José Ramírez has been a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Nobody really knows what to do with him. And rightly so. He was a first-round, oft-top three pick who’s underperforming to an extreme degree. You invested so heavily that you can’t just drop him. You don’t want to sell low on him given that investment, and no one will pay a satisfying price for him because he’s been so bad.

I have him on a team. I feel your pain. Day in and day out, 0-5, 1-4, no counting stats, nothing. He’s ruining your team’s batting average and giving you some stolen bases without any power in return. But if you wanted that, you would have drafted Billy Hamilton 14 rounds later!

I’ve seen all kinds of takes on Ramírez’s slow start. Buy low. Regression’s coming. And flat out concern.

Still, no one has yet to figure out what’s actually wrong with Ramírez. Let’s change that.

First, I’ll dive into his batted-ball data and plate discipline to see if something’s really changed or he’s simply due for regression. Next, I’ll examine what made Ramirez successful early last season and what’s holding him back this season.

Batted-Ball Profile

| Year | R | HR | RBI | SB | AVG | OBP | SLG | BABIP |

| 2018 | 110 | 39 | 105 | 34 | .270 | .387 | .552 | .252 |

| 2019 | 11 | 1 | 5 | 5 | .157 | .237 | .229 | .171 |

To date, Ramírez has been atrocious. The first thing that jumps out to me is Ramírez’s .157 batting average and .171 BABIP. His BABIP is literally half the .318 and .312 marks he posted in 2017 and 2016, respectively. It’s simply unsustainable for a hitter spraying the ball to all fields (career-high 31.0 Oppo% and 39.4 Cent%), hitting an above-average amount of line drives (22.9%), with good speed, and producing an above-average amount of infield hits (14.3%).

Ramírez does hit a lot of fly balls, however. His current 47.1 FB% would put him at fifth overall among qualified hitters in 2018. This will, inevitably, drag down his BABIP. Yet, I’d expect something like the .252 BABIP Ramírez produced last season or even a little better given the rest of his batted-ball profile as he’s pulling the ball less now, and BABIP on pulled balls in play is lower than balls hit the other way. An unsustainably high pop-up rate (13.4%) will likely come down as well, supporting BABIP regression.

Plate Discipline

Ramírez also has notoriously excellent plate discipline. This year, his 14% strikeout rate is higher than the consistent 10-11.5% rates he posted the past four seasons. And the increase is supported by a 7.2 SwStr%, up from the 4.2-5.4% rates from 2015-18. But it’s early, and there’s still time for that to normalize. Last year, Ramírez posted a 15.2% walk rate, supported by a 22.3% chase rate. This year, his chase rate is only up a point and a half, so I expect his 8.6% walk rate to crawl up much closer to the 15.2% mark from last year.

Walking at a potentially 13% clip and striking out 14% (or less) of the time is great. It does not scream a .157 batting average to me. Particularly with his batted-ball profile yielding BABIP regression, Ramírez’s batting average should improve. But how much? His xBA is only .225. What if it improved significantly from .157 but only to .225?

Let’s look even further under the hood to see whether he can improve on his .225 xBA and give us, at least, a batting average closer to the mean for fantasy baseball.

