The 2020 New York Mets were one of the best offensive teams in baseball. Their 122 wRC+ was tied atop MLB with the eventual World Series Champion Dodgers and their .347 wOBA was third behind the Braves and Dodgers. The best hitter on that team was not the all-time rookie HR leader Pete Alonso. It was not Michael Conforto. And it wasn’t Jeff McNeil, who matched Alonso in both wOBA and wRC+ in 2019.

It was Dominic Smith, whose 165 wRC+ was 6th in baseball, and who had seemingly become a forgotten man in Flushing Meadows. When he was called up in 2017, Smith came with some solid prospect pedigree—Baseball America’s #71 prospect, #55 for MLB Pipeline, and Keith Law had him at #29.

However, after dominating AAA pitching, Smith saw his K% increase and his BABIP plummet upon the call-up, resulting in a weak 74 wRC+ in 183 PA. By 2018, Smith had missed a shot to claim an everyday job, playing in 145 games over the 2018 and 2019 seasons.

But before Smith could be deemed a bust, a funny thing happened—he started hitting. Even in that part-time role in 2019, Smith posted a 133 wRC+, a huge jump from the 83 he posted in 2018. That turned out to be just a taste of what he would do in 2020.

A Whole New Look

If you saw Smith swinging the bat in Spring Training 2019 and found yourself wondering who the new guy was, you probably weren’t alone. Take a quick look at these clips of Smith – the first one from late in his 2017 debut…

…and then one from early in his 2019 breakout campaign.

Both of these swings turned into HR on pitches down and in, but there are more differences than similarities. A few things jump out. First, look at where he is when the pitcher comes set:

In 2017 (dark bat, facing Jake Barrett in the red jersey), the bat is on his shoulder, basically parallel to the ground; in 2019 (lighter bat, facing Shaun Anderson in the gray jersey), it’s off his shoulder, basically ready to hit. In 2017, he’s sitting a bit deeper in his stance, whereas he’s a bit more upright in 2019. He also appears to be a bit more open in 2017; in 2019, there’s less daylight between his legs. This might be due to camera angles, but both of these shots are of RHP vs. LHH matchups at Citi Field, so they should be fairly similar.

Now look where he is by the time the pitcher is releasing the pitch:

The differences are less drastic here, but he does still appear to be more open in 2017. In addition, because of where the bat and front foot started, he had to move a lot further to get into this position in 2017.

In February 2019, Smith did a Q&A with Baseball America and talked about these changes. Asked about the “root cause” of his issues, he said, “A lot of it was just like mechanically in my swing. You look at a lot of footage and tape over the last two years, I was doing so many things bad at the plate. This offseason I really worked hard on making it easier to have success. So I simplified a lot of my swing.”

There’s a lot more detail in that Q&A, including specifics on the swing change and some info on significant weight loss that may have contributed to his improvement, as well.

This is pretty great because we have a nice cohesive story here—Smith struggled, Smith says he is making a change, we see the change in on tape, and the results speak for themselves. The next logical question is how did those changes lead to those results.

Better Approach

The first place I always look for improvement is in plate discipline and, sure enough, Smith walked more and struck out less after the changes.

