In the early going this season, four out of the top five players by WAR have fathers who played in the major or minor leagues. Of course, Vladimir Guerroro Jr’s dad played in 16 MLB seasons. Mike Trout, Kris Bryant and Ronald Acuña Jr. had fathers who played in the minors. Out of that top five, only JT Realmuto did not have a father that played professionally, although he did play in college.

Beyond the current WAR leaderboard, Major League Baseball is flush with stars who come from families with MLB experience. Fernando Tatís Jr. Cody Bellinger. All of the Blue Jays.

Should we care?

The large adult sons of major leaguers are unquestionably among the brightest and most exciting young stars of the game and clearly weren’t drafted or given opportunities based on their names. Heck, Mike Trout wasn’t even drafted based on his outstanding performance, or he would have gone much higher. The prevalence of Major League legacies, however, might be thought of as symptomatic of a potentially larger issue. And while the result is fine (some might even say ideal), there are reasons for concern if, in fact, the children of Major League players are more prevalent in the league.

Imagine a continuum of the pool of Major Leaguers, where on one end, the rate of professional baseball players whose fathers also played professionally is the same as that of the general population. On the other end of the continuum, only sons of former professional players are in the possible talent pool. In the latter scenario, the talent level or play on the field might not be troubling itself, but it would present a problem where successive generations will have fewer and fewer talents from which to draft or sign. In other words, a restricted talent pool is bad for baseball.

Of course, the true talent pool is somewhere between those two extremes of the continuum. In fact, one would expect players with familial ties to professional baseball to be over-represented in its ranks, both culturally (exposure to baseball from an early age) and physically (athletic traits genetically passed down). A more pressing concern for the long-term health of the game would be if we saw over-representation from sons of Major Leaguers because of issues of access.

Major League Baseball players enjoy robust salaries, with a league minimum of $570,500 per year. It’s safe to say that the families of players (at least, during their playing days) are more well-off than the majority. As a result, they have access to better nutrition, training, equipment, and travel for tournaments and showcases than most.

In a much narrower sense globally, the bigger problem for MLB’s long-term financial health may be that the prevalence of Major League dynasties represents a shrinking pool from a lack of interest in the game. (As an aside, I’ll also take an idle guess that MLB families are not likely blacked out of watching dad’s games at home when they’re not at the ballpark.) With families making up a disproportionate rate of the player pool for MLB, could it signal that other, “regular” families are choosing other sports over baseball?

We can all agree that baseball is unquestionably better for having Mike Trout and Fernando Tatís, Jr. MLB, however, should question whether an over-representation of players born into professional baseball families is symptomatic of larger issues of access or interest to the game.