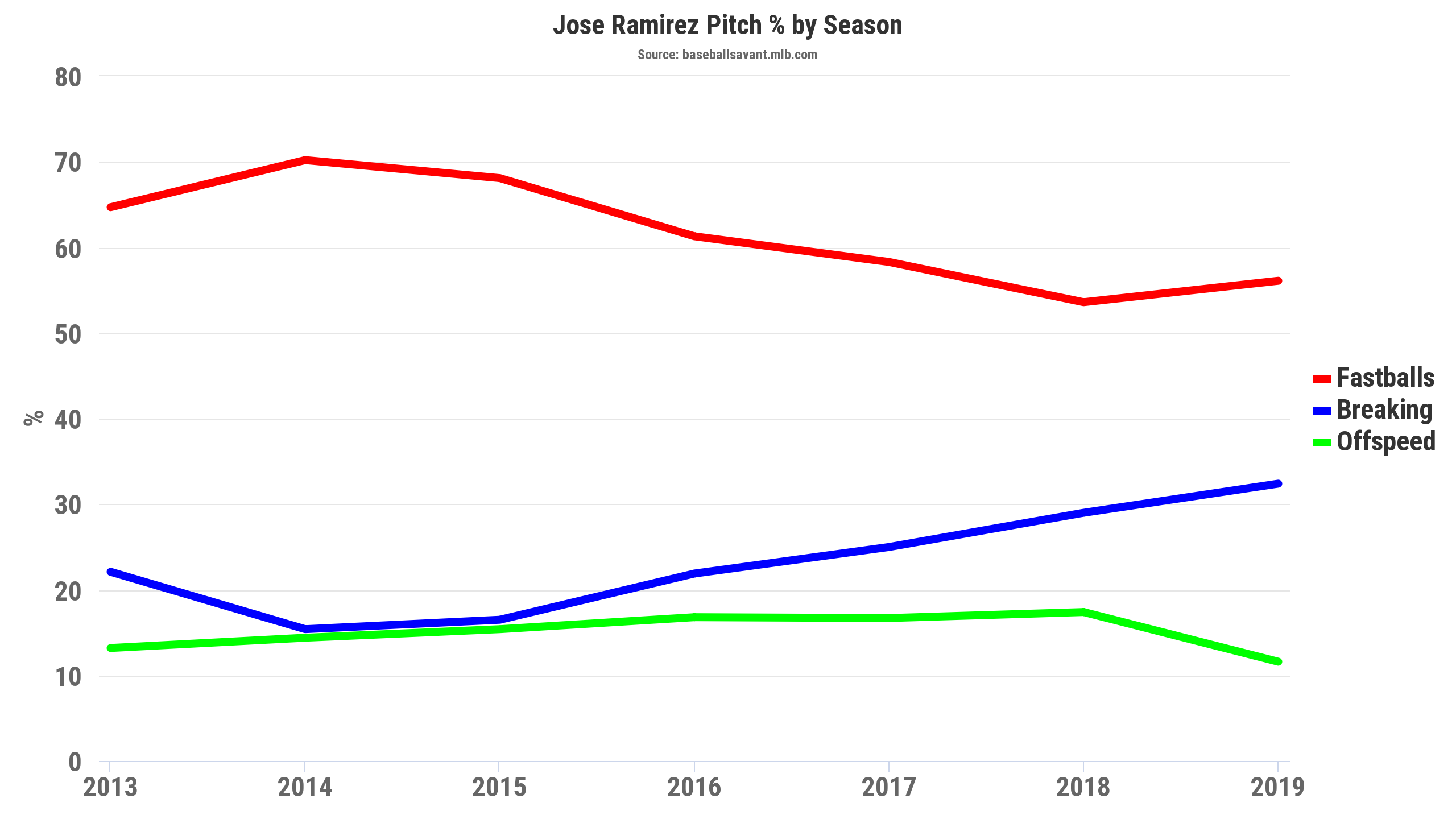

Ramírez has seen 204 fastballs, 123 breaking balls, and 41 offspeed pitches this season. Given that offspeed pitches only represent 11.1% of the pitches he’s seen, I’ll eliminate them from my analysis for simplicity’s sake.

