It should come as no surprise that when it pertains to four-seamers, elevation is the name of the game. It feels like pitching coaches just blast U2 in team meetings when the topic of fastball location arises. “Listen to Bono,” Brewers pitching coach Chris Hook shouts to a nodding Josh Hader, “‘the goal is elevation.'” In 2020, the league collectively cranked that track up to 11, as no season in Statcast recorded history featured more elevated four-seamers:

| Season | ELFF% |

|---|---|

| 2020 | 26.3 |

| 2019 | 25.8 |

| 2018 | 24 |

| 2017 | 22.4 |

| 2016 | 19.1 |

This is likely for good reason. As has been thoroughly detailed in articles like this one from Jeff Zimmerman, elevating usually leads to strikeouts. With the focus on spin rates and rising fastballs, it would only make sense that the league would be trending in this direction.

If elevation is the name of the game, however, one would intuit that the league’s best heaters are indeed elevated. As it turns out, that’s not entirely true. Even more surprising? The location of some of the leagues best four-seamers are counter to where we’ve learned they “should” be.

“I Need You To Elevate Me Here”

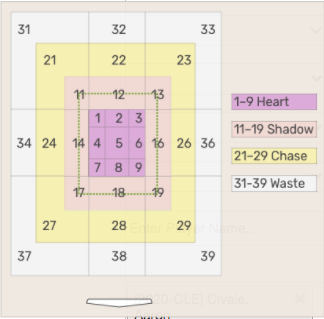

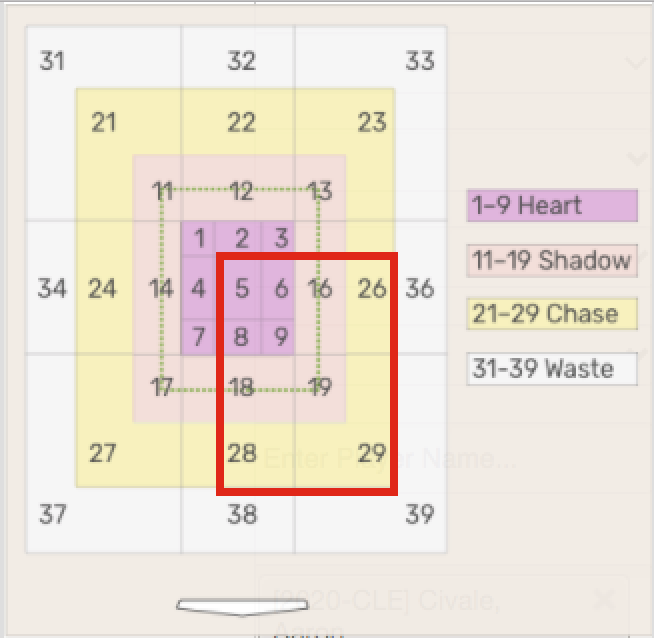

Before we begin, it’s important to explain how I’m defining elevated four-seamers (EFF). To me, EFF are thrown in attack zones 11, 12, 13, 21, 22 and 23 of the graphic below taken from Baseball Savant.

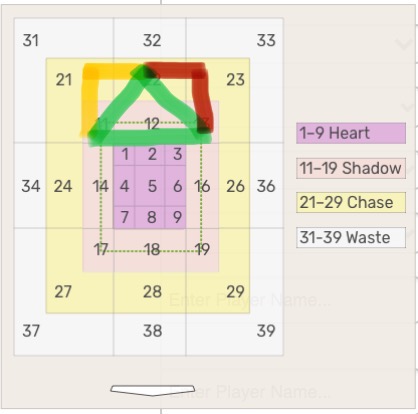

I heard valid arguments that zones 1, 2 and 3 should be included. A few pitchers told me they would only consider EFF to be those thrown in zones 11, 12, 13 and 22 while another sent me this very inventive graphic.

The point is: Elevation is a malleable term and while all of the arguments I heard were valid I decided to define elevation as just zones 11, 12, 13, 21, 22 and 23 as there seemed to be the most consensus there. For full transparency, it was easier for me to pull results by using these zones as opposed to using average Plate Z (a metric that shows the average vertical location of a pitch). Plate Z correlated highly to EFF% regardless of whether or not zones 1, 2 and 3 were included making it a moot point; whether I used plate Z, EFF with zones 1, 2 and 3 or without those zones, the results were the same.

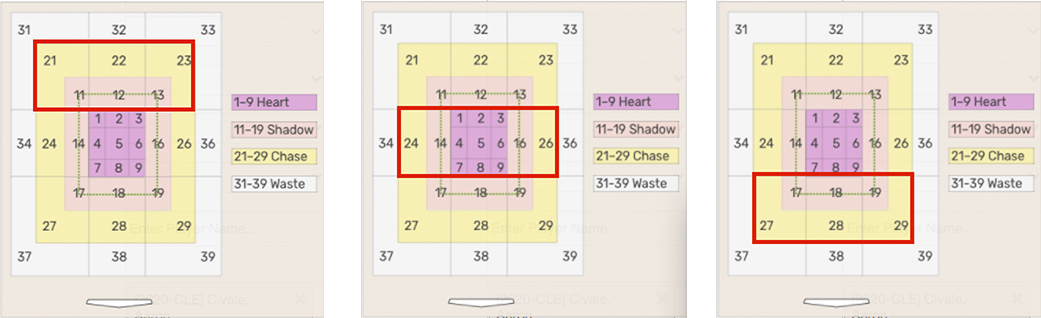

Let’s take a look at how each of those zones performed. We’ll group them into elevated, middle and low.

