.6 | 0.196 | 0.186 |

| Changeup | 11.2 | 19.2 | 18.2 | 0.161 | 0.217 |

| Slider | 12.5 | 15.7 | 19.2 | 0.182 | 0.198 |

Porcello leaned on his four-seamer and sinker heavily, with a roughly even split among the rest. The swinging strike rate on his four-seamer stands out as it was 42% better than the average—don’t forget the changeup as that also registered an above-average rate. Take notice of the curveball too, as while the pitch did not generate a large number of swings and misses, the breaker still ended up with roughly league-average xwOBA.

The former Red Sox ace was again on the leaderboards this past season with the percentage of pitches thrown ahead in the count (fourth) and with two strikes (19th).

Unfortunately, Porcello was not able to put them away over the next three seasons.

| Pitch% | SwStr% | League Average SwStr% | xwOBA | League Average xwOBA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-Seamer | 36.7 (39.4) | 13.6 (10.9) | 12.6 (13.2) | 0.253 (0.269) | 0.264 (0.256) |

| Sinker | 19.8 (15.5) | 3.4 (2.8) | 8.2 (8.3) | 0.264 (0.283) | 0.285 (0.272) |

| Curveball | 10.0 (10.1) | 15.0 (11.5) | 17.2 (17.1) | 0.259 (0.273) | 0.204 (0.202) |

| Changeup | 9.7 (9.8) | 10.3 (7.5) | 17.1 (17.0) | 0.269 (0.293) | 0.231 (0.225) |

| Slider | 23.2 (25.1) | 13.8 (11.2) | 19.4 (19.3) | 0.253 (0.257) | 0.203 (0.203) |

There was a steep drop off for Porcello, with this four-seamer cratering in productivity—especially in 2019. Despite the sinker and four-seamer producing a better than league average xwOBA statistic, even that disappeared in 2019.

Since there was no pitch Porcello could use with two strikes last season, there could be a question with how he’s using his pitches once he gets to a favorable count.

Given how successful high four-seamers have performed, let’s take a look at how often he’s placing his four-seamer at the top of the zone with two strikes.

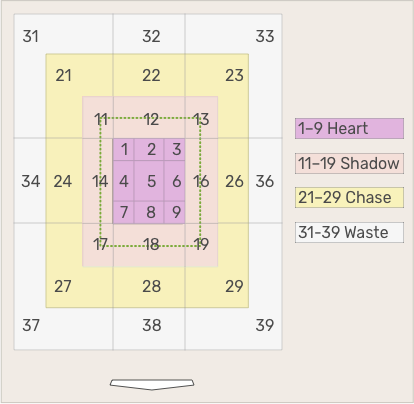

For those that need a refresher, the Statcast ‘Attack Zones’ are shown below.

In the table below, you’ll see ‘Zone 1’—its composition being 11, 12, 13, 21, 22, and 23—the combination of shadow and chase areas as the top of the strike zone.

| Pitch% | Whiff% | |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 26.7 | 27.8 |

| 2017-18 | 24.3 | 20.7 |

| 2019 | 27.2 | 16.8 |

Porcello threw his four-seamer at an even higher rate than he did in 2016, though he generated far fewer whiffs. Given that the heater was used correctly, with the high spin nature of the pitch, that higher usage seems justified. However, the number of whiffs of those particular pitches dwindled, therefore negating the supposed positive effect of throwing his fastball up.

Furthermore, we observed that the slider was used prominently with two strikes this past season earlier. This is where we’ll take a look at how often Porcello put the slider low in the zone.

Likewise, for this table, you’ll see ‘Zone 2’. This encompasses the 17, 18, 19, 27, 28, and 29 areas—the shadow and chase locations at the bottom of the zone, again with two strikes.

| Pitch% | Whiff% | |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 25.4 | 40.9 |

| 2017-18 | 28.4 | 42.9 |

| 2019 | 18.0 | 35.3 |

For reference, Ken Giles‘ slider this past year had a 59% whiff rate with our criteria so clearly Porcello’s spinner is not even closer to being an elite swing and miss pitch. Nevertheless, his slider has not only induced fewer swings and misses over the years, but the right-hander was not very accurate with it in two-strikes counts as shown by the 18% mark.