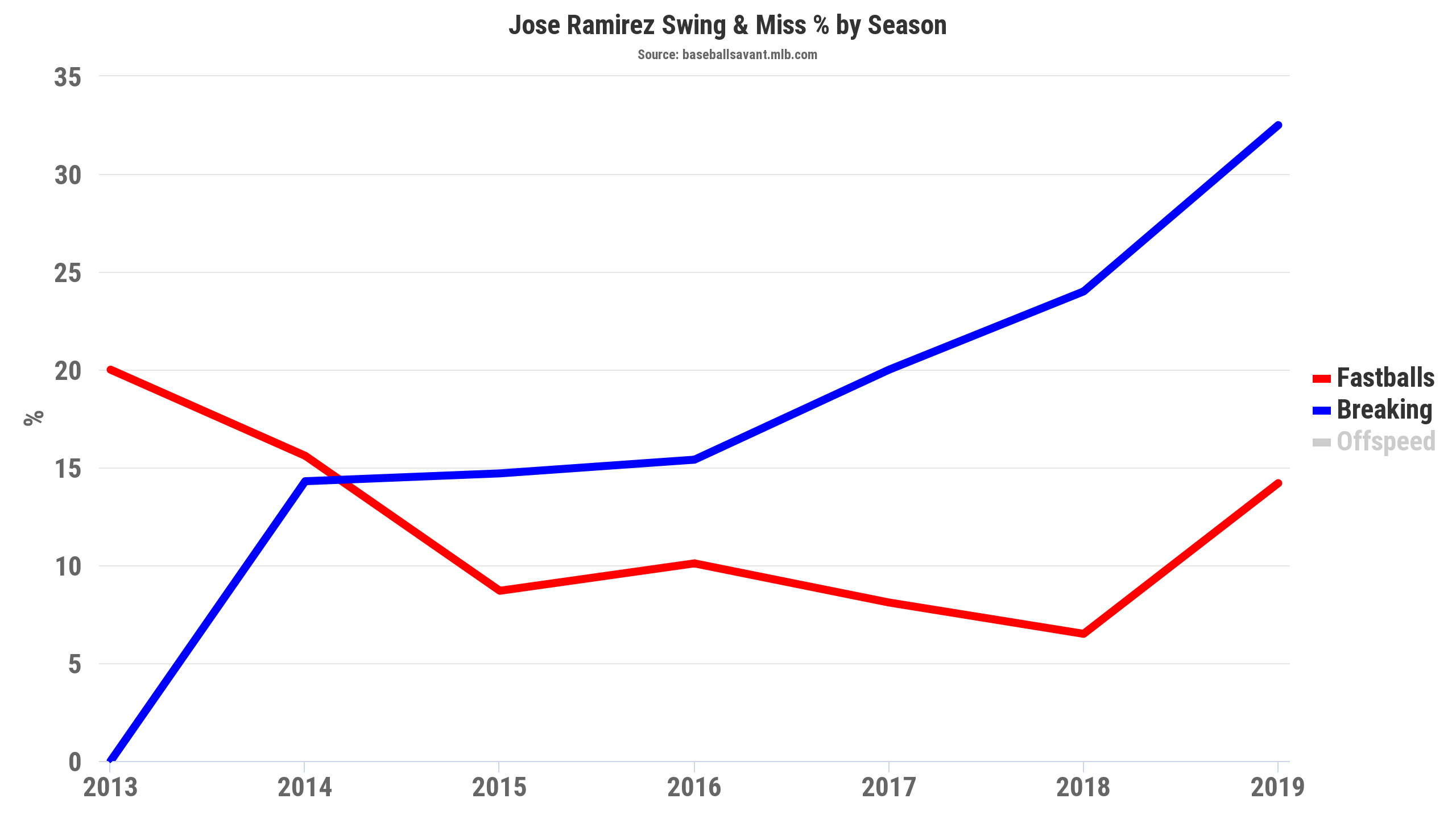

Last year, the line on Ramírez was that he couldn’t hit breaking balls. This year, he’s whiffing more on both breaking balls and fastballs. His average is actually up on breaking balls to .278, and given that league average results on breaking balls is worse than on fastballs, that’s quite good. It’s unsupported by his .156 xBA on breaking balls, however, which is unsurprisingly low given the increase in his whiff rate on them from last season, a year in which his xBA on breaking balls was .213. With a higher whiff rate comes a lower expected batting average, so we can presume he’s actually gotten lucky on breaking balls.