And the results:

| Zones | % | SwStr | CSW | wOBA | xwOBA | wOBAcon | xwOBAcon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevated | 26.3 | 16 | 22.9 | .290 | .279 | .346 | .322 |

| Middle | 54.7 | 10.7 | 35 | .352 | .345 | .410 | .402 |

| Low | 12.9 | 2.9 | 27.4 | .389 | .404 | .360 | .391 |

EFF return the highest SwStr, and the lowest wOBA, xwOBA, wOBAcon and xwOBAcon. The only category “elevated” doesn’t lead is CSW, which is no surprise considering “middle” is the only zone entirely in the strike zone. Let’s get even more granular and take a look at how every non-chase attack zone performs by the same metrics thanks to a great GIF from Nicholas Kollauf.

(If you’d like to mess around with this data yourself, you’re more than welcome to explore here. This particular dataset is in the Zones tab.)

In 2020, zone 12 was the only zone with a SwStr above 20% and recorded the lowest wOBA and xwOBA. The top three zones by wOBA and xwOBA were elevated (11, 12 and 13). The top zone by wOBAcon and xwOBAcon (when we adjust the minimum to 100 BIP) was elevated (zone 22). It is interesting to note that when we sort by SwStr, zones 2, 3, and 1 immediately follow zone 12. That’s of great benefit to the pro “zones-1-2-3-are-elevated!” crowd. While I’m still going to exclude those zones from the “elevated” queries featured below, I’ll get to why it’s all moot later on.

For now, the important takeaway is we’ve provided ample evidence that confirms what Zimmerman and others have written about and what seems to be a golden rule: if you’re going to throw heat, you should elevate it.

So let’s take a look at those who elevated the most (min 150 FF thrown) and how they fared.

“The Goal is Elevation”

In order to make the EFF data a bit more palatable, I made it league adjusted; an EFF+ of 120 means this pitcher threw EFF 20% more than league average. Once again for transparency sake, there is minimal change if I supplant EFF with Plate Z or add zones 1, 2 and 3 to EFF.

These are pitchers that (min 100 EFF thrown) elevated more than 30% above league average.

| Pitcher | EFF+ | wOBA_All | xwOBA_All | SwStr_All |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grant Dayton | 193 | .283 | .297 | 16.7% |

| Freddy Peralta | 174 | .244 | .248 | 17.3% |

| James Karinchak | 167 | .233 | .228 | 19.6% |

| Josh Hader | 167 | .345 | .301 | 15.9% |

| Blake Snell | 155 | .444 | .409 | 11.3% |

| Trevor Richards | 155 | .367 | .346 | 8.9% |

| Brent Suter | 152 | .256 | .269 | 16.8% |

| Robbie Erlin | 150 | .378 | .329 | 8.2% |

| Madison Bumgarner | 141 | .378 | .443 | 3.6% |

| Pete Fairbanks | 141 | .339 | .307 | 16.4% |

| Tyler Mahle | 140 | .333 | .304 | 14.3% |

| Taijuan Walker | 138 | .292 | .358 | 9.8% |

| Tyler Matzek | 138 | .281 | .236 | 15.1% |

| Luis Castillo | 137 | .377 | .296 | 17.3% |

| Max Fried | 137 | .287 | .280 | 10.6% |

| Cristian Javier | 136 | .309 | .297 | 9.1% |

| Jordan Lyles | 134 | .434 | .394 | 3.9% |

| Daniel Ponce de Leon | 133 | .357 | .337 | 18.2% |

| League Average | 100 | .338 | .333 | 10.9% |

This is a hodgepodge of names that feature really good four-seamers (James Karinchak), four-seamers that may not have been as good as people thought (Blake Snell) and really bad four-seamers (Madison Bumgarner). When I first saw this I was a little surprised. I didn’t expect there to be a perfect correlation between elevated four-seamers and fastball success but I was expecting to see a bit higher correlation than 0.125 (more on this later). Perhaps the results would be better if we didn’t look at how the overall FF performed but focused in how just EFF performed.

| Pitcher | EFF+ | wOBA_EFF | xwOBA_EFF | SwStr_EFF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grant Dayton | 193 | .273 | .291 | 19.5% |

| Freddy Peralta | 174 | .204 | .174 | 25.3% |

| James Karinchak | 167 | .224 | .183 | 21.4% |

| Josh Hader | 167 | .306 | .324 | 16.4% |

| Blake Snell | 155 | .461 | .360 | 12.2% |

| Trevor Richards | 155 | .380 | .300 | 13.4% |

| Brent Suter | 152 | .141 | .167 | 25.2% |

| Robbie Erlin | 150 | .283 | .248 | 13.9% |

| Madison Bumgarner | 141 | .340 | .452 | 5.9% |

| Pete Fairbanks | 141 | .207 | .229 | 20.2% |

| Tyler Mahle | 140 | .395 | .328 | 20.3% |

| Taijuan Walker | 138 | .203 | .284 | 13.9% |

| Tyler Matzek | 138 | .300 | .267 | 22.2% |

| Luis Castillo | 137 | .255 | .226 | 25.0% |

| Max Fried | 137 | .312 | .344 | 14.8% |

| Cristian Javier | 136 | .197 | .237 | 13.5% |

| Jordan Lyles | 134 | .512 | .434 | 5.9% |

| Daniel Ponce de Leon | 133 | .264 | .275 | 21.0% |

| League Average | 100 | .283 | .274 | 16.0% |

Even when we’re just looking at how those EFF performed, the results aren’t great. Hader actually performed worse on his elevated his four-seamers, as did Max Fried and Tyler Mahle. Some four-seamers did perform better when elevated — Luis Castillo’s FF went from a .377 wOBA overall to a .255 when elevated — but the same pattern emerged: just because guys were elevating a lot didn’t mean they were having success.