| Stat | 2017-18 | 2019-20 |

| K% | 28.9% | 22.5% |

| BB% | 5.4% | 8.3% |

| K/BB | .19 | .37 |

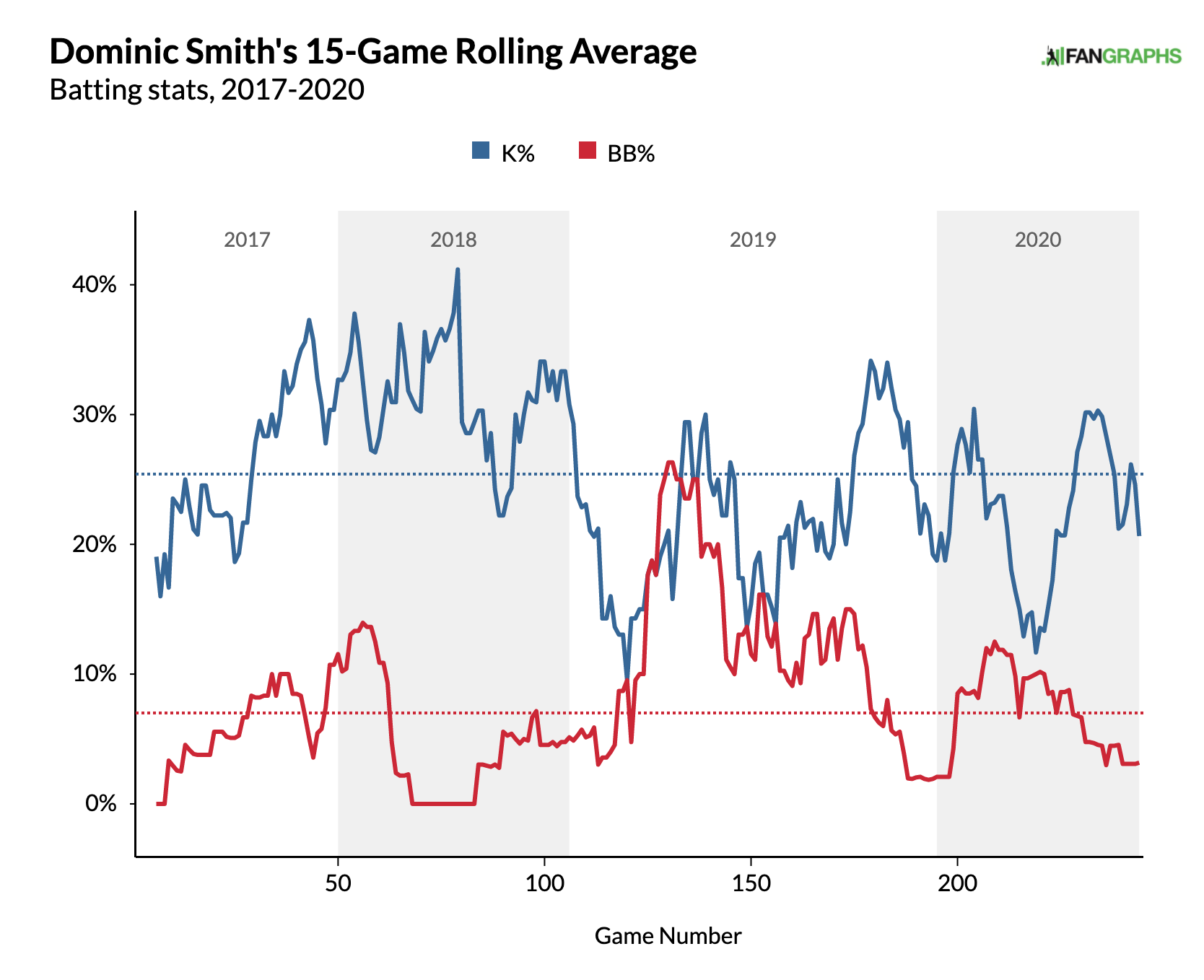

That’s pretty glaring. Smith nearly doubled his K/BB ratio by cutting his strikeouts and boosting his walks. He went from having problematic plate discipline to solid plate discipline. A look at rolling 15-game averages tells us a bit more.

Smith has shown improvement in his K-rate, while his walks peaked in early 2019 before settling back in closer to his career average. That said, his lowest walk rates and highest strikeout rates were before the change in stance and swing; his lowest strikeout rates and highest walk rates were after.

Going back to the Baseball America article, Smith noted about the change, “I’m a little bit taller now because when I was in my legs I would rock back too far and it would get me out on my front foot, and once I’m out on my front foot I’m trying to catch everything out in front and that’s what causing me to chase a lot of pitches.”

So did he chase less? Yes, though that isn’t the only shift in his plate profile.

| Stat | 2017-18 | 2019-20 |

| O-Swing | 37.4% | 35.8% |

| Z-Swing | 67.5% | 71.6% |

| Swing% | 50.5% | 50.2% |

| O-Contact | 60.6% | 65.0% |

| Z-Contact | 81.6% | 83.6% |

| Contact | 72.7% | 75.7% |

So, yes he cut back on his chase rate, but his overall swing rate barely moved. He chased less but got more aggressive in the zone, and then made more contact both in and outside the zone. He was more selective but, perhaps more importantly, he made more contact.