That doesn’t really concern me, though, because Ramírez was excellent last season despite his struggles against breaking pitches by being an elite fastball hitter. Instead, what’s more concerning is Ramírez’s performance on fastballs. Like most hitters, fastballs are the majority of what Ramírez sees (55.4% of all pitches). But as you can see above, his whiff rate on them has more than doubled this season, jumping from 6.5% to 13.7%.

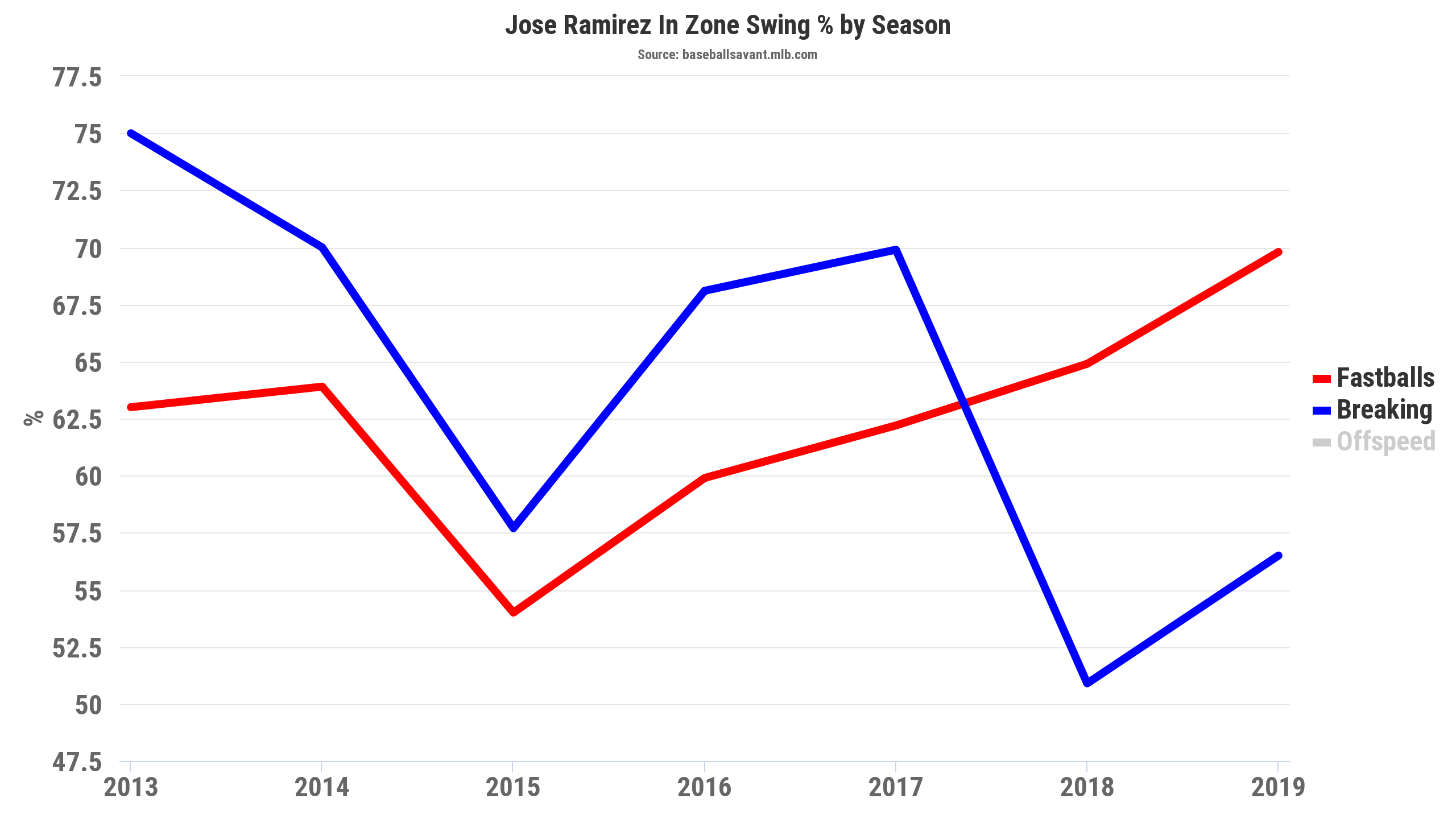

What’s really interesting is that Ramírez is doing four things differently: First, he’s swinging more at fastballs in the zone, which is a good thing. Second, he’s chasing more fastballs out of the zone, which is a bad thing. Third, he’s whiffing more on fastballs in the zone, which is also bad. Fourth, he’s whiffing more at fastballs out of the zone, which is even worse.