What if we try this the opposite way. Instead of sorting by those who elevated the most, let’s sort by those who had the most success. The following are those who had a sub .275 wOBA/xwOBA along with a -5 run value or lower on their fastball (for those unfamiliar with run value).

| Pitcher | EFF+ | wOBA_All | xwOBA_All | RV_All |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenta Maeda | 68 | .101 | .145 | -5 |

| Nick Anderson | 153 | .137 | .259 | -7 |

| Brent Suter | 152 | .256 | .269 | -6 |

| Trevor Rosenthal | 108 | .214 | .197 | -10 |

| Walker Buehler | 100 | .165 | .199 | -10 |

| Mike Fiers | 124 | .252 | .259 | -7 |

| John Means | 115 | .249 | .201 | -5 |

| Trevor Bauer | 126 | .224 | .223 | -11 |

| Drew Pomeranz | 147 | .224 | .232 | -7 |

| Chad Green | 81 | .200 | .237 | -8 |

| Jacob deGrom | 114 | .239 | .244 | -8 |

| Shane Bieber | 85 | .249 | .267 | -7 |

| Justin Wilson | 84 | .221 | .263 | -6 |

| Freddy Peralta | 174 | .244 | .248 | -7 |

| Caleb Thielbar | 75 | .257 | .270 | -6 |

| Liam Hendriks | 73 | .216 | .269 | -8 |

| J.B. Wendelken | 43 | .242 | .248 | -6 |

| Blake Taylor | 99 | .216 | .249 | -10 |

MLB’s best fastball by wOBA belonged to Kenta Maeda who elevated his heater 32% below league average. The best fastball by run value belonged to Trevor Bauer who had an EFF% 26% higher than league average. Walker Buehler had arguably the best overall fastball (only heater with a sub .200 wOBA and xwOBA and RV of -10 or less) and he threw it … well that’s interesting. According to the current definition of EFF we’re using, he elevated exactly at league average. Once again, we see no definitive pattern between success and elevation.

Let’s do one final zoom out and take a look at how every single pitcher did who threw at least 150 heaters.

Data Visualization by @Kollauf on Twitter

There is a very minimal relationship between an individual pitchers EFF% and success.

This isn’t entirely fair, however.

First and foremost, with each fastball comes a swath of different variables like pitcher talent level, count utilization, and more. Also, correlation doesn’t imply causation. Just because a pitcher elevates his four-seamer above or below league average doesn’t firmly mean that four-seamer is good or bad, there are far more factors that come into play.

This piece is not about being iconoclastic. I’m not aiming for every pitcher to stop elevating, there’s plenty of data that shows that it works. Instead, it’s about answering that question that’s been nagging me for weeks now. A question that this data only seems to make more pressing:

If elevating FF is beneficial, then why do many of the best pitchers in the majors elevate so infrequently?

“Going Down, Excavation”

Walker Buehler. Shane Bieber. Kenta Maeda. Yu Darvish, Sonny Gray. Zac Gallen, Aaron Nola, Liam Hendriks. Sounds like a pretty ideal fantasy staff? It also happens to be just some pitchers who had above average results on their fastball in 2020 while elevating less than league average.

How are they doing it?

Let’s try to figure that out by looking at some of the best individual non-elevated four-seamers and how they in particular had success.

Walker Buehler

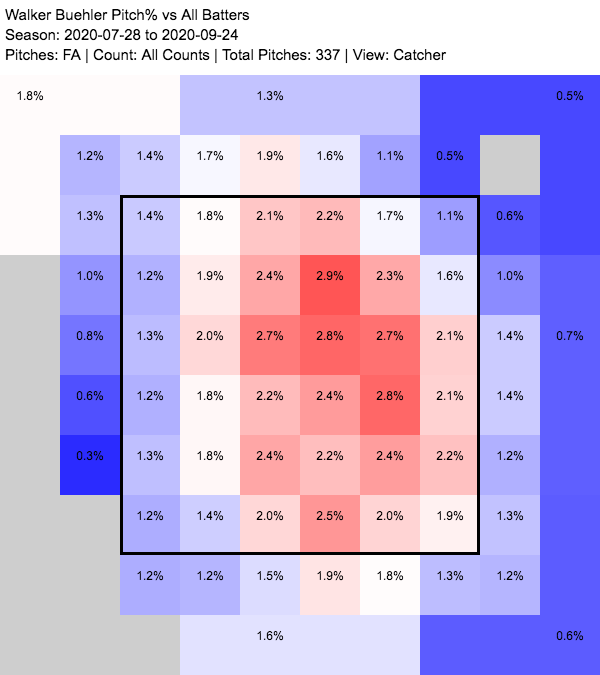

Earlier on, I said that Walker Buehler threw a league average amount of EFF. That isn’t necessarily true. As a reminder, we’re defining EFF as those in zones 11, 12, 13, 21, 22 and 23. If we change that definition to include zones 1, 2 and 3 or if we define elevation by plate Z (both of which were valid ways of interpreting ‘elevation’), Buehler actually throws a below league average amount of EFF. Overall, this is what Buehler’s four-seamer heat map looked like according to Fangraphs.

That’s a lot of four-seamers over the heart of the plate. A location that actually did wonders for him. Buehler put up a -14 run value over the heart of the plate. That led the league by a relatively considerable margin.