More Selective

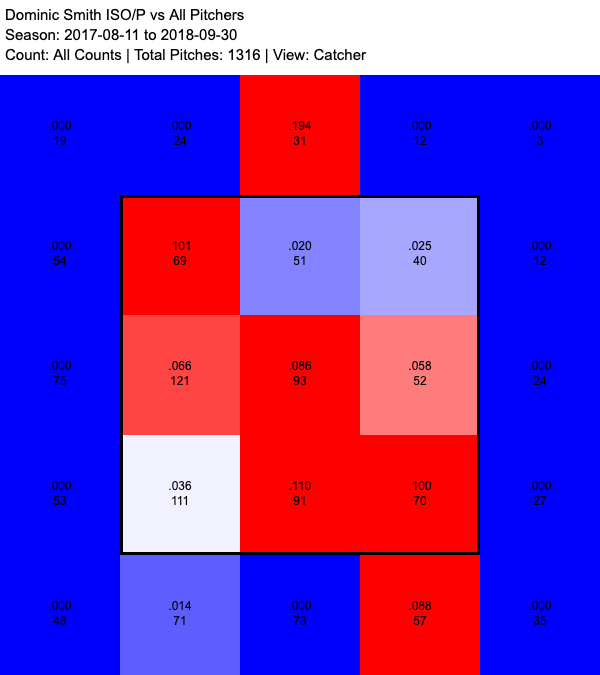

You can see his selectivity clearly in his two-year heat maps. Comparing swing charts, you see more concentrated red in the zone and a lot more blue outside.

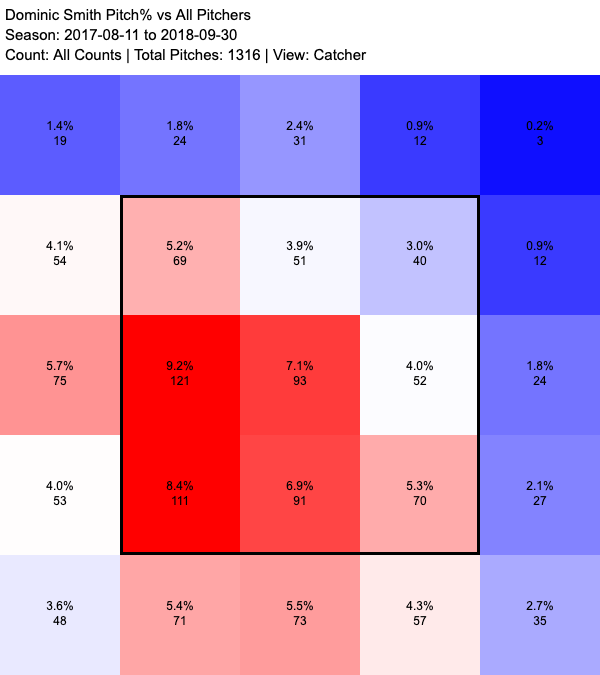

He is being more aggressive on pitches on the outside part of the plate, and it’s not hard to see why. In 2017-18, that is where pitcher’s attacked him:

Look particularly at those 9.2% and 8.4% zones – the places pitchers were most likely to attack him. If you go back to the previous GIF, they were his two lowest swing percentages in the zone in 2017-18. That leads to a lot of called strikes.

As for where he cut back, it was mostly up and out of the zone (or up and off the plate). And this also makes sense – those zones he made a high rate of contact compared to other places outside the strike zone…

…but the contact he made was awful.

If you swing at a lot of pitches up, and make contact with them a decent amount, and post an ISO of zero (0) on those pitches, cutting back the swings makes sense. And the one zone high with an ISO/P > 0 is the one he still “chases” most often.