Overall, you can still see signs that Porcello has been using his key pitches with two strikes logically, so there must be an issue with the movement of his pitches.

Looking At His Arsenal

For a pitcher, his point of attack is determined by what tools he has. Of course, Porcello is no different and if there’s a change in how his pitches move, then there needs to be a change in how he pitches.

You’ll notice through this that there is no mention of the sinker. That’s because the pitch is not vital to his success. He has it, but as a contact pitch, lacks application in Porcello’s dwindling production. We want to focus on pitches that could help him generate more swings and misses.

Changing It Up

The simplest pitching arsenal is the fastball and changeup.

For many years, Porcello’s changeup was not a focal point against opposing hitters. From 2009 to 2017, the wOBA on the changeup was .311, speaking to the ineffectiveness. However, Porcello had a rocky 2017 in which his four-seamer, curveball, and slider were not enough to get him across the line, struggling to a 4.65 ERA. The changeup was the pitch that not only moved to his arm side but also gave him another pitch that was roughly 10 miles per hour slower or greater with his curveball.

In 2018, Porcello was told by former Red Sox pitching coach Dana LeVangie that he should lower his arm slot to add more movement to his changeup. The key to a wipeout changeup is having significant arm-side action with a good amount of ‘drop’.

To illustrate my point, here is a changeup from Luis Castillo.

Luis Castillo, Changeup Release/Spin Axis (Slow) pic.twitter.com/g6Gl97Dked

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) August 1, 2020

LeVangie’s advice came in handy and the changeup ended up being a weapon.

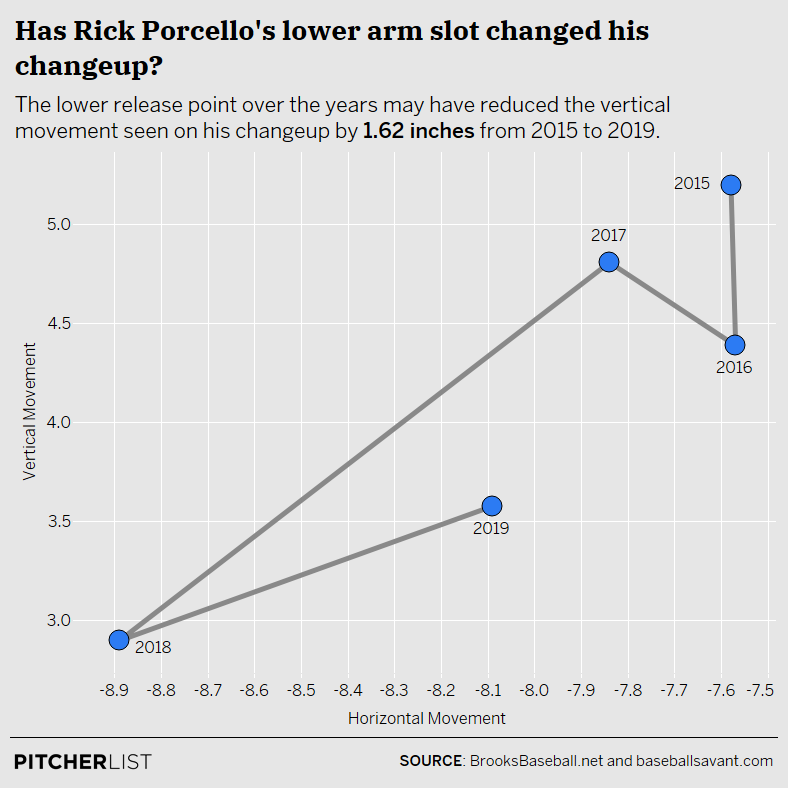

You can see that 2018’s version of the changeup had the greatest amount of horizontal movement—for those wondering, the negative value implies movement to the right side from the pitcher’s point of view, which in Porcello’s case is arm side. It also had the least amount of vertical movement since 2015, just under three inches. With less vertical movement, there is less spin counteracting gravity creating the desired ‘drop’. With the best of both dimensions, Porcello’s changeup ended up with a .295 xwOBA—the lowest mark of his career in the Statcast era.

https://gfycat.com/disloyalthirstyammonite

The results would, unfortunately, be short-lived. Porcello’s changeup in 2019 was brutally dealt with to the tune of a .365 xwOBA. The graph also details the loss in horizontal movement and gain in vertical movement, both detriments to a wipeout changeup.