If we want to get more specific, Buehler threw 51.4% of his four-seamers here:

He also fared incredibly well there both to righties and lefties in that location:

| Metric | RHB | LHB |

|---|---|---|

| % of FF | 63.8 | 45.6 |

| CSW | 39.2 | 37.2 |

| SwStr | 5.2 | 1.3 |

| wOBA | .164 | .314 |

| xwOBA | .240 | .289 |

| wOBAcon | .145 | .296 |

| xwOBAcon | .264 | .251 |

Buehler got an absurd amount of called strikes against RHB/LHB in this part of the zone. He also minimized damage on these four-seamers incredibly well. League average wOBAcon on four-seamers thrown by RHP to RHB in this part of the zone is .430, almost 300 points higher than Buehler’s! This doesn’t mean that Buehler never elevates. As you can see below, if he’s going to elevate, he’s doing it in two-strike counts.

https://gfycat.com/colorlessfreshchuckwalla

So how does Buehler have so much success low? One reason may be his elite curve. Here’s an overlay of Buehler’s FF/KC mix.

https://gfycat.com/satisfiedlatedingo

Showing one example that features two pitches tunneling well doesn’t mean that it happens all the time, but it can give us a good idea as to how well pitches can tunnel (though Buehler seems to do this often). Coincidentally, the fastball featured here was the first pitch of the AB while the curve — and that terrible swing — was two pitches later. Charlie Blackmon came into this game slashing .424/.463/.606. Poor guy. Meanwhile, Buehler’s curve ended the season with a 42% strikeout rate, the highest of his career.

Another reason could be because of the location of Buehler’s other two strikeout pitches. While the strikeout rates of Buehler’s sinker (22.2%) and cutter (17.9%) are 3rd and 4th respectively in his arsenal, they’re actually 1st and 2nd when it comes to Put Away Rate (a sort of efficiency metric; or how often a pitcher converts a two-strike count into a strikeout with a particular pitch).

| Pitch | % Thrown | K% | PAR% |

|---|---|---|---|

| FF | 54 | 36.2 | 24 |

| CB | 16 | 42.1 | 23.5 |

| FC | 14 | 17.9 | 25 |

| SI | 9 | 22.2 | 40 |

| SL | 7 | 5.9 | 4.3 |

The sinker had a 40% Put Away rate, which led the league (holy small sample size, Batman) while the 25% Put Away rate was top-20 among starters. While Buehler didn’t overtly lean on these pitches for Ks, he was very efficient with them in two-strike counts.

We cannot definitively say that Buehler’s curve, cutter and sinker excelled in various ways because of his lower EFF%. I feel certain, however, that we can say that they all served to benefit one another very well.

I could fill an entire article postulating the exact ‘why’ Buehler has success with his non-elevated four-seamer, but it’d still be secondary to the fact that whatever that “why” may be, he has success. Let’s take a look at a different use case now featuring a pitcher who elevates his heater even less but also throws fewer four-seamers.

Kenta Maeda

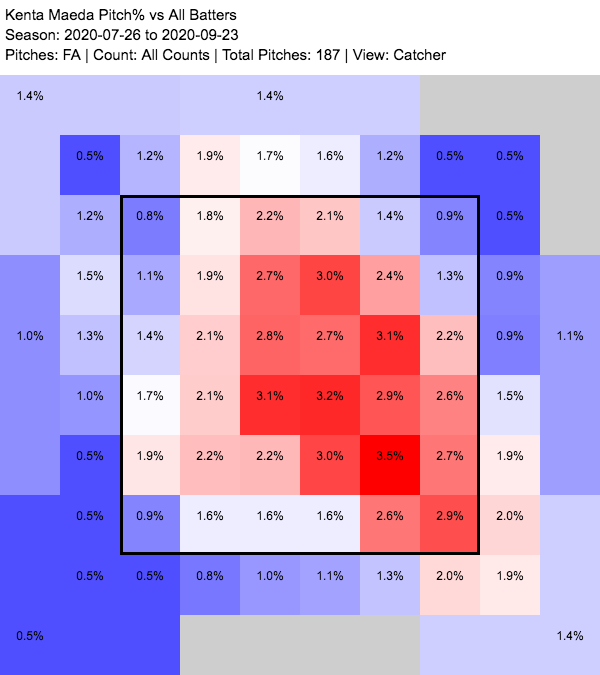

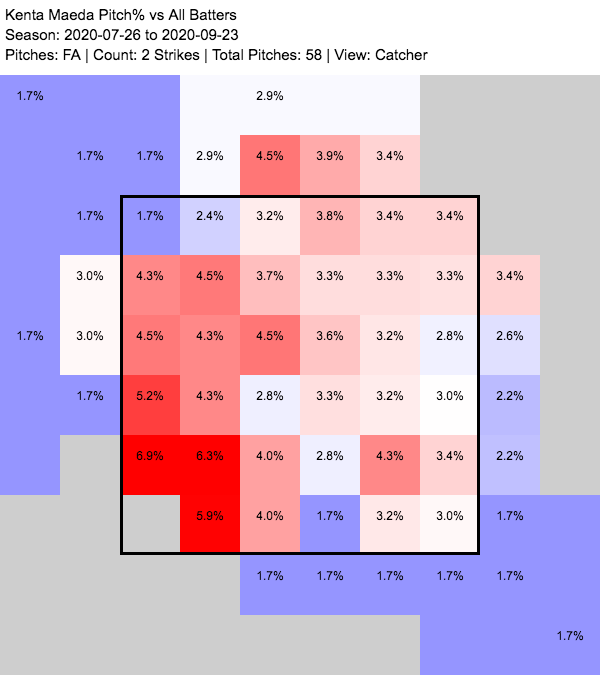

Maeda’s four-seamer was absolutely fantastic in 2020. While he only threw the pitch 19% of the time, it was incredibly effective for him. It posted a .101 wOBA and a .156 wOBAcon meaning batters rarely hit it and when they did, they didn’t do much with it at all. The pitch also posted a near-league average 10% SwStr with a league leading (among SPs) 37% CSW rate. Yet, when it came to location, Maeda elevated his four-seamer 32% less than league average, instead opting to go lower.