More Contact

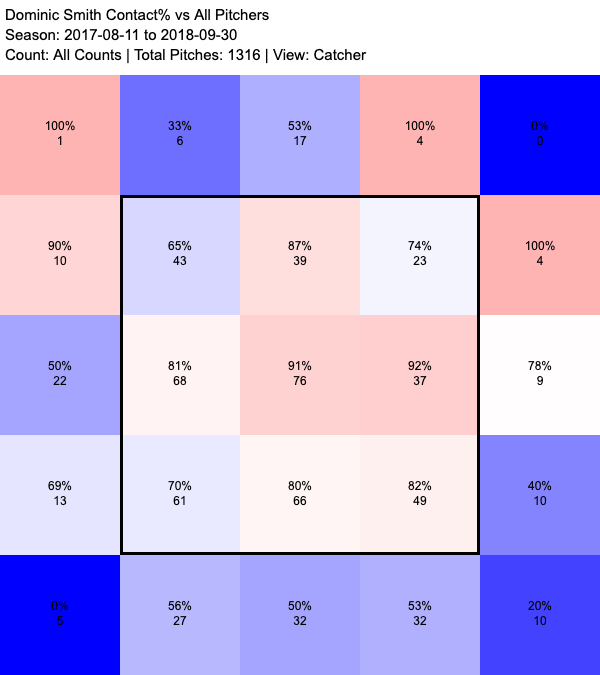

The first thing you can do on a pitch is decide to swing or not, and Smith got better at that—he swung more often at pitches he could hit and less often at pitches he couldn’t. The next thing you can do is make contact, and Smith did that better, too. If you go back to the table you’ll see that while his overall swing percent remained steady, his contact percent increased both in the zone and out of the zone.

Part of this is being more selective. If you swing at fewer pitches you can’t hit, you will swing through fewer pitches and make more contact, and he made more contact all over the plate. Out of the 25 zones in the GIF below, his contact rate increased in 15 zones and stayed steady in three more.

Of the seven zones where his contact rate got worse, two dropped by 3% or less. In the other five zones, he dropped his swing rate by an average of 8 percentage points. Again, evidence that he saw the ball better, made more contact, and where he couldn’t make more contact, he stopped swinging as much.

Better Contact

The biggest change isn’t that he was more selective or that he made more contact, however; it’s that he made better contact. You can see this no matter how you look at it.

