Leaguewide adjustments in Major League Baseball don’t occur very often, so when the infield shift became popularized during the 2012 season, it revolutionized key parts of the game. With its implementation increasing every year since, the shift has led to a number of unexpected outcomes—most critically, the transformation of lefty sluggers’ approaches.

Moreso than righties, left-handed hitters have been forced to alter their approaches at the plate to combat the shifted defense. One of the greatest switch-hitters in MLB history, Mark Teixeira, who hit 297 of his 409 career home runs from the left side, doesn’t consider this fair. “I think lefty hitters today are just as talented as righties, but are at a serious disadvantage because the shift discriminates against one set of players, left-handed hitters, and them only,” Teixeira wrote in an email.

Here is a specific example of lefty sluggers’ hardship. In this at-bat, Chris Davis, the second-most shifted player since 2016, hits a 100 mph ground ball between first and second base with two outs in the bottom of the ninth. Ten years ago, the grounder may have been a base hit to keep the contest alive, but in 2018, it was one of the easiest outs to end a baseball game.

Here is a juxtaposed example of a righty slugger hitting a ball into the shift. In this case, Rhys Hoskins, the most shifted against righty, hits a 98 mph ground ball between shortstop and third base at almost the exact inverse angle of Davis’ groundout. However, in this situation, not even seven-time Gold Glove winner Nolan Arenado can make this diving play as it rolls into the outfield. Everything about these two plays are almost identical; however, the major distinction is how the two shifts are configured. Below are two conventional examples of the shift for each type of hitter.

Not only does Teixeira’s claim of a “serious disadvantage” pass the eye test, it is also indisputably justified by the statistics. In 2018, of the 60-most shifted players, 58 of them were left-handed batters, and in this past season, that number remained steady with 56 out of the top 60 batting from the left side. That is in spite of only 35% of the league’s population batting left-handed. Overall, lefties are shifted against 193% more of the time than righties. The huge disparity between lefties’ and righties’ shift percentages is a result of the infield configuration discrepancy between the two. It’s a much easier play to throw a lefty out at first base from shallow right on a pulled ground ball than it is to retire a righty from short left field. This disadvantage for lefty hitters is rooted in the great disparity in throw length. The numbers back that up: On pulled ground balls with a shift over the last five seasons, righties retained a batting average that was 65 points higher than that of lefties. As teams across the league are shifting more frequently, all hitters—especially lefties—have been forced to adapt to this impediment.

When St. Louis Cardinals lefty slugger Matt Carpenter entered the league in 2012, he had a distinct approach, and it was not one of a power hitter. In 2013, he led MLB in base hits and hit only 11 homers. After a down year in 2014, he realized an adjustment was necessary. “Teams knew where I was hitting the ball, so my average went down,” Carpenter said. “They pitched me a little tougher, and my slugging went down. My approach of just laying balls to the opposite side wasn’t working.” In 2015 and ‘16, he adapted his swing to hit it over the shifted infielders. “The best solution to beating the shift is hitting the ball in the air, so I started learning how to drive the ball. I started pulling the ball a bit more, and over the years I just morphed into what I am now.” This modification paid off big time. During the 2018 season, Carpenter finished third in the National League with 36 home runs and finished ninth in the NL MVP voting. This past year, injuries hindered his power numbers.

In MLB’s current state, three distinct breeds of lefty sluggers have successfully executed an approach to beat the shift. Carpenter fits in with the first strategy, which involves driving and pulling the ball with low ground-ball rates. Texas Rangers outfielder Joey Gallo is another player who utilizes this tactic and is the absolute embodiment of this trend. Last May, Gallo achieved a feat that had never been done before: He smacked his 100th career dinger before notching his 100th single. Although this seems like a fairly straightforward, yet exciting, achievement, it actually indicated a noteworthy change that had taken place among the lefty slugger population: the adoption of the fly-ball trend. With the infield shift damaging lefties’ batting averages (pre-shift pulled ground-ball numbers were nearing .190 and are now approximately .110), Gallo was one of the many players who realized the best way to beat the shift was to slug it over the adjusted defense into the gaps or the stands. Since 2016, Gallo is second in the league in average launch angle, and unsurprisingly, the third-most shifted-against active player.