Over 65% of Maeda’s four-seamers were thrown either in the heart of the zone or lower. Whereas Buehler would either elevate with two strikes or rely on his curve for a majority of his strikeouts, Maeda did the opposite. His highest pitch by K% was his four-seam at 43%. And where did he put those heaters? A lot of the time, he put them pretty low:

The heater wasn’t Maeda’s only pitch with a K% over 40%, however, as his splitter/changeup (depending on the website) picked up a 40.4% strikeout rate, too.

Here’s an overlay of his FF/CH in action:

https://gfycat.com/sphericalthisekaltadeta

Look at how insanely well those two pitches tunnel at the point in which the batter needs to commit.

While the off-speed and four-seam picked up the lion’s share of the strikeouts in ’20, that doesn’t mean the rest of the arsenal didn’t help bolster those pitches. Here’s an overlay of his entire arsenal in action.

https://gfycat.com/dangerouscolorfulindochinesetiger

Let’s take a look at where all of these pitches are close to a batters commit point and where they end up.

An important caveat regarding this particular overlay (and almost all overlay’s, to be honest): It doesn’t suggest that Maeda does this all the time. This overlay is a veritable Frankenstein’s monster taken from different at-bats and is not meant to suggest that Maeda tunnels this effectively with every pitch. It’s merely meant to show the ceiling of Maeda’s tunneling abilities featuring the locations Maeda most often throws to. With all that said, this is absolutely remarkable.

As was true with Buehler, we can’t definitively say that tunneling is the lone reason why Maeda has success with lower four-seamers but we can say he’s yet another example of someone who has success by not elevating.

We’ve now looked at two starting pitchers that feature prominent breaking/off-speed pitches in their arsenal but seemingly benefit from lower four-seamers. Let’s end on the other side of the spectrum; with someone who throws a lot of four-seamers and not too much else.

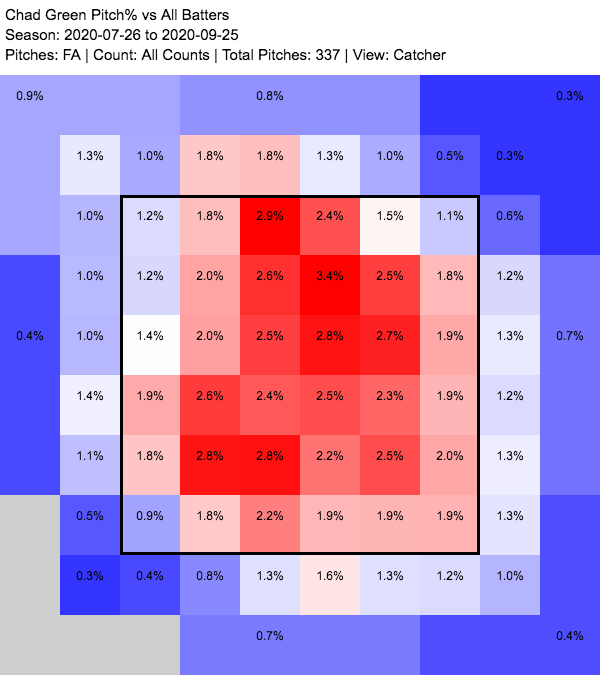

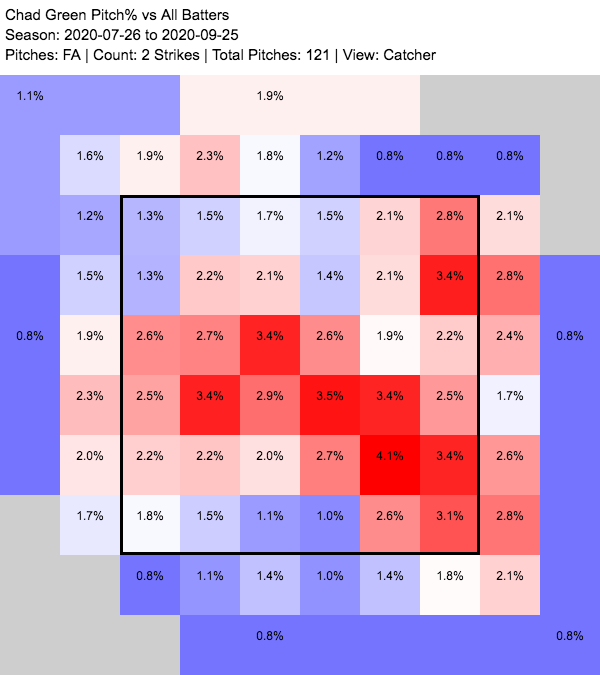

Chad Green

Green was the only pitcher in baseball that threw four-seamers over 70% of the time, had a higher K% on their four-seamer than any other pitch type, and had a wOBAcon below .300 on that heater. That seems like a lot of qualifiers, so let me put it another way: Chad Green leaned on his four-seamer a lot, yet it was still his go-to strikeout pitch, and batters couldn’t do much with it when they put it in play. He also happened to elevate his four-seamer 29% below league average, instead focusing on the heart of the plate or lower.