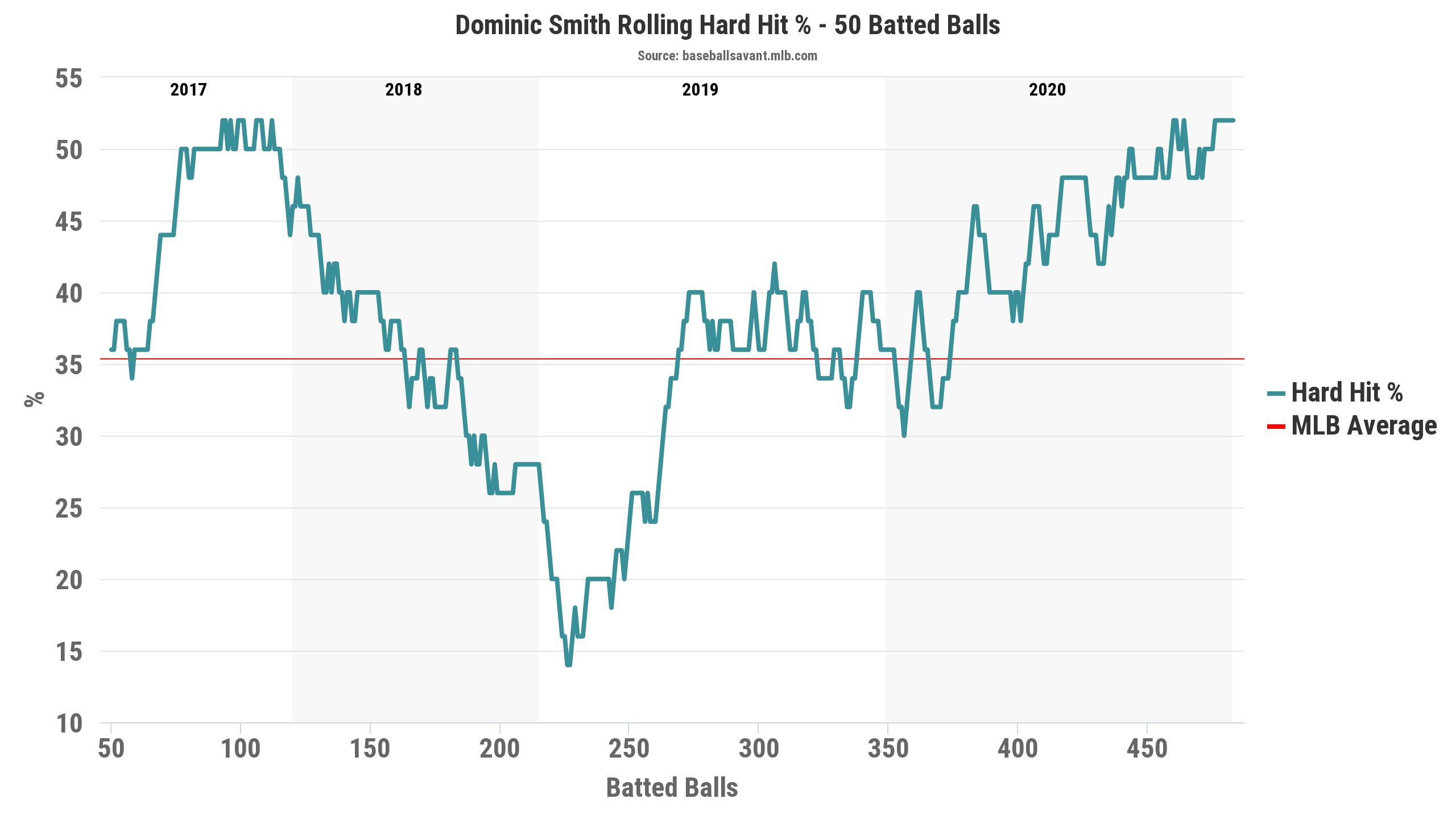

Want to look at how often he hits the ball hard? His Statcast hard-hit rate tumbled throughout 2018, but has climbed non-stop ever since.