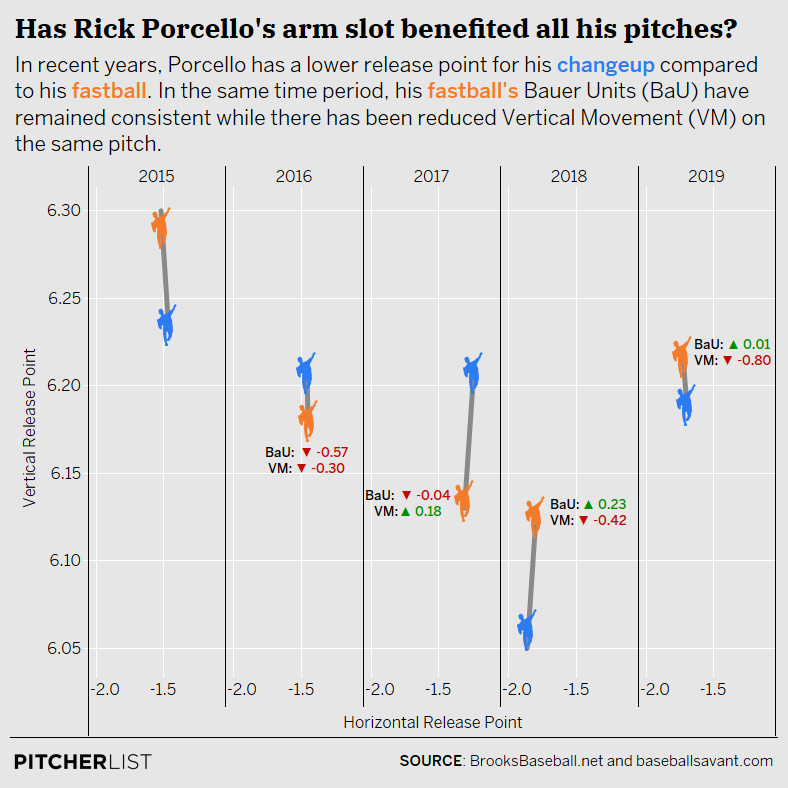

The problem is that once the release point was altered, the complications to the four-seamer were detrimental.

Before we continue, there needs to be clarification on what is shown above. Now, the point made here is not necessarily that a higher release point is what makes a four-seamer have greater vertical movement—that’s not the case. Gerrit Cole has a fairly low arm slot, -2.13 ft horizontal and 5.84 ft vertical, even lower than Porcello’s, while also boasting the best four-seamer on the planet.

The key is keeping a strong wrist through the baseball, while your fingers are pointed directly skyward—at least up enough where the spin axis is close to vertical, decreasing the amount of inactive spin. In Cole’s case, that required having the sensation of ‘cutting’ the ball at the end. Given his past as a predominantly two-seam fastball pitcher where his natural wrist position going along his arm created by the release point, staying behind the ball was never the focus.

We’ll come back to this later on.

Side Spin

Simply put, Porcello’s slider is just bland.

https://gfycat.com/glisteningangelicanura

https://gfycat.com/agreeableinfantiledormouse

It has a ‘cement mixer’ sort of trajectory which supports its inability to generate whiffs.

While the slider had a .325 xwOBA last year, it also generated a frail 85.1 MPH average exit velocity. For reference, Adam Ottavino posted an 84.9 MPH mark last season with Noah Syndergaard close by at 85.4 MPH. With those numbers, it would seem that Porcello’s slider would be far more useful as a contact pitch, as a cutter, rather than being used for swings and misses.

Even though Porcello may have stumbled upon a good contact pitch amidst his new transformation, he’s also ruined the pitch that set up his four-seamer the best: the curveball.