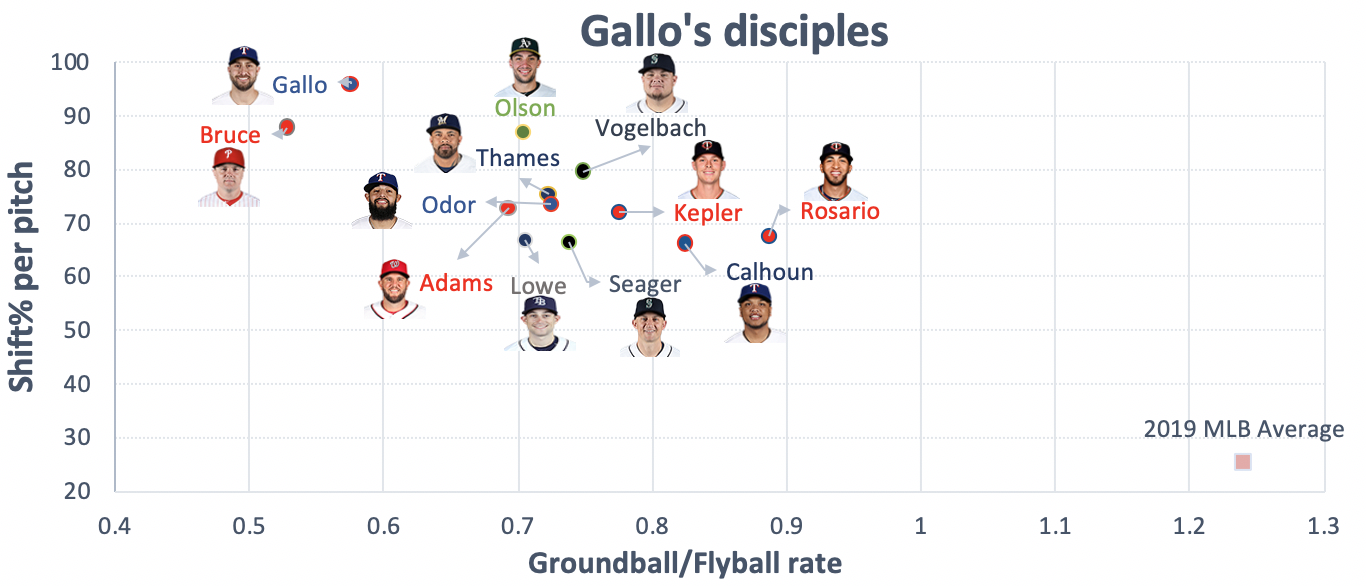

Gallo was one of the trailblazers, though he isn’t the only lefty slugger who has embraced this strategy of launching the ball. All of the batters shown on the graph below are shifted against a significant amount of the time but own such a low ground-ball-to-fly-ball rate that they still bring an abundance of offensive value to their team. In this past season, each of these 12 batters had an ISO over .210, a measure of a hitter’s raw power (average is .180), confirming they are true sluggers.