| % | SwStr | wOBA | xwOBA | BIP | wOBAcon | xwOBAcon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 58.6 | 12.5 | .214 | .255 | 30 | .291 | .360 |

| RHB | 65.3 | 14.3 | .228 | .249 | 15 | .325 | .364 |

| LHB | 52.4 | 10.5 | .199 | .262 | 15 | .259 | .356 |

There are a lot of numbers here, so let me clarify. 58.6% of the four-seamers Green threw were in the middle of the zone or lower, with 65% of the four-seamers he threw RHH ending there, too. The league average wOBA and xwOBA in these zones is .357/.353 while the wOBAcon/xwOBAcons are .410 and .406. The league average SwStr? 8%. I think it’s safe to say that, when we’re not count-dependent, Green has a lot of success with non-elevated four-seamers. I mention count as things looked a bit different for Buehler when we factored that in, so let’s do the same for Green.

| % | SwStr | wOBA | xwOBA | BIP | wOBAcon | xwOBAcon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 55 | 13.3 | .226 | .231 | 14 | .401 | .402 |

| RHB | 67 | 15.2 | .241 | .251 | 9 | .409 | .433 |

| LHB | 45 | 11.1 | .202 | .197 | 5 | .388 | .374 |

Count be damned, when it came to four-seam fastballs, Green wasn’t elevating all that much. He had very good SwStr both against RHH and LHH and while batters were able to do some damage, the sample size wasn’t all too large.

Location aside, there is nothing remarkable about Green’s fastball. The Bauer Units are 5% above league average. He gets 4% more extension than league average, the velocity is in the 84th percentile — good not elite — and he gets 16% more rise than average. Although Green was not a top-10 reliever in baseball last year by FIP, SwStr, or K% he was in the top 5% of the league or better in xBA (.161), wOBA (.218), xwOBA (.221), xwOBAcon (.294), HardHit% (26.7) and xERA (2.20) That’s a lot of success for a pitcher to have who elevates nearly 30% less than league average.

“Explain All These Controls”

Buehler, Maeda, and Green are just three specific examples of those having success without elevating. Here is a full list of those who have had better than league average wOBA/xwOBA’s on four-seamers despite elevating them below league average.

| Pitcher | EFF+ | wOBA_All | xwOBA_All | CSW_All |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tyler Rogers | 14 | .256 | .218 | 34.7% |

| Taylor Widener | 39 | .314 | .315 | 35.6% |

| J.B. Wendelken | 43 | .242 | .248 | 34.0% |

| Pablo Lopez | 63 | .303 | .298 | 34.0% |

| Kenta Maeda | 68 | .101 | .145 | 37.3% |

| Kyle Zimmer | 70 | .272 | .275 | 34.1% |

| Zac Gallen | 72 | .255 | .295 | 33.9% |

| Liam Hendriks | 73 | .216 | .269 | 33.2% |

| Tanner Rainey | 73 | .272 | .308 | 34.6% |

| Brad Boxberger | 74 | .321 | .312 | 32.0% |

| Caleb Thielbar | 75 | .257 | .270 | 33.7% |

| Javy Guerra | 77 | .320 | .266 | 30.7% |

| Jake Diekman | 81 | .192 | .295 | 38.6% |

| Chad Green | 81 | .200 | .237 | 34.4% |

| Sonny Gray | 82 | .322 | .271 | 32.4% |

| Tyler Duffey | 84 | .209 | .221 | 37.7% |

| Justin Wilson | 84 | .221 | .263 | 35.2% |

| Matt Foster | 84 | .226 | .305 | 32.9% |

| Shane Bieber | 85 | .249 | .267 | 35.4% |

| Keegan Akin | 85 | .285 | .318 | 31.3% |

| Jake McGee | 86 | .240 | .234 | 33.4% |

| Yu Darvish | 87 | .208 | .146 | 32.9% |

| Archie Bradley | 88 | .275 | .328 | 35.2% |

| Hector Neris | 90 | .322 | .325 | 32.4% |

| Austin Gomber | 90 | .236 | .314 | 29.3% |

| Nick Wittgren | 90 | .227 | .285 | 31.1% |

| Aaron Nola | 92 | .222 | .284 | 33.8% |

| Edwin Diaz | 95 | .319 | .252 | 36.4% |

| Kolby Allard | 97 | .313 | .318 | 33.6% |

| Frankie Montas | 98 | .239 | .225 | 30.6% |

| Walker Buehler | 100 | .165 | .199 | 35.0% |

So, what do all of these pitchers have in common? What is the major through line that allows them to have success with non-elevated four-seamers?

There isn’t one. At least as it pertains to the four-seamers themselves. The successful non-elevated heaters don’t all get more rise than elevated heaters. They don’t all have similar tilt. They don’t have similar amounts of extension or Bauer Units or active spin or vertical or horizontal movement. It should be said however, that Alex Chamberlain may be onto something with his magnificent work regarding attack angle.

In order to find something more tangible, we need to look elsewhere. We established from all of the above examples that pitchers that have success with non EFF tunnel well, but that’s a bit nebulous. There are plenty of guys who do elevate that tunnel just as effectively. I asked Zac Gallen how he was able to have so much success by not elevating and he said, “being down definitely helps my cutter and changeup, but on the flip side, the fastball up will help my curveball.” This makes a lot of sense for a curveball like Gallen’s but may not necessarily be the case for Bieber or Buehler’s curveballs, both of which get more vertical movement. Also, a consistent, go-to tunneling metric is yet to be developed so saying pitches tunnel well, at least for the time being, is a bit subjective.