These four facts are reflected in Ramírez’s overall increase in Swing% (up to 41.9% from 38.6%) and SwStr% (up to 7.2% from 4.7%). I actually like that Ramírez is more aggressive on fastballs thrown in the zone and that his overall Z-Swing% has increased 4.3 points while he’s maintained a relatively constant chase rate as I noted above (up just 1.5%). This suggests his zone recognition has improved from last season. He’s actually swinging at more pitches in the zone this season, so maybe if he regains his timing from last season, he’ll stop whiffing on them and start turning them into productive balls in play. That’s merely speculative though.

My takeaway is that Ramírez is whiffing more on breaking balls and fastballs, but swinging at more pitches in the zone than last year. He’s only 26 years old, so it’s unlikely his vision has declined to the point where he’d start struggling to catch up to fastballs. No, I imagine Ramírez is just pressing given the lofty expectations placed on him, and the fact that he’s swinging at better pitches is a testament to batting average regression. It’s unclear whether the increase in his swinging strike and whiff rates will continue, but I’m at least glad to see him swinging at better pitches. That, in combination with Ramírez’s unnaturally depressed BABIP, leads me to believe regression is coming.

With all of that said, I think he can at least reach his xBA mark of .225, and I expect better.

Ramírez’s Secret Sauce

Right now, Ramírez’s 3.0 HR/FB% sits far below the 16.9% and 14.1% marks from 2018 and 2017, respectively. Interestingly, his Statcast power metrics are actually better than last year. As I explored in a recent article, all we really care about for determining HR/FB% regression is exit velocity on fly balls and line drives as well as Brls/BBE%. The latter encompasses most of the other Statcast metrics, such as hard-hit rate and average launch angle, to the point where adding them back into the equation adds no predictive value to a hitter’s expected HR/FB%.

With that said, Ramírez’s Brls/BBE% is up to 9% from 8.5% last season, and his exit velocity on fly balls and line drives is up to 93.6 mph from 92.4 mph last season. There isn’t some big problem with Ramírez’s raw power.

In fact, Ramírez’s Brls/BBE% and exit velocity on fly balls and line drives, both this year and last year, are decidedly average. Last year, he ranked 164th in exit velocity on fly balls and line drives and 116th in Brls/BBE%. How, then, did Ramírez achieve a 16.9 HR/FB% and hit 39 home runs, and why did we ever expect it to continue?

Ramírez actually made his hay by outperforming his Statcast power metrics. Statcast metrics fail to account for directionality. Put differently, a hitter who pulls his balls in play is more likely to hit home runs than a hitter who sprays to all fields. For instance, as Nick Gerli notes, from 2016-18, a righty’s pulled fly ball down the left field line produced, on average, a 1.786 slugging percentage, whereas fly balls to the center-left portion of the field resulted in a .757 slugging percentage. Not all 93.6 mph fly balls are made equal.

The reason is fairly obvious. Other than it being easier to generate power to the pull side, fences are deeper in the middle of the park than down the line. You don’t have to hit the ball as far when you pull it for a home run.

