Great baseball players, and pitchers especially, are often like Pokémon. Getting better breeds evolution; in order to survive, whether as elite or just as a major leaguer, one must always be changing, adapting, finding new strengths, eliminating old weaknesses.

Clayton Kershaw is good at adapting. It’s why he’s still good at pitching. He became the first NL pitcher to reach ten starts last Wednesday, and it was vintage second-evolution Kershaw, allowing just two hits over six innings with a walk and eight strikeouts despite breaking 91 mph on his heater exactly twice. One of those two hits happened to be an Eduardo Escobar two-run bomb, so Kershaw was left decisionless, but it was an ace-caliber outing all the same.

Even with his ERA slightly inflated by a one-inning, four-run stinker opening a doubleheader in Chicago early this month, Kershaw is showing no signs of slowing down any further. He’s gone six-plus innings in seven of 10 starts, giving up one or zero runs in four of them. He’s seen another strikeout bump, keeping pace with the rest of the league by moving his K rate above 29% for the first time since 2017. On the whole, a bit less than a third into his 14th MLB campaign, Kershaw is already in his usual place near the top of the WAR leaderboard, even if he doesn’t easily pace it like he would have a half-decade ago.

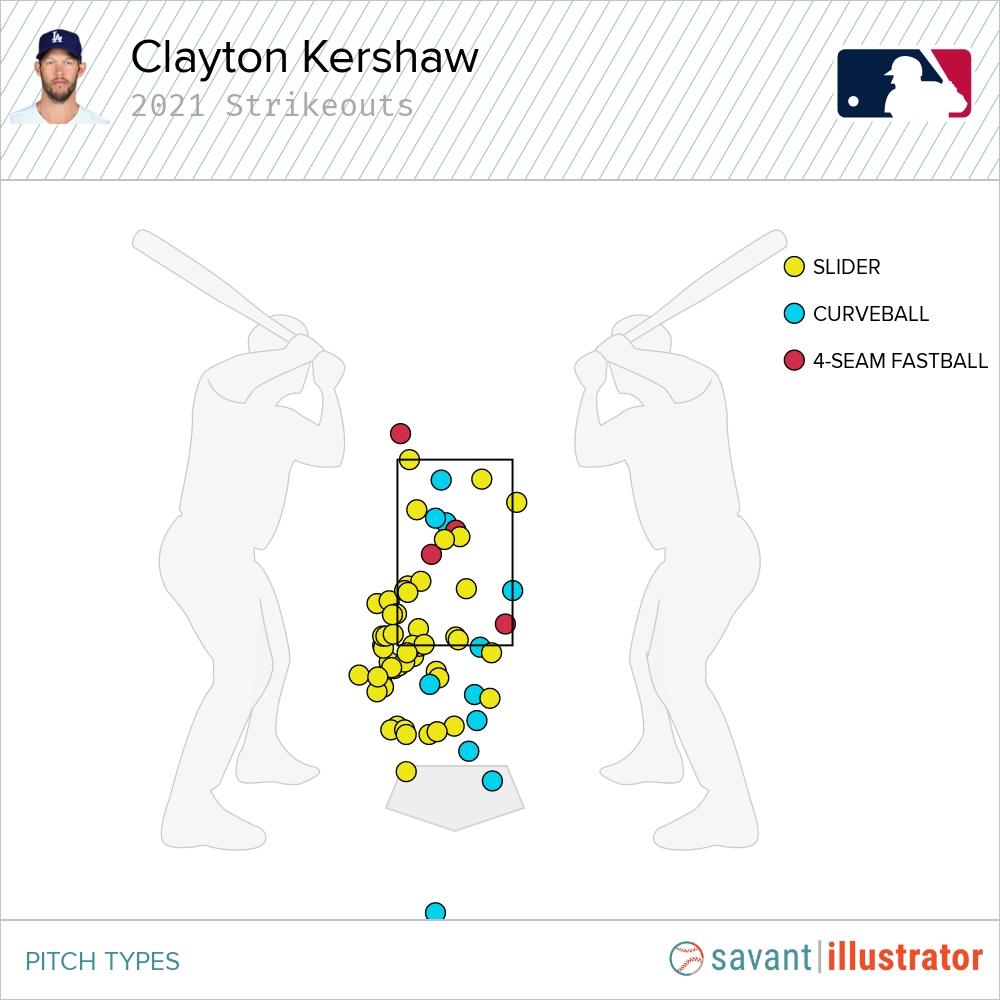

Given that WAR is a counting stat, simply maintaining such an elite baseline is pretty impressive at age 33 with more than 2,500 pro innings under his belt. I said that Kershaw is constantly evolving, and this year is no exception. Peep all eight of his strikeouts from Wednesday and see what you can see.