Tunneling aside, there is a valid, more concrete argument to be made that what makes these non-elevated four-seamers so effective has nothing to do with the four-seamers themselves but what is in the rest of the arsenal. Curious about who had the best results immediately preceding a non-elevated four-seamer, I reached out to Justin Filteau, a fantastic data analyst here at Pitcher List. Filteau pulled the SwStr, wOBA/xwOBA and wOBAcon/xwOBAcon for every pitch after a non-elevated four-seamer.

This is going to be a mouthful so I apologize. Here is a list of the 15 pitches that were thrown after non-elevated four-seamers that returned a better-than-average SwStr, CSW, wOBA and xWOBA (min 50 thrown). Also, if you’d like to sort this data yourself, it’s available for you here underneath the PostLowFF tab.

| Pitcher | Pitch Type | Thrown | BIP | SwStr | CSW | wOBA | xwOBA | wOBAcon | xwOBAcon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shane Bieber | KC | 51 | 5 | 31.4% | 33.3% | 0 | .104 | 0 | .126 |

| Gerrit Cole | SL | 57 | 10 | 26.3% | 28.1% | .261 | .297 | .261 | .315 |

| Kevin Gausman | FS | 87 | 9 | 24.1% | 29.9% | .097 | .124 | .097 | .151 |

| Brandon Woodruff | FF | 56 | 10 | 23.2% | 32.1% | .174 | .122 | .174 | .126 |

| Ian Anderson | CH | 52 | 4 | 23.1% | 34.6% | 0 | .160 | 0 | .168 |

| Chris Paddack | CH | 68 | 16 | 22.1% | 30.9% | .284 | .291 | .284 | .315 |

| Jose Cisnero | FF | 67 | 11 | 20.9% | 34.3% | .269 | .279 | .269 | .301 |

| Lance Lynn | FC | 58 | 9 | 20.7% | 31.0% | .135 | .218 | .135 | .224 |

| Cristian Javier | SL | 51 | 6 | 19.6% | 31.4% | .145 | .064 | .145 | .067 |

| Brent Suter | FF | 77 | 20 | 19.5% | 31.2% | .296 | .242 | .296 | .248 |

| Walker Buehler | FF | 140 | 12 | 19.3% | 43.6% | .145 | .184 | .145 | .196 |

| Drew Pomeranz | FF | 63 | 5 | 19.0% | 31.7% | 0 | .124 | 0 | .127 |

| Taylor Clarke | SL | 54 | 9 | 18.5% | 38.9% | .232 | .222 | .232 | .228 |

| Mike Minor | FF | 94 | 16 | 16.0% | 33.0% | .109 | .154 | .109 | .174 |

| John Means | FF | 70 | 6 | 14.3% | 35.7% | 0 | .164 | 0 | .165 |

That Shane Bieber is … pretty good, huh. The AL Cy Young winner threw 51 knuckle-curves immediately after non-elevated four-seamers. They collectively returned a wOBA of zero and a 31.4% SwStr. There are a few other impressive standouts, too. Our old friend Buehler is there but with his four-seamer which returned an impeccable 44% CSW. There’s also Kevin Gausman, who elevated four-seamers 16% below league average and returned a .097 wOBA and wOBAcon on his post non-elevated four-seam splitter, and two exciting changeups from Ian Anderson and Chris Paddack.

“It’s OK to Be Uncool”

There’s another finding from the data Filteau provided me that begets an important question I feel many reading may be asking: Would pitchers that didn’t elevate be better if they did?

The third-best pitch by SwStr thrown after a non-elevated four-seamer was Jack Flaherty’s SL with a 31%. In more laymen’s terms, Flaherty got a lot of whiffs on his SL when he threw it after a non-elevated four-seamer. Overall, Flaherty threw 49% fewer elevated four-seamers than league average. He rarely went up with his four-seamer and the results of the pitch were just fine. The .323 wOBA is about league average but the .515 xwOBAcon is a blemish. If Jack Flaherty’s non-elevated four-seamers are aiding to set up what is arguably the best pitch in his arsenal, should he change the approach?

Let’s use a different example focusing on a guy who has definitive success with his four-seamer: Bieber. If you’re Cleveland pitching coach Carl Willis, are you honestly going to tell Shane Bieber to try and elevate his four-seamer more knowing what you know about his knuckle-curve results? If you’re Mark Prior, are you going to tell Buehler, who posted unarguably a top-3 fastball in baseball last year, that he should change what he’s doing? To reconfigure the approach he’s using and already having immense results with for the chance that it may get even better? Likely not worth the risk.

There is one final question that this data brings up that we haven’t quite addressed. One that, sadly, may provide just as intangible of an answer as the “how” or “why” did but is of an endless interest to me all the same: What, if anything, does this mean for the future of pitching?

“Maybe You Could Educate My Mind”

The game theory of baseball is really exciting to me. Trying to find evidence of micro shifts in baseball strategy and how they may lead to macro shifts is a big motivator for why I do research. What is the next market inefficiency? How will hitters keep up with pitchers and vice versa? Can you tell I don’t have many friends?

If the percentage of elevated four-seamers has been increasing every year since 2015, then when will the bubble burst? Are organizations like the Dodgers and Indians trying to get ahead of that curve or is it coincidence that there are more than a handful of successful non-EFF? Only time will give us the answers to these questions but I think there may be some tea leaves that we can look at involving those guys always trying to end pitchers’ careers: hitters.