Despite otherwise average raw power metrics, Ramírez had a 50.0 Pull% and 45.9 FB% in 2018. Try filtering the Fangraphs splits leaderboards page for pulled fly balls, and then sorting the page by total pulled fly balls. Here’s what you’ll find:

| Name | 2018 Pulled Fly Balls | MLB Rank |

| Jose Ramirez | 82 | 1st |

| Mike Moustakas | 77 | 2nd |

| Alex Bregman | 74 | 3rd |

| Miguel Andujar | 69 | 4th |

| Rhys Hoskins | 68 | 5th |

Ramírez sits above all of MLB with 82 pulled fly balls. Those balls in play were accompanied by a 916 wRC+ (yes, that’s accurate) and a 78.8 Hard%. Given how hard he hit those pulled fly balls, it’s no surprise that 30 of his 39 home runs came on pulled fly balls. Good for a 76% home run rate!

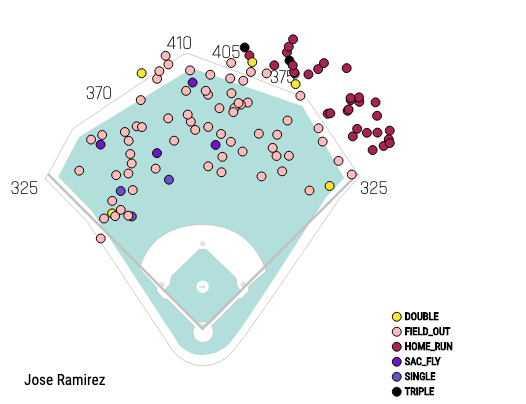

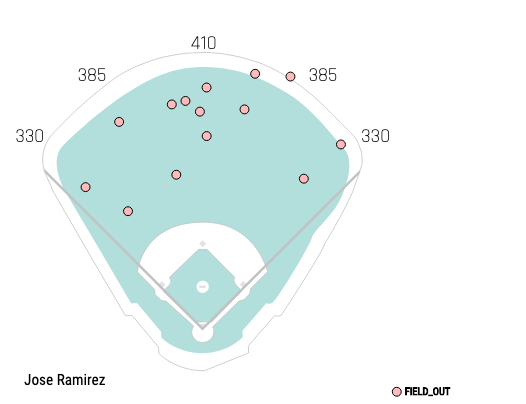

I’m going to use Ramírez’s lefty spray charts to show his pull tendencies. He’s a switch-hitter, but I selected only his lefty spray charts because it’s more difficult to tell what’s occurring by looking at the pitches he’s seen from both sides, as the pitches he hit as a righty make it look like he sprays to all fields. Moreover, he bats lefty in over 2/3 of his plate appearances given that the majority of MLB pitchers are righties, so that’s the better sample to choose.

You can probably guess where I’m going at this point. Those are all of Ramirez’s lefty fly balls from last year. Here’s this year:

This year, Ramírez has just four pulled fly balls. For context, the league leader in pulled fly balls, Eddie Rosario, has 16 already. This is further reflected in the fact that his pull rate is down to 29.6% this year, a far cry from the 50% mark of old.

| Name | 2019 Pull% | 2018 Pull% | Difference |

| José Ramírez | 29.6% | 50% | -20.4% |

| Alex Bregman | 31.8% | 48.4% | -16.6% |

| Justin Smoak | 34% | 49.2% | -15.2% |

| Carlos Santana | 33.3% | 48% | -14.7% |

| Marwin Gonzalez | 30.4% | 44.1% | -13.7% |

In fact, of qualified hitters, Ramírez had the largest drop in Pull% from 2018 to 2019.

Notably, Ramírez has gotten a little unlucky on the four fly balls he has pulled. Despite hitting three of them “hard” according to Fangraphs, he only has one home run to show for it. Last year, he had a 76% home run rate on pulled fly balls, much better than the 25% rate this season. Hence, his xSLG is actually .408 this year, much higher than his actual .229 slugging percentage.

Imagine for a moment that Ramírez maintains this pace of pulling fly balls. So far, he has four in 93 plate appearances. Even generously assuming he reaches 698 plate appearances like last season, that equates to 30.02 pulled fly balls. Again, I’ll generously assume he maintains the 76% home run rate on pulled fly balls from last year. At that rate, he would hit 22.8 home runs on pulled fly balls this season. However, he’s already underperformed a bit by missing out on two of those pulled fly balls, leaving him with 21. If he hits another nine homers from non-pulled fly balls as he did last season, that would put him at 30.