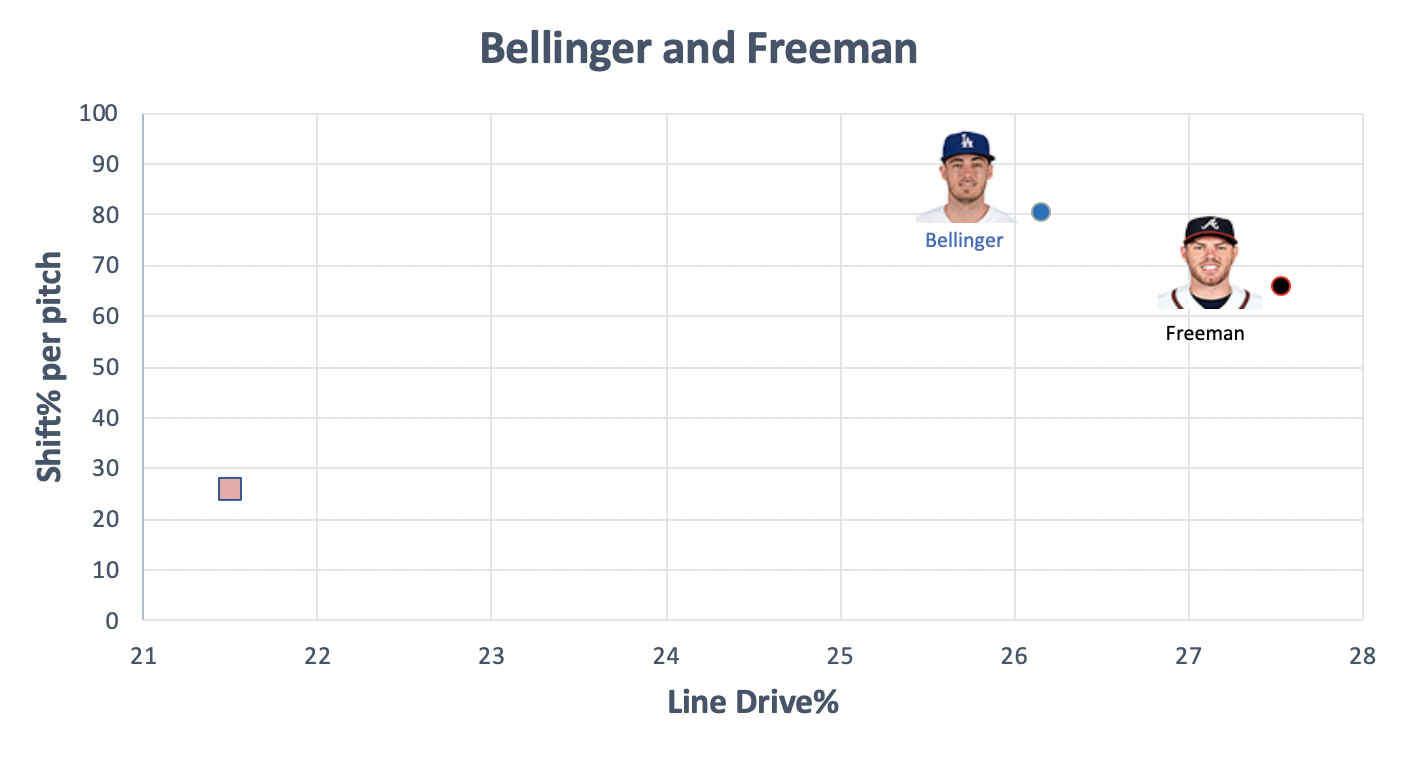

The second breed of lefty slugger contains only two players—Atlanta Braves first baseman Freddie Freeman, and Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder Cody Bellinger—who are among the best in MLB. Managing to pull the ball a significant amount of the time, these two All-Star lefties have overcome the shift by belting an outrageous amount of line drives and hard-hit balls. In 2019, with a shifted defense, no player hit more line drives than Bellinger and Freeman. The former hit 104 liners with a batting average of .596, while the latter slugged 99 of them with an average of .556. So clearly, retaining high shifting percentages has not negatively impacted them.

These two types of sluggers have put an increasing emphasis on hitting the ball into the air, which has led to lefties’ runs created (wRC)—a stat that tracks a hitter’s standardized ability to create runs—reaching its highest point since the 2009 season. This is occurring even with the shift climbing to an all-time high against them, confirming how fly balls and line drives are the key to defeating it. Overall, shifts rose from 29.6% to 41.9% from 2018 to 2019.