I’ll show you two different curveballs from last season: one from Adam Wainwright and another from Porcello. By choosing these two, we are looking at curveballs with very similar speeds (~75 MPH) from three-quarter arm slots. Furthermore, I chose similar locations so we could best compare the movement.

https://gfycat.com/idioticcostlybaboon

https://gfycat.com/niftylateantelope

In the arc of Wainwright’s breaker, spot the sharpness of the break between half and three-quarters of the way to the plate. The spin on the baseball is dictating the movement of the ball, moving left and down simultaneously.

With Porcello’s, you see it float up to the plate, though with a good amount of sideways spin. But at 75 MPH, that spin is just not enough to make it a viable option. Since the ball does not drop as much as it should, the pitch ends up getting hammered when even left slightly up, evidenced by a .355 xwOBA last season.

There was a time where Porcello’s curveball exhibited exceptional downward movement—do you know when that was? 2016. That movement was also on display in 2015 and 2017 but fell wayside in 2018 and 2019.

| Horizontal Movement | Vertical Movement | |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 7.76 | -8.56 |

| 2016 | 8.27 | -8.13 |

| 2017 | 7.94 | -6.56 |

| 2018 | 9.07 | -6.22 |

| 2019 | 8.35 | -5 |

Now, I know what you’re thinking. We talked about how Porcello lowering his arm slot had an impact on his four-seamer. Could lowering his arm slot have done the same to his curve? The answer is no.

Wainwright talked about his curveball with Fangraphs last year. The point he makes is that as he’s gotten older, his arm slot has dropped and subsequently added more horizontal movement than in the past since the pitch takes the shape of the arm—think about that 12-6 hammer to strike out Carlos Beltran in the 2006 National League Championship Series. Though through that entire time, Wainwright has still been able to maintain excellent downward movement on his curveball despite the ever-lowering arm slot. So what gives?

If you have time, check this video segment from MLB Network about Wainwright’s curveball. The St. Louis right-hander did not spend much time on this particular point but the fingers rolling on top of the ball is key—that’s how you get the topspin. Topspin is critical to creating downward movement and it’s entirely dependent on the correct wrist position, which is talked about in the video. Additionally, the topspin mirrors the backspin of the four-seamer, making the two pitches indistinguishable to the hitter.

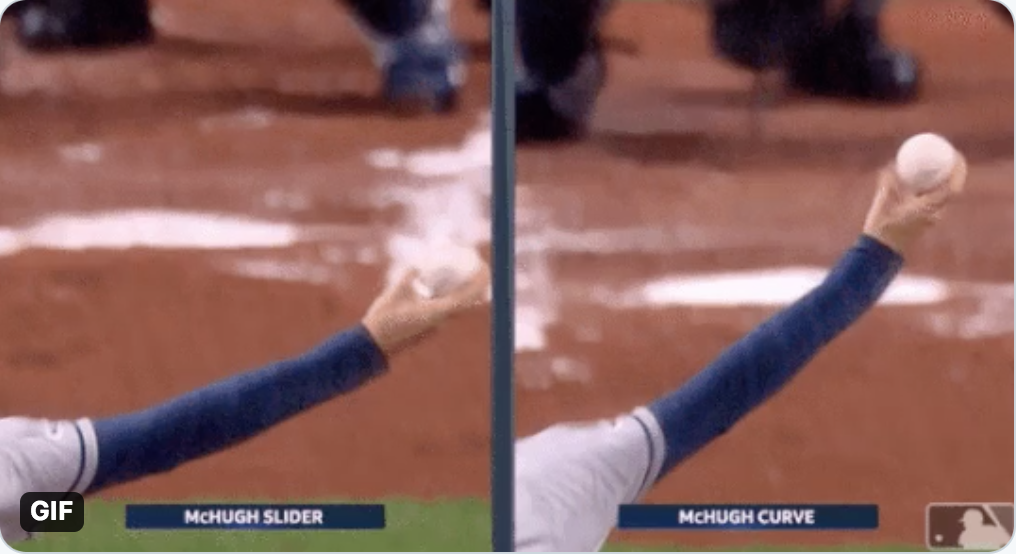

After spending all this time on the slider and curveball, the two hardly seem to connect at this juncture. But just take a look at this GIF and subsequent image, where former Houston Astro Collin McHugh’s slider and curveball releases are under the microscope.