If batters are adjusting to elevated four-seamers, then pitchers will likely need to get away from throwing them so frequently. One way to see if batters are adjusting would be to look at the attack angle of their swing. This is taken from an article by Bahram Shirazi at Rockland Peak Performance: “Attack Angle is the angle of the bat’s path, at impact, relative to the horizontal. A positive value indicates swinging up when bat meets the ball, and a negative value indicates swinging down, and zero is perfectly level.” If the league average attack angle is beginning to flatten, you could make a case hitters were trying to get to the pitches that often prove to be their kryptonite. Sadly, however, there is no publicly available information on hitters’ attack angle. I’d need to try something different.

I thought I may be able to find something if I looked at who had the most success against EFF.

| Name | wOBA |

|---|---|

| Freddie Freeman | 1.161 |

| Aaron Hicks | .853 |

| Dylan Moore | .701 |

| Jake Cronenworth | .698 |

| David Bote | .692 |

| Kyle Tucker | .620 |

| Tim Anderson | .599 |

| Matt Chapman | .594 |

| Justin Smoak | .591 |

| DJ LeMahieu | .590 |

| Jacob Stallings | .581 |

| Will Smith | .560 |

| Corey Seager | .550 |

| Jesus Aguilar | .549 |

| Andrew McCutchen | .536 |

Freddie Freeman is a fastball hitting machine. High. Low. Wherever it was, he usually crushed it. I posted about this on Twitter which led me to having a discussion with Driveline hitting intern and Freddie Freeman enthusiast Noah Thurm.

I asked Thurm about attack angle and whether or not he felt attack angles were beginning to flatten. After acknowledging that the data wasn’t publicly available and there’s a large reliance on modeling and approximating, Thurm responded, “Not quite — at the league-wide level attack angle is still [steepening], but a growing number of hitters are taking some out situationally, primarily with two strikes.” Thurm mentioned that guys like Randy Arozarena, Freeman and Mike Yastrzemski have been “feasting with two strikes by employing a flatter path optimized for high FB.” I questioned whether he saw league average attack angle flattening in the future and Thurm said, “Yes, I think major league hitters should/will continue to develop a differentiated skillset by count/game state.” Essentially, there could be an increase in the amount of hitters we see who are able to make necessary swing path tweaks mid at-bat. Fun if you’re a hitter, terrifying if you’re a pitcher who overtly relies on elevated heat.

I can’t say for certain that everyone on the above list is developing that differentiated skillset that Thurm talks about but, thanks to Al Leiter, we can say it about Corey Seager.

Lands the line well, hit all locations everywhere. Timing and gives himself a shot to do multiple things. Get there and the pitch will tell you what to do.

Al Leiter breaks down Corey Seager's hitting approach https://t.co/Grnq363Yrs #MLBFilmRoom via @MLB

— Craig Hyatt (@HyattCraig) December 20, 2020

The bubble may not burst in 2021 or 2022, but when it does, I don’t think it will look how we think. Elevated four-seamers won’t fully go away even when league averages begin their inevitable downturn. Instead I think elevated four-seamers will become just another tool in a pitcher’s tool belt. It may not be one they go to as frequently, but it will be just as dangerous when utilized.

“Elevation”

Pitching is a language. Anyone who has ever tried to learn a language knows that for every foundational rule, there is an exception to that rule. The exception may be fully counter to what the foundational rule is but both are true all of the same. One of the current foundational rules is that pitchers should be elevating heat in order to optimize success. An exception to that rule may be that pitchers don’t need to elevate their heat to optimize success. We’re left with a sort-of baseball Schrödinger’s cat in which both things are true.

The point of this piece is not to say that pitchers should stop elevating their four-seamers. Instead, it’s to provide ample evidence that there is more malleability than we think when it comes to four-seamer location. A pitcher dotting the heart of the plate or the bottom of the zone with four-seamers does not mean that four-seamer is ineffective or needs to seek a new location. When we see a strike zone plot filled with middle/low four-seamers, we can’t simply write off that performance as poor or one in which a fastball should have been elevated more (and I am fully speaking to myself here). Those four-seamers could have been more about a preceding change-up or the upcoming curveball that’s about to get bounced.

While the game is high-heat focused, it will adapt. Batters will start to incorporate swings with flatter attack angles into their arsenal and, when they do, things are going to change. Or, if you believe Zac Gallen, that might not even matter. “Nothing in the past, present, or future of the game was/will be better than a dotted [fastball] down and away,” Gallen said to me. “It doesn’t matter if swing planes stay the same or go back to normal, a [fastball] on the black down and away is so tough to pull the trigger on.”

Swing change or not, whatever happens in the future, it looks like Gallen, Bieber, Buehler and more will be ready.

Photos by Jon Bleiweis/Wikimedia Commons/flickr and Frank Jansky/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Doug Carlin (@Bdougals on Twitter)

Awesome article. Gallen’s comments remind of how brilliant the intuition of traditional pitch callers’ is.

The one thing that excites me is that team’s will have a much more advanced idea of attack/approach angle going forward after the implementation of Hawk-Eye across the league. The exciting limb tracking feature includes bat path data as well. The more data these teams get their hands on, the more they will begin to shift their strategies depending on the pitcher and batter combination. Once the public gets their hands on approach/attack angle and Vertical Bat Angle, there is going to be a plethora of research opportunity!

Very insightful. Love the two pitch data of what is most effective for each pitcher after throwing the fastball down. This is a one pitch at a time game based on how you threw the current pitch, how the hitter reacted to that pitch, & where you think the hitter is going on the next pitch. Absent of that, the outcome results on what happens to the next pitch after you throw a particular pitch or to a particular location is certainly meaningful.

jw