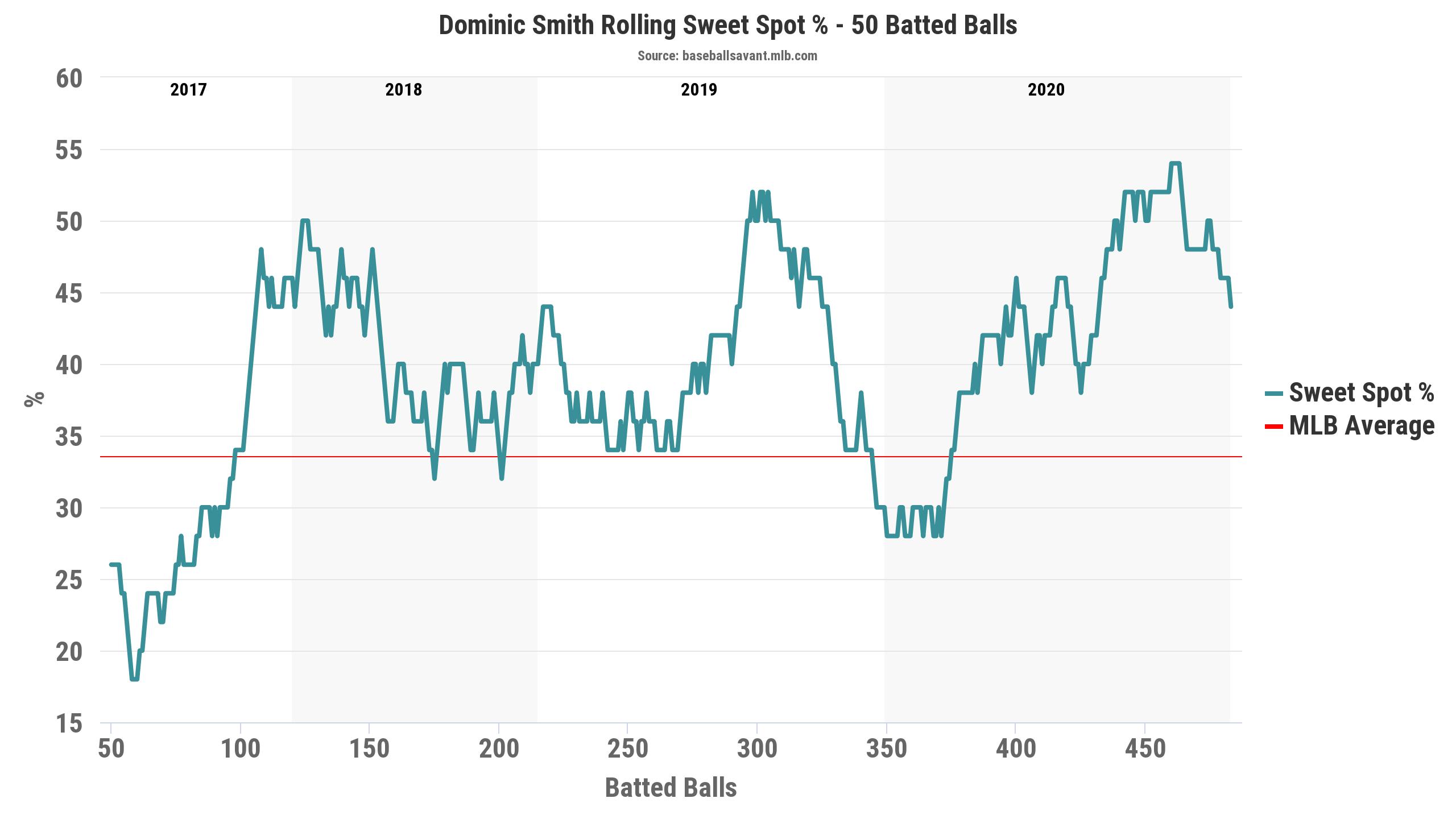

Curious if he is hitting the ball at ideal launch angles? Baseball Savant’s sweet spot rate measures how often a guy hits the ball at an ideal launch angle (8 to 32 degrees). Smith is doing that a lot more, too.