I think Ramírez owners would take 30 homers. Given he’s gotten unlucky to this point on pulled fly balls, it’s possible he gets there. But that projection assumes he gets another lofty complement of plate appearances, maintains last year’s excellent home run per pulled fly ball ratio (which he isn’t right now), and hits nine non-pulled fly ball homers (he has none so far, despite hitting more fly balls to center and the opposite field this season). Perhaps 20 to 25 homers is more reasonable.

With middling power peripherals, Ramírez needs those pulled fly balls to regain his elite power form. That’s how he generates his power. That begs the question: why isn’t he pulling the ball anymore?

The Book is Out on Ramírez

When I first decided to look into Ramírez, of course the deflated Pull% stood out to me, so I wanted to see if he was doing anything differently, like closing his stance, which might yield more hits to the opposite field.

I stared at some images of Ramírez for quite awhile and, for the life of me, I couldn’t spot a difference. He’s still standing open, near the plate, with his hands high and weight on his back leg. Same small leg kick as last year. Honestly, I expected a closed stance, allowing him to reach outside pitches and swat the ball to the opposite field, while simultaneously making it more difficult to pull the ball. Closing one’s stance makes you late to the ball, whereas you have to get out in front to pull the ball. But nothing is perceptively different about his stance.

You may have heard that Ramírez’s prolonged slump dates back to the end of last season. That much is reflected in his pull rates, as, since September 1, his pull rate has been 36.2%. Whereas up till that point last season his pull rate was a whopping 51.4%. What changed in September?

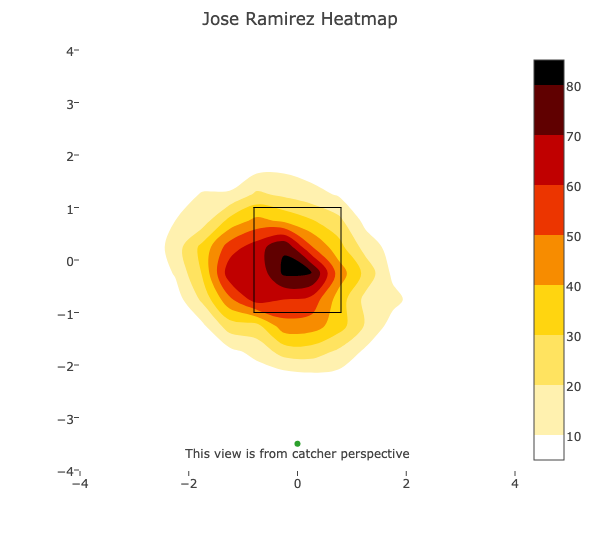

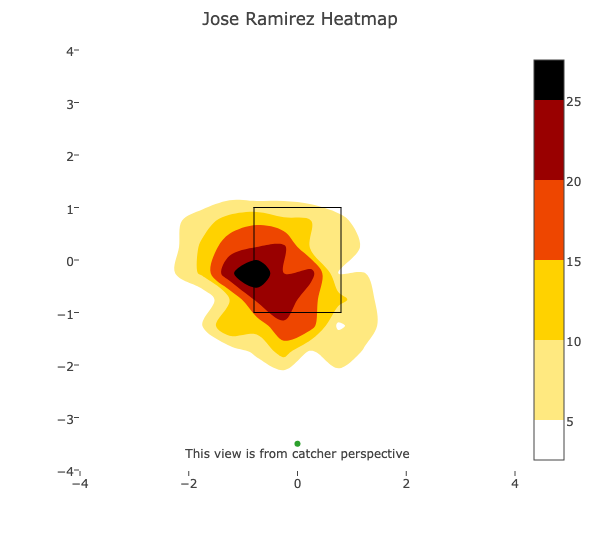

This is Ramírez’s lefty heatmap for all 2018 games before September 1. Pitchers couldn’t figure out how to pitch him. That’s why the heatmap is a dark cluster in the middle of the zone. Those are some good pitches to turn on and pull for fly balls, which is exactly what Ramírez did up to that point.