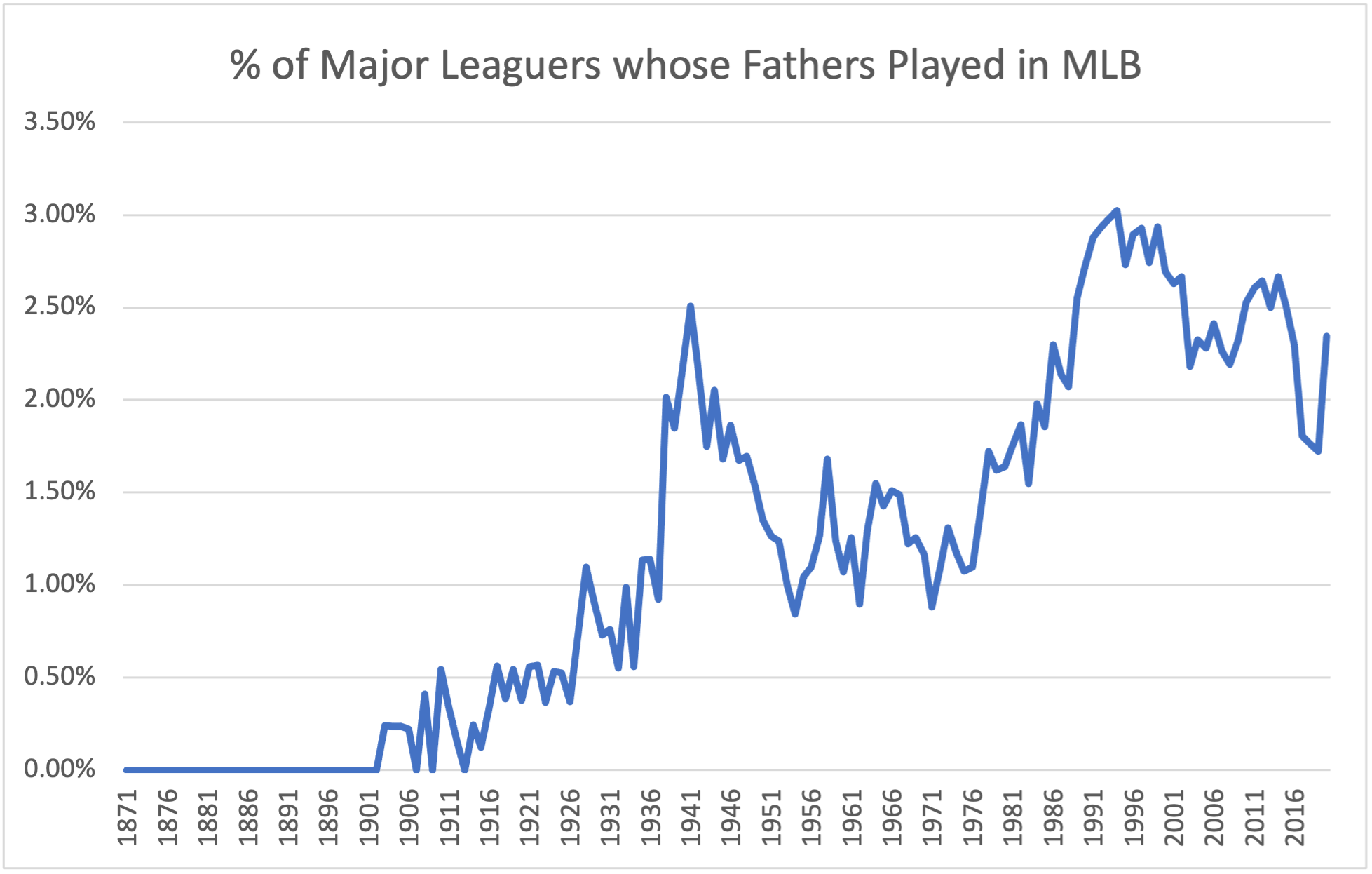

So is this a new phenomenon for concern, or have players always come from MLB families?

The rate of players whose fathers played in MLB as a share of total players has seemed to be on the increase overall since MLB’s inception. It’s not at its highest point ever, but the general trendline is increasing and shows a recent spike.

How have those players performed as a group? To answer that, we looked at each year’s total share of WAR accumulated by players whose fathers also appeared in Major League Baseball:

Overall, major leaguers whose fathers also played in MLB have performed slightly above their expected total share of WAR, averaging .15% more WAR than their prevalence and that share has been on the rise for the past three seasons after a dip 2013-2017.

A lot of that weight seems to be carried by a mid-90s to early-2000s peak. In fact, 1994-2003 produced the ten highest shares of WAR by sons of MLB players in history? Why?

Oh.

https://gfycat.com/flakyonlydrever

Right.

http://gfycat.com/complexfrequenthydatidtapeworm

That the highest-WAR seasons by MLB sons came in a recent peak heyday, and the current crop of young stars like Trout and Guerrero suggests that baseball’s legacies are an asset to the game. Arguably, the best and most marketable players in growing the game for MLB over the past 30 years, if not in its history, have been sons of former players.

The passing of the game on to one’s children has been a staple of baseball’s history, perhaps more than any other sport. The connection from Ken Griffey to Ken Griffey, Jr evokes an heirloom that fathers and mothers pass to their sons and daughters, and perhaps allows us to connect with baseball players in that way.

The growing share of baseball stars and their overall prevalence in the majors whose fathers were also in the league can be a tremendous asset but is not without risks. It is also an indication that MLB should do more to remove obstacles to playing, and enjoying, the game.

Regional blackouts, the lack of marketing around young stars of the game, the costs of playing, and structural societal barriers that restrict access and opportunity are not caused by familial MLB dynasties. But if owners are not careful, those dynasties could end up reflecting the symptomatic and underlying issues that shrink the pool of talent as well as broader interest globally.

Photos from Wikimedia Commons & Icon Sportswire | Feature Image by Justin Redler (@reldernitsuj on Twitter)

Mike Trout’s father played in the big leagues? (He didn’t.)

Woof, drafted never made MLB. Thanks for the catch, fixing.

The topic was definitely worth a look and ties into a lot of the things I’ve seen as issues plaguing MLB’s popularity at all levels.

I think this is more a symptom rather than the disease as you’ve mentioned… It isn’t accessible to many, as the talent pools that are tapped are developed out of (expensive) travel ball and the bridge between getting drafted and the majors is usually a long and difficult one, whereas kids that get drafted in the NBA and NFL are often in the “bigs” within a year or two at most and start getting their cheddar quickly.

Yeah, the development time at MLB is definitely another factor. Not sure if it’d make a huge difference, but ending service time manipulation might tip some athletes’ scales toward baseball.

Adding MiLB to the player’s union or them being able to unionize themselves would be a huge step in the right direction.

Having to work extra jobs because they aren’t even being paid minimum wage is a huge stumbling block to hugely talented athletes that aren’t getting large signing or draft bonuses. If I could play any other sport and get drafted, even if it were a larger concussion risk, I’d take it… unless I were a high-draft target or legacy like those mentioned here.