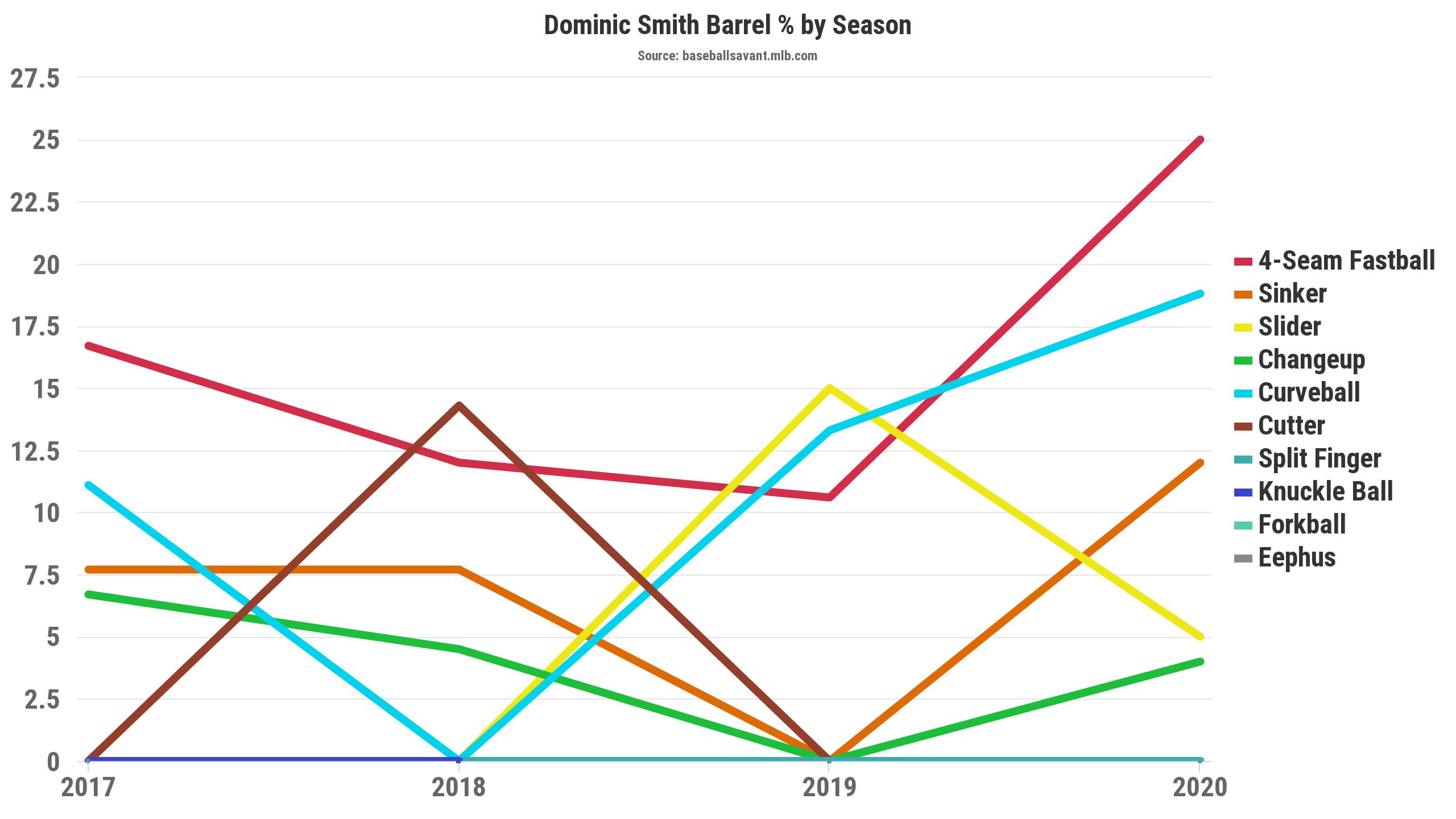

Putting those last two together, barrel rate measures how often a hitter hits a ball with an ideal combination of exit velocity and angle, and sure enough, Smith has seen his barrel rate increase from 7.4% in 2017-18 to 10.4% in 2019-20.

After a rough start to his career, Dominic Smith identified an issue, addressed the issue with a change in his approach, and saw a cascade of positivity. He made smarter, more targeted swing, he made contact on more of those swings, and he made harder contact when he made contact.

Dialing in on Zone 3

Let’s take a look at one particular zone where Smith seemed to make meaningful strides. Baseball Savant breaks down data by zones, and zone 3 is the corner of the strike zone up and in to left-handed hitters like Smith.

In 2017-18, Smith really struggled there. Across 44 pitches, he swung at 27, and put only seven in play. He totaled 20 strikes (14 called, 6 swinging). His average exit velocities were 84.3 and 86.4, respectively, and his average launch angles were 32 and 40. The statcast “sweet spot” metric measures contact with a launch angle between 8 and 32 degrees—once you get over 32 degrees, you get diminishing returns.

What does that look like? Beyond a lot of swing-and-miss, it’s mostly lazy fly balls. Here is a ball he hit in zone 3 in 2017 with launch angle 30 and exit velocity 84.2.

This mostly looks like a guy getting jammed – the pitch comes up and in, he manages to make contact, but it’s weak contact high in the air, and the left fielder retires him easily. The Statcast expect batting average on that contact was .033. With contact like that, his xwOBA in zone 3 those two years were .099 and .129.

Then Smith enters 2019 with his new stance and swing and his claim that he could “sit on that back hip and really reach and read the pitches now.” What happens in this zone, where he struggled so mightily before? Over 2019-20, he faced 49 pitches, swung at 32, and put 13 in play. He had 19 strikes (13 called, 6 swinging). The improvement in his ability to put balls in play is stark:

| Stat | 2017-18 | 2018-19 |

| Swing% | 61.4% | 65.3% |

| Contact% | 74.1% | 84.3% |

| Put in play per pitch | 15.9% | 26.5% |

| Put in play per swing | 25.9% | 40.6% |

| Strikes per pitch | .455 | .388 |

He also put the ball in play with more authority, with average exit velocity in 2019-20 of 89.7. His launch angles in zone 3 came down to a more productive space, too, with an average launch angle of 14 in 2019 and of 27 in 2020. Both are within that “sweet spot” range. How different is that 2019-20 contact from what we saw above? Here is a swing in zone 3 in 2019 with an exit velocity of 87.7 and launch angle of 16.

That ball wasn’t crushed, but you hit a ball on a line like that, good things will happen—the expected average on that one was .888.

And what about when he gets the exit velocity and launch angle up a bit?