Oh yes! Sliders galore! And a couple Hall-of-Fame curveballs for good measure. Not a single fastball in sight, just vibes. And it’s not an isolated trend, either. Here are all 65 of Kershaw’s strikeout pitches on the season.

Where have all the fastballs gone? To a better place, apparently. Kershaw’s four-seamer hasn’t held the velocity bump it saw last year — that may have been just a seasonal illusion, anyway — so despite having near-perfect rise, it’s been hit worse than ever, to the tune of a .403 xwOBA.

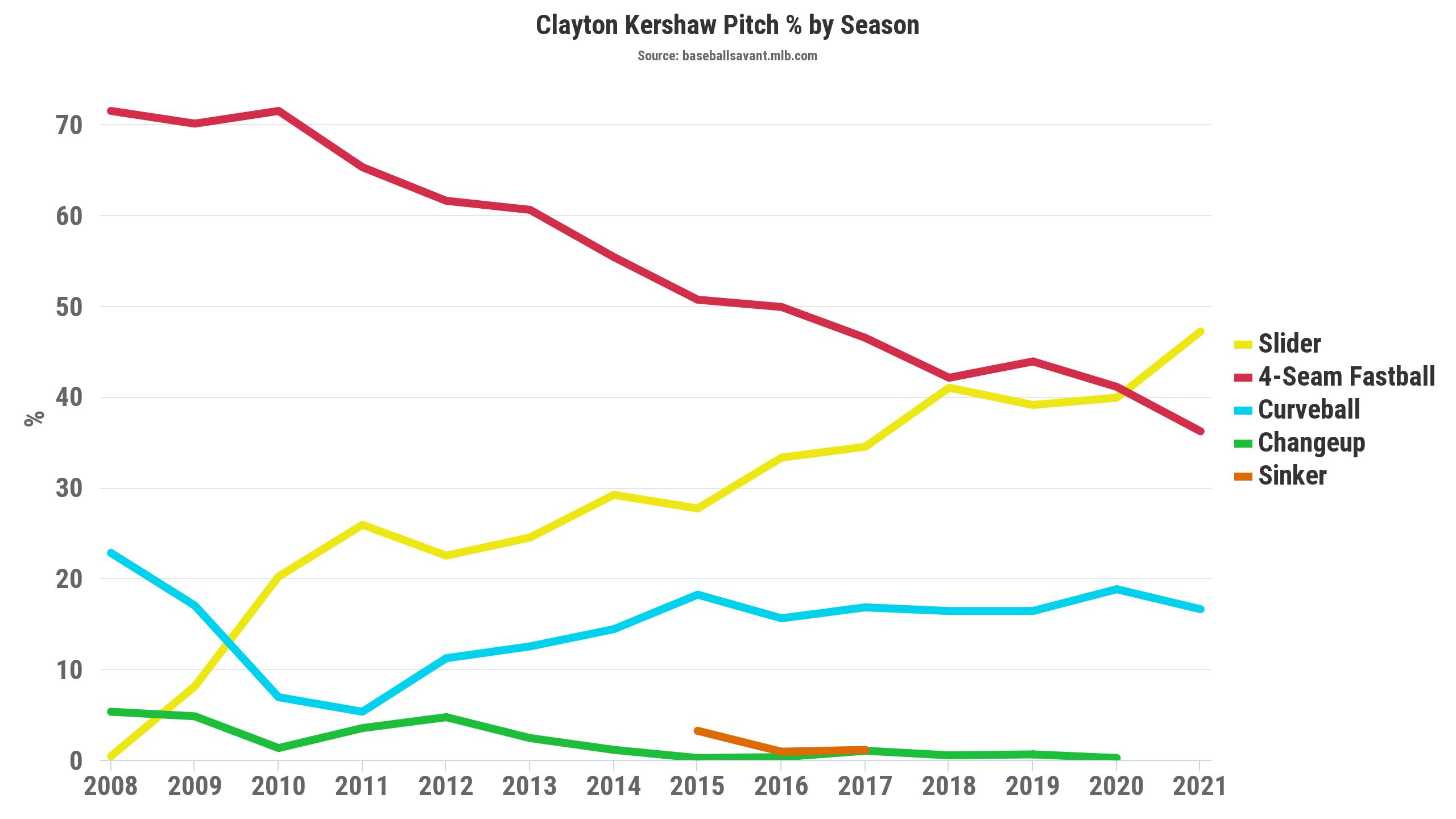

Perhaps recognizing that the fastball’s diminishing returns aren’t likely to improve at this stage of his career, Kershaw has taken the plunge towards making his slider his primary offering, bringing to a conclusion the journey he started when his velocity first began to plummet.