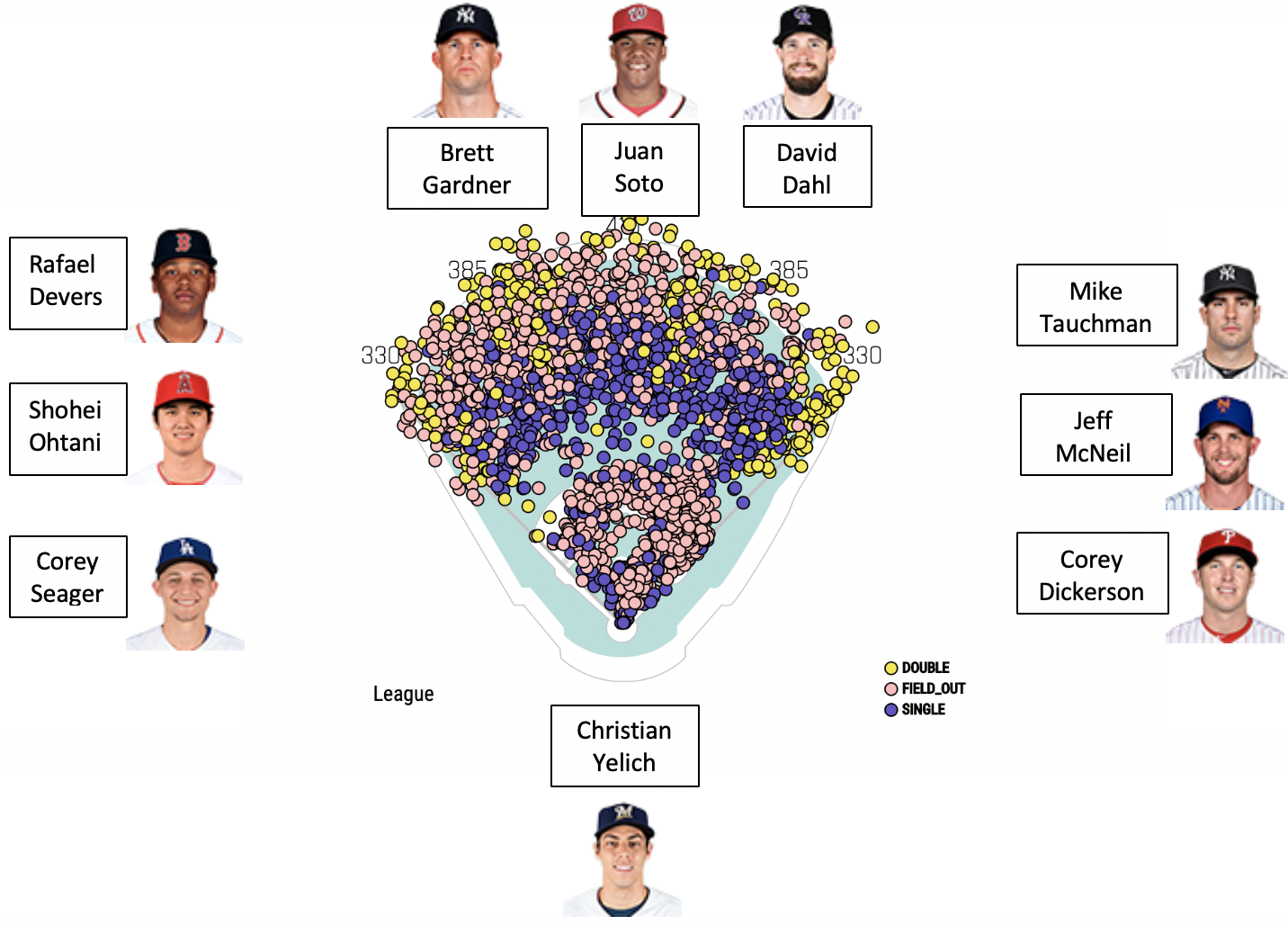

The third and final class of lefty slugger who’s beating the shift is exemplified through none other than Christian Yelich. We’ll call this group the “un-shiftables.” Only special players retain the ability to drive the ball line to line on the ground or in the air. According to Frank Marcos, the former Senior Director of MLB Scouting Bureau, these are the model lefty sluggers: “Ideally, teams would love to have LHHs who hit for power to all fields, thus reducing the effectiveness of the shift,” said Marcos in an email.

By definition, these lefties are difficult to shift against because their batted-ball patterns are so unpredictable, curtailing the shift’s imbalances completely. The extraordinary part about these hitters is how they can still maintain their power. This past season, there were 10 lefty sluggers with an ISO over .210 and a shift percentage below 30% or a pull percentage below 40%. The data displaying their batted balls has so much deviation, it’s challenging to discern which side of the plate they are batting from.

The un-shiftables

Although the three distinct types of lefty sluggers in today’s game—the pull-frequent lefties with extremely low ground-ball rates, the guys who rip ridiculous amounts of line drives through the shift, and the special sluggers who can spread the ball around the entire field—have learned to handle the shift’s complications, there is one more type with a less distinctive and more ineffective style. Players such as Kole Calhoun, Mitch Moreland, Anthony Rizzo, and Bryce Harper are all somewhat successful lefty sluggers, utilizing different elements of each of the three reigning groups.