Yet, since Sept. 1, pitchers have much more deliberately pitched Ramírez low and away. Now, he’s seeing more pitches away as the heatmap clusters off the plate rather than in the heart of it. There’s even more red off the plate entirely, as well as below it. Pitching this way stifles his ability to turn on a ball and pull it.

Just think about it. Pitches on the inner half of the plate are much easier to pull because there’s a shorter path to the baseball. So long as you’re early and can get out in front of the ball, you’re almost guaranteed to hit it to the pull side. Even pitches that are in the middle of the zone can be pulled.

However, when everything is going away it’s much harder to turn on the ball. It’s extremely difficult to pull an outside pitch because you’re doing so late with the end of the bat, instead of the middle of the barrel. It’s just difficult to get your bat around a ball that is farther away from you. Some hitters can do it, but Ramirez simply doesn’t have the raw power to pull an outside pitch for a home run.

As a result, I’m not sure what the fix is for Ramírez’s power drought. He’s already “going with the pitch” by taking outside pitches to center and the opposite field. He also currently stands very close to the plate, so he can’t simply adjust his stance to get closer to the ball and pull outside pitches for power. In addition, I don’t think he has the strength to pull outside pitches for home runs. But his limitations, as evidenced by Statcast’s power metrics, suggest he needs to pull fly balls in order to hit for elite power. If he continues getting pitched away, he’ll only have mistake pitches to hit for home runs.

Conclusion

Regression is coming for Ramírez. Owners should hold tight and cross their fingers that the BABIP gods will look more favorably upon him, as I believe they will. He still has excellent plate discipline, and he’s actually hitting the ball harder than last year. He’s not broken.

Unfortunately, the book is out on Ramírez, and pitchers have adjusted to his pull-heavy tendencies by pitching him outside. As of now, he has yet to adjust back and without doing so, he cannot be the elite power hitter he was in 2018 given his extreme dependence on pulled fly balls. I hold out hope that he can, but am not sure what the easy fix would be.

Perhaps he reverts to the Ramírez of old. This is sort of my expectation. Ramírez’s spray charts in 2015-16 showed a guy who hit to all fields, as he is now, with .300-plus batting averages and mediocre power. Indeed, I already expect his batting average will improve. Maybe he continues punishing mistake pitches over the heart of the plate, which gives him a little more power than he used to have, particularly given his increased exit velocity and the fact that he’s still hitting significantly more fly balls than he did back then.

As he continues to hit more to center and the opposite field, however, his BABIP will increase and his power will remain depressed, and he will slowly revert to the 2015-16 Ramírez, a guy who also maintained much lower pull rates. In this way, he could help more in the batting average department while maintaining good, though not elite, power production. That 20 to 25 home run projection comes to mind. And with 30-plus stolen bases, he’s still an extremely valuable fantasy asset.

Ramírez probably won’t punish 39 baseballs this season, but he’s (d)evolving, and so should your expectations.

Photo by Frank Jansky/Icon Sportswire

Great write up! I’ve got Kris Bryant who is also struggling. Do you think I should offer a swap for Ramirez?

Yes, even in spite of my reservations, I would make that swap in a heartbeat. Ramirez will swipe 20 more bags than Bryant. At the end of the day, he might still hit more homers given how lackluster Bryant’s been for awhile now.

I wouldn’t dare offer Goldy for Ramirez…would I?

If you need steals, then sure. If not then don’t

I recently traded Harper and Marco Gonzales For Matt Chapman and Ramirez, i feel pretty good about this one. h2h points league

While I’m clearly concerned about Ramirez’s power, i still think you won that trade.

Terrific article, Dan!

It’s interesting how Ramirez slowly hacked his way into becoming a good home run hitter by incrementally increasing his pulled FB rate. But pitchers adjusted.

But as you said, his floor is still great.

Thanks Nick! Much appreciated