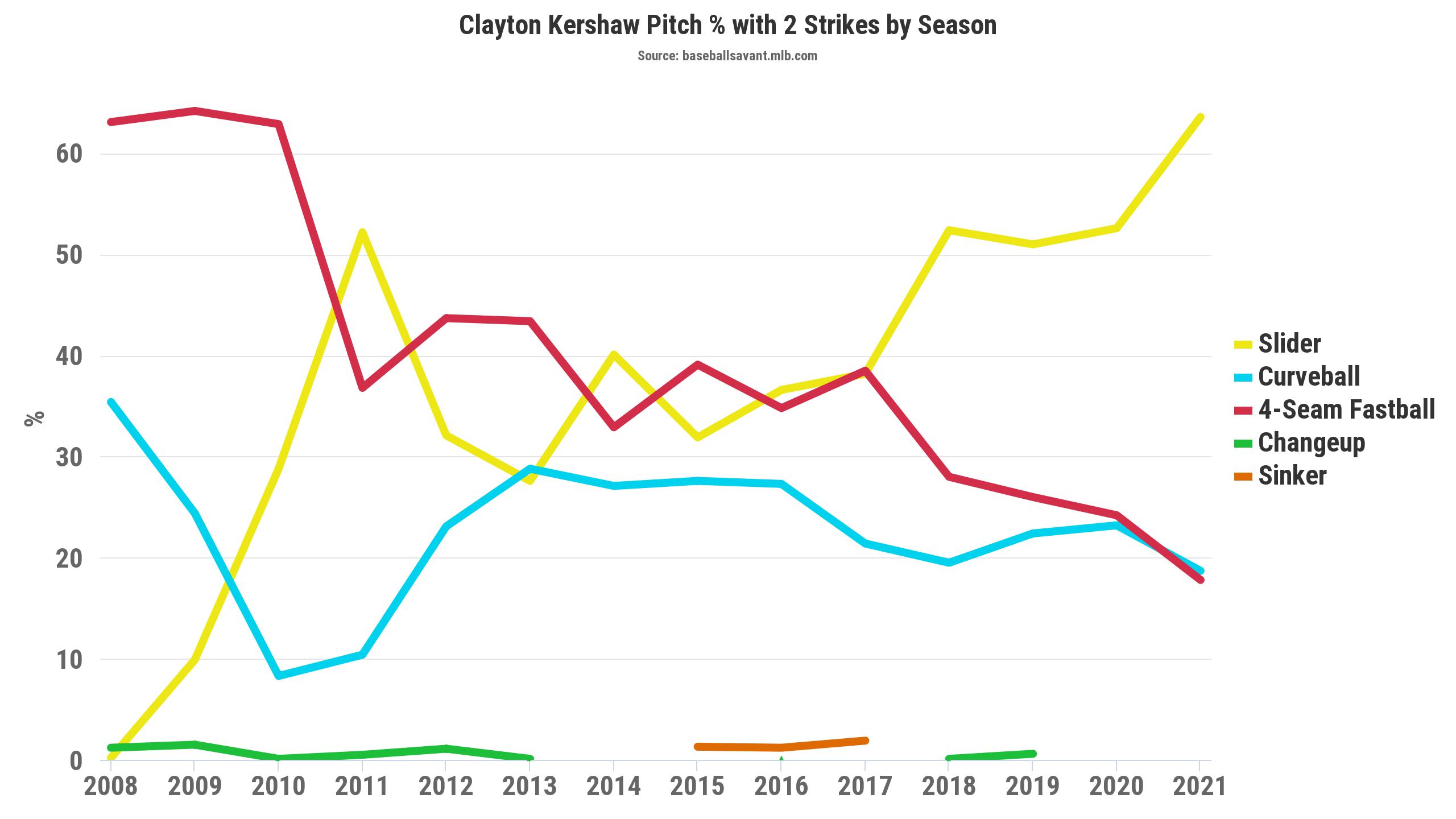

Meanwhile, that strikeout chart makes a lot more sense when you see that Kershaw’s reliance on the slider with two strikes has spiked even further, throwing it nearly two-thirds of the time when a strikeout is on the table.

Estevão Maximo first identified this trend last month in their post on the FanGraphs community blog, noting the extreme dip in fastball usage through Kershaw’s first four starts. He hasn’t slowed down since then, with his slider usage settling in among the heaviest in the league through two months. In fact, among starting pitchers, nobody at all throws sliders at a higher rate.