This original, divergent route has been successful because of the level of power produced by each of them, but these lefties could still bring more value to their team if they stuck with one of the three specific types of approaches to curb the shift more successfully. This past season, these four lefties performed rather poorly against this adjustment in infield positioning. All four of them had at least 40 pulled ground balls against the shift. In total, they retained a .093 average (total of 20 for 215) in these instances. Especially with the shift’s usage pointing toward escalation, they might want to consider merging with one of the other breeds to help thwart the shift’s impact. Tweaking your swing is never an easy task, but based on the amount of pulled ground balls that Calhoun, Moreland, Harper, and Rizzo hit into the shift, it seems like a necessary adjustment to prevent them from becoming potential victims of the evolving game. If they can decrease their ground-ball-to-fly-ball rates to similar standards of what Gallo’s disciples accrue, then that may be the safest tactic to ensure stability.

To be successful as a lefty slugger nowadays, each player must utilize a certain approach to limit the shift’s inequities. If not, they could join the long casualty list of one-dimensional lefties who only hit homers. “You rarely see the big, bruising, left-handed slugger, like Adam Dunn, anymore,” Carpenter said. “Those guys used to be everywhere, and they just don’t exist anymore.” These three new types of hitting strategies helped evolve the lefty slugger from the Dunn-esque hitter who would’ve had a gloomy future with the shift, into the diverse and distinguished sluggers in today’s game.

Until recently, the infield shift generated a legitimate problem for lefties, and these various solutions are all relatively newborn. It’s hard to say what the future holds for lefties and the shift. But what is certain is that lefties will always have to tolerate a greater burden than righties. Sure, defenses will continue to shift against righties, but not as often as they will against their lefty counterparts. Lefty sluggers remain constrained to certain approaches. Besides a rule limiting defensive alignments—a controversial topic for another article—there is no quick fix the league can make to buck or reverse the shift’s impact. It’s up to the players to adapt with the changing game around them.

Featured Image by Justin Paradis (@freshmeatcomm on Twitter)

The effects of the shift are always greatly overstated. Sure it takes a way a few singles but it gives away more. That Chris Davis swing is a great example – that was a rollover could-have-been single in a three run game with two outs in the ninth. It wasn’t a good swing nor would it have mattered for anything. In addition, there is no such thing as a typical shift. The same thing as what you are calling a typical shift can be accomplished without an overshift…. which would make it a traditional defensive alignment. The value to standing on the grass is probably negative as it takes away more than it gives – specifically it takes away a few LD a year, but I am sure it is offset by infield hits because infielders never charge from back there and they get eaten up by the lip a lot. My point is that all we have to do is not waste that third player who rarely makes the play on the wrong side of the field and this conversation doesn’t exist. If we just stuffed the 2B way over in the hole, then we aren’t talking about shifts at all – it would just be a standard alignment vs a player who is dead pull… probably more aggressive than past generations but all we are ever talking about is that 2B shifted way over… which in itself isn’t an overshift. I don’t think beating the shift is terribly hard for a hitter with something resembling an approach. More left handed hitters lack an approach. Freddie Freeman is an excellent example of a player that should not be shifted against in the first place as he isn’t dead pull… which to me kind of tells you how scientific this is. I very much question the “analysis” and “planning” that goes into shift deployment. Its certainly not rocket science – just stuff a 2B 3 steps over from where he would play a normal left handed hitter. I am certain that the optimal alignment is that with the SS playing right up the middle – watch baseball through that lens, its pretty hard to dispute that would be the most profitable alignment.

Being dead pull has never been a successful strategy and is always the mark of a hitter that could be better. Yes, I do wonder how much better David Ortiz could have been. I imagine an alternative train of thought would be something along the lines that these lefty hitters are worse hitters which is why they can’t beat a shift. Being left-handed is an advantage for a pitcher due to handedness – in other words in a stuff/command contest rightist would win because that is kind of necessary to succeed, whereas simply having one good pitch can get a lefty a job. Many an untalented LHP has gotten a college scholarship on handedness alone. Left-handed pitchers certainly succeed with less pitchability solely due to their handedness and I am certain the same is true of hitters. You can blame the defense or the hitters or even both. It would make sense (to me at least) that someone like Tex who peaked in college would be full of excuses. He does seem to enjoy a microphone in front of his face.