That’s 105.7 exit velocity and launch angle of 27 and it’s an expected batting average of 1.000. The old Smith wasn’t really capable of that swing on that pitch in that zone.

Red Flags

Before we just call it a day and accept Smith as a star, we should look at a few possible concerns.

The most obvious is BABIP. After posting .254 BABIP for his first two years, Smith was at .344 over the last two. There are reasons to think Smith can keep carrying a high BABIP. In 2020, he was 8th in MLB with a 43% sweet spot rate, so he is hitting a lot of high-BABIP line drives. He was 36th in MLB with a 13.3% barrel rate. Steamer is projecting him for a .297 BABIP – basically regressing him to league average – but his ability to hit line drives and hit them hard is probably sufficient to keep his BABIP closer to where he was in 2019 (.320).

As Smith’s contact has improved, he has also pulled the ball more (42.5% in 2019-20 vs. 39.5% in 2017-18), and while that is not a huge number, it could make him more susceptible to the shift. The thing is, teams have already tried that. In his rookie year, he was shifted in 159 PA his first two years and 211 the next two. That could increase, but he isn’t pulling the ball so much that it’s a given and he has shown that he can hit through the shift, anyway.

Pitch type could also be an issue. While his barrel rate has increased overall with the change in approach, he made those strides against breaking balls and fastballs – his barrel rate vs. changeups is still very low.

Almost all of those lines are trending up. His barrel rate against sliders is trending down from 2019 but still up vs. 2017-18. Changeups, however, are down from where he was in 2017-18. Pitchers have not really adjusted to this, as he saw changeups 13.5% of the time his first two years and 12% the last two. Over those two years, among 342 players with 300+ PA, Smith faced the 134th highest rate of changeups. Pitchers could (and probably should) adjust to this by throwing him more changeups.

The thing is, I could see this as a positive. Smith doesn’t have to start crushing changeups. He wasn’t terrible against changeups last year (xwOBA of .306 vs. changeups was 59th out of 124 hitters with 25+ PA). But we’re also talking about a guy who identified a clear issue with his approach, developed a plan to solve it, executed the plan, and delivered results. That doesn’t mean he will make adjustments on changeups, but it suggests that he could.

The last issue is just sample size. It’s worth keeping in mind that we’ve been looking at four years of data, but it is just 728 career PA. The evidence we have after his swing change is 396 PA, which is less than 2/3rds of a season for a full-time player. Projections are going to be cautious on him and we probably should, too, simply because we just don’t know that much yet.

2021 Forecast

You remember that sentence, in the last paragraph, where I said we should probably be cautious? Well, we don’t always do what we should. Smith is exactly the type of player I look for in fantasy baseball. His performance has improved dramatically and it isn’t just noise. We have clear evidence that he actually improved (more contact, better contact) and we have a clear explanation for why that is happening (stance/swing change) and good reason to believe that can stick (he’s now displayed that swing the last two years).

I am not going to get crazy and start banking on drastic improvements vs. changeups or a BABIP that continues to rise. I expect his 2021 won’t reach quite the heights of his 2020. But looking at that 2019-20 combined? I mostly buy it. His .390 wOBA over that two-year stretch is 12th among 311 players with 350+ PA. His 149 wRC+ is tied for 10th. Correct the BABIP a bit and he settles in a bit lower – maybe more like a .350-.360 wOBA with a 120 wRC+. That’s far better than his projections.

The only question left for Smith is playing time. For the last few years, getting plate appearances hasn’t been a given for Smith, but this year I suspect he’ll enter the season with a clear everyday job.

If the designated hitter returns to the NL for 2021, this is a non-issue; Smith is a good enough hitter than having him and Alonso share 1B and DH is an easy choice. If not, the Mets almost have to keep using Smith in LF. He’s too good to bench and with Robinson Cano not playing this year, I expect McNeil will move back to 2B, allowing J.D. Davis to get out of the OF and play 3B, leaving Smith, Conforto, and Brandon Nimmo to patrol the OF. There is some risk that the Mets sign George Springer or another free agent, but even if they do, I expect Smith will play regularly.

Photo by Brian Rothmuller/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Doug Carlin (@Bdougals on Twitter)