Collin McHugh, Slider and Curveball (comparison)

[From the Astros broadcast] pic.twitter.com/YXmRPSzEy6

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) March 31, 2019

With his slider, McHugh’s dominant fingers—index and middle—are both visible and off the side of the ball. Ergo, the spin created is more side to side than up and down. The curveball is completely different, as the middle finger is not visible, as both are seemingly running over the top of the ball.

Let’s also compare wrist positions. On the slider, the wrist follows the arm with very little input on the trajectory of the pitch. Meanwhile, McHugh’s curveball comes from a strong wrist, creating a near 45-degree angle with his forearm, making sure that his fingers are on top of the baseball despite the low arm slot.

These are the differences that have made Porcello’s slider so detrimental to his curve. As we saw with the movement of Porcello’s curveball since 2015, the downward movement lessened between 2016 and 2017, which is where the right-hander first increased his slider usage from 12.8% to 16.9%, eventually reaching 24.4% in 2018. It’s important that Porcello creates a clear distinction mentally between what spins he wants to get from each pitch instead of muddling the spins.

Last Thoughts

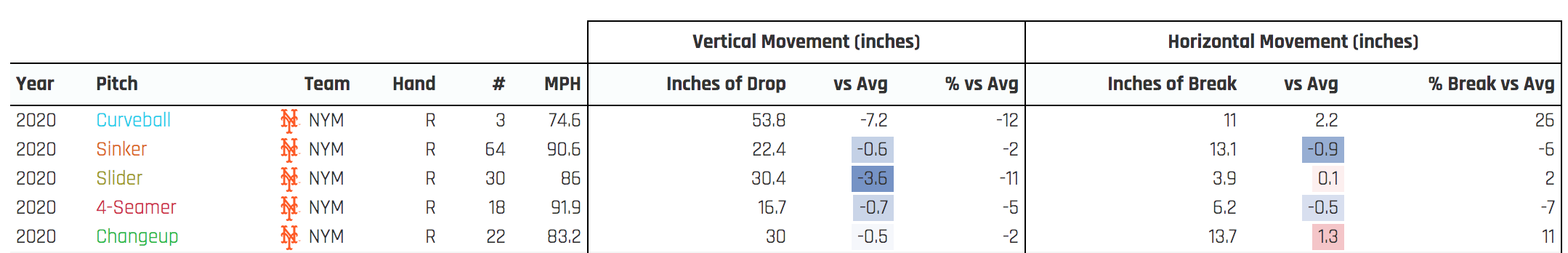

Porcello has now thrown two starts in a New York Mets uniform and both have been disastrous, to say the least. In 2020, Porcello has become a pitcher the Mets are used to having on their staff—four-seamer, sinker, slider, and changeup. Syndergaard, Jacob deGrom, Steven Matz, and Marcus Stroman all display those pitches (except deGrom does not throw the sinker). This has resulted in Porcello throwing only three curveballs in his two outings, a shocking development given the heavy reliance on the pitch while in Boston.

Even though the poor results have dominated the talk, there have been noticeable changes worth discussing.

First, Porcello has been able to add some velocity to his fastball, increasing from 91 to 92 MPH on his four-seamer and 90 to 91 MPH on his sinker. This largely comes from a simple change in his mechanics in which he loads on his back leg for slightly longer before moving down the slope.