Here is my take on the three categories.

1) Hit more HR group. This is just going to be volatile as this is the most volatile of all approaches. The difference between a lazy FB and a HR is not much in most cases. I don’t think it is a plan as much as an observation after a successful run. It is one of those after the fact plans. I would speculate that it often is what happens right before complete irrelevance. Anyone can hit more FB but going back to more LD doesn’t really happen much.

2) Hit LD group – LD are the mark of a good hitter. These guys will succeed and it doesn’t matter what anyone does. Unfortunately you can’t make this adjustment – its what everyone would like to do.

3) Hitters who use the whole field. Again, this is the other mark of a good hitter. Obviously this makes quick work of a shift. I imagine lefties are less liekly to do this as they can have so much success on a simple handedness advantage.

Good hitters hit LD and they use the whole field. Lefties are just less likely to be those things if for no reason other than raw number of players. I think the fact that they beat up on RHP only lets them get away with a more flawed approach. I would imagine that right v left handed hitters distribute balls differently – lefties are more likely to do a straight roll over ala Crush Davis above and I bet righties spray it around the left side more. Its a bit of apples and oranges at least. Personally, I don’t see any evolution of left handed sluggers – they seem a lot like they have always been to me. I don’t buy that they are making adjustments or that they can become one of the three successful categories by looking at a heat map or trying to be those things. In paragraph one you are outing how the shift is winning and in the last paragraph you are saying the players are winning. That sounds about right to me as I don’t think there is really much here to draw conclusions from. I think the idea that you don’t see Adam Dunn is just kind of absurd. You never did see many Adam Dunns. You have plenty of Joey Gallos which are similarly giant sluggers geared to do one thing. You sure as Heck have Kyle Schwarber and Dan Vogelbach who I would say fit that mold… I would also argue that being a dead pull hitter is not a new problem. Rolling over ground balls has never been a good bet. Its possible that the shift only works because hitters have gotten worse at hitting. I am sure they eat better and do more stuff off the field, but I am also sure that they face live pitching less – getting beat by pitchers looks like pulled GB and Ks… which are markers in today’s game. A focus on hitting balls for max EV would lead to more pulled GB as it is certainly an approach that is highly exploitable by decent pitching execution. I believe that more flawed hitters have jobs now that ever before as it plays well with juiced baseballs. i think a lot of those quality hitters that could torch a shift don’t get opportunities at their expense. Think about how marginalize AVG has become.. which is a decent proxy for groups 2 and 3.

Wow, I really appreciate your analysis! However, I think you understated the impact of the shift on lefties. Playing on the grass absolutely takes away more outs than it gives. According to the data, only 2.2% of the at bats when lefties are shifted against end up as an infield hit. Rather, 18.5% of lefty at-bats with a shift end up as a groundout. Clearly based on this major juxtaposition in percentages, the shift leads to a signficant decrease in the amount of singles for lefties, and are not aided by infield hits, which happen very infrequently.

Also, another take of yours claiming dead-pull hitters can’t be successful is hard to agree with. The 12 players in my high launch-angle/FB group have an average 111.3 wRC+. This is an above-average weighted runs created total, and shows how each of these players have been successful with high-shift %’s/ high-pull rates. I’m sorry, but I’m having a little trouble agreeing that “Teixeira peaked in college”, based on the fact he is 5th all-time in HR’s from switch hitters, and truly had an illustrious career after college…

I definitely agree with some of your other claims. Especially how the best lefty hitters are the ones that hit-liners and can spread the ball around the field, but that still doesn’t diminish the value that pull-heavy lefties can have. I’d love to any answer any more of your questions.

Best,

Simon

Love the article. Very insightful. I think MLB should institute a ban against the lefty shift. No infielders should be allowed to play on the outfield grass. This would even the playing field for lefties.

Hey Joel,

I really appreciate the comments. And I agree with you, I think it would be very interesting if MLB banned the shift to help curb the positioning in the outfield. Feel free to send me any more thoughts or questions.

Best,

Simon