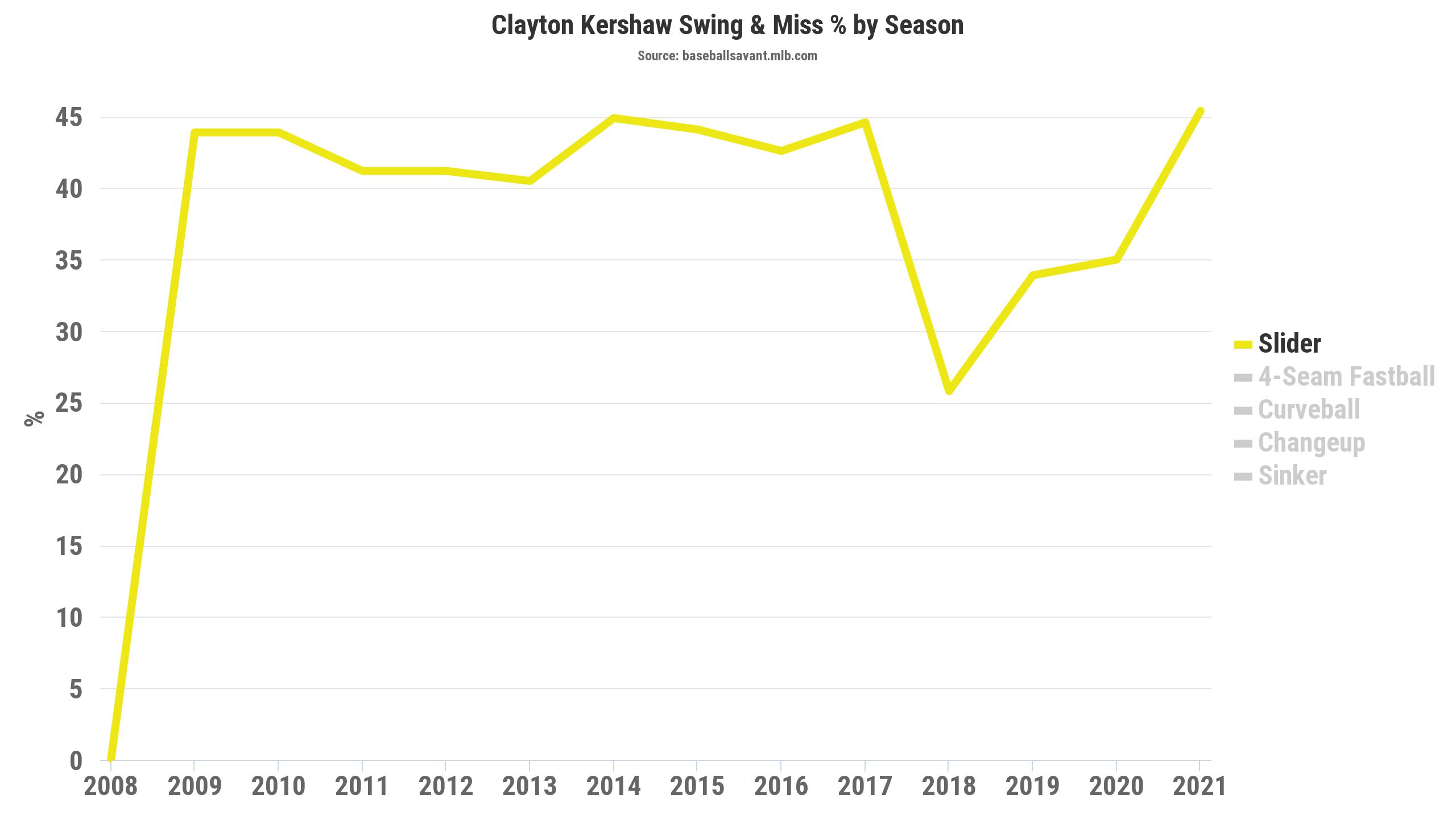

Increased slider usage has been the steady adjustment he’s made over the course of his career because his slider was, for the most part, elite. It ran into some trouble in recent years, though, with its whiff rate cratering to a 25% nadir in 2018. Many people smarter than me pointed to the decreasing separation between the fastball and slider as the source of the latter’s woes, but even though the separation hasn’t gotten any better, the slider definitely has. Now, it’s once again missing bats at an elite rate, but this time with the heavy usage of a fastball.