https://gfycat.com/welldocumentedchiefaustralianfreshwatercrocodile

https://gfycat.com/hardhollowflyingsquirrel

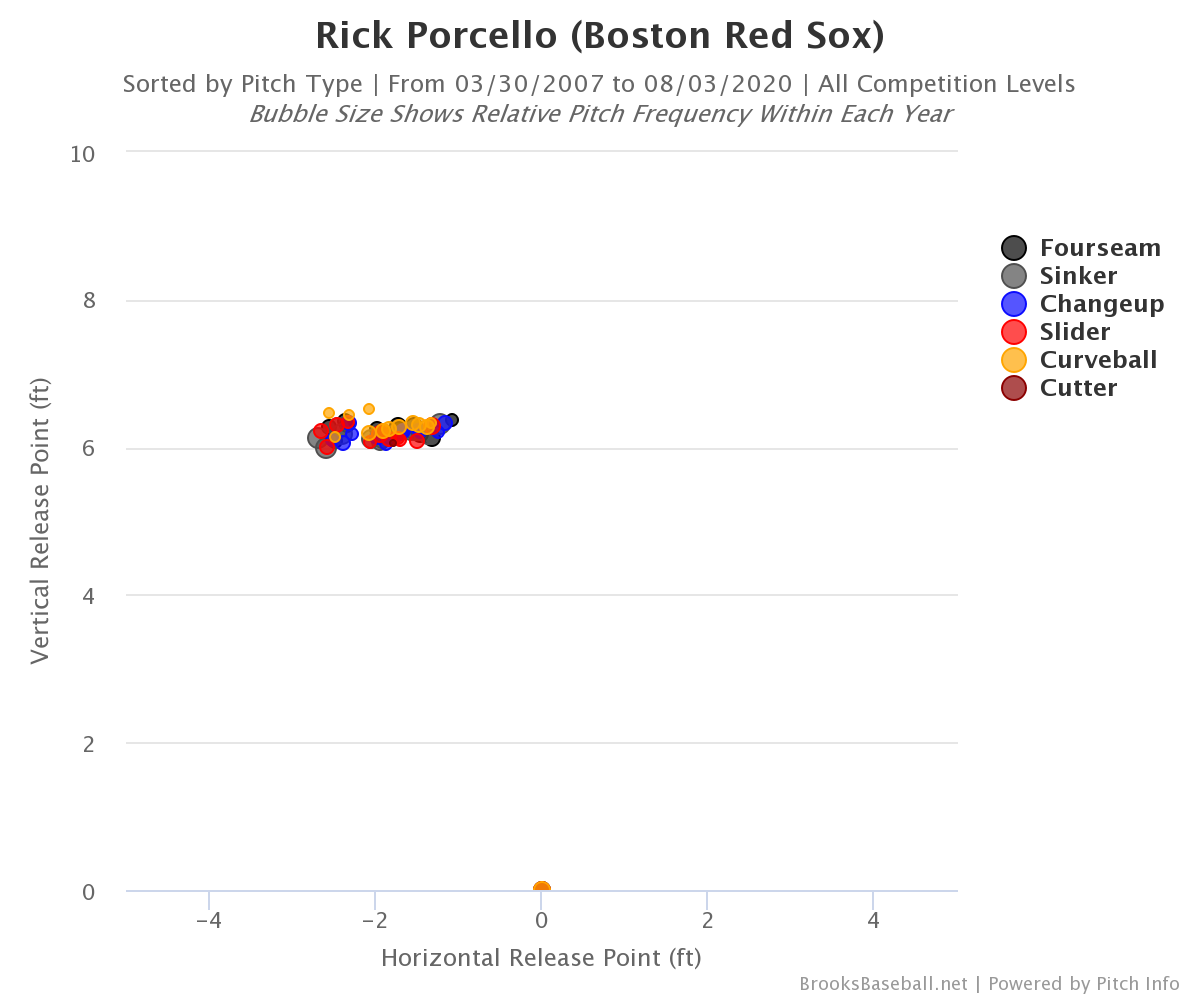

Second, Porcello has been able to regain a much higher arm slot.

*The black dot the furthest to the right in the cluster Porcello’s four-seamer release point from this season. The rest of his pitches are close by.

With that said, the movement profile as shown by Baseball Savant is highly disappointing.

As we discussed earlier, the release point is not everything.

With his curveball still not generating topspin and now sent to the proverbial doghouse, Porcello’s four-seamer now has nothing to tunnel with it at the top of the zone. If his curveball and four-seamer were right, the 29.5% of four-seamers he threw at the top of the zone last season, a league-high among pitchers who threw at least 250 heaters at the top of the zone, would be far more effective.

As the Mets continue to push sinkers and sliders on Porcello, the likelihood of improving on what he did last year is minimal—of course, there is nowhere to go up from his first two starts. Considering there was a time where Porcello had great four-seamer vertical movement and outstanding downward action to his curveball, it is a shame that the right-hander has not been able to put his elite spin to good use and is stuck to only pitching to contact.

Being one of my favorite pitchers, Porcello’s fall has truly been a painful one.

Photo by Rich von Biberstein/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Justin Paradis (@freshmeatcomm on Twitter)