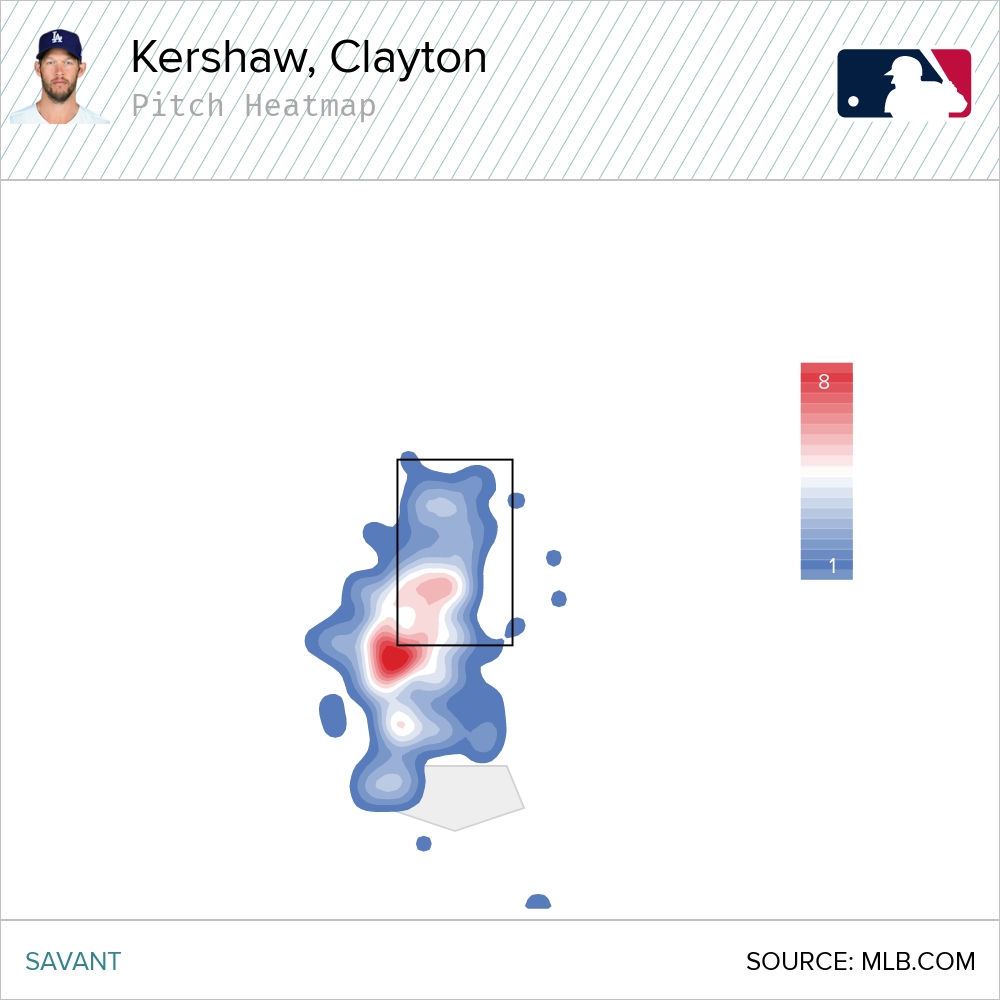

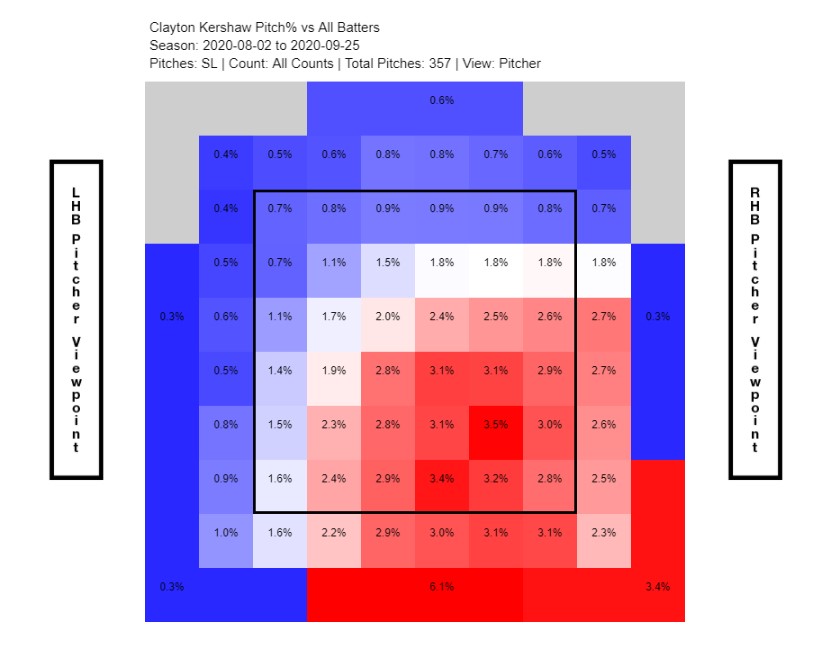

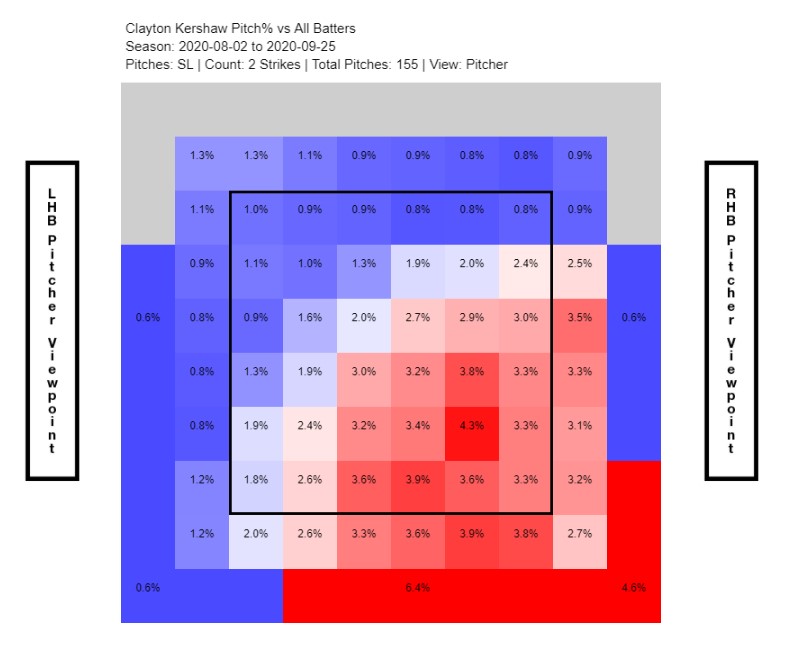

What’s behind the rejuvenation of the slide piece? It’s hard to say. The first instinct is to check location, and it doesn’t seem like Kershaw is locating the pitch too much differently than in the past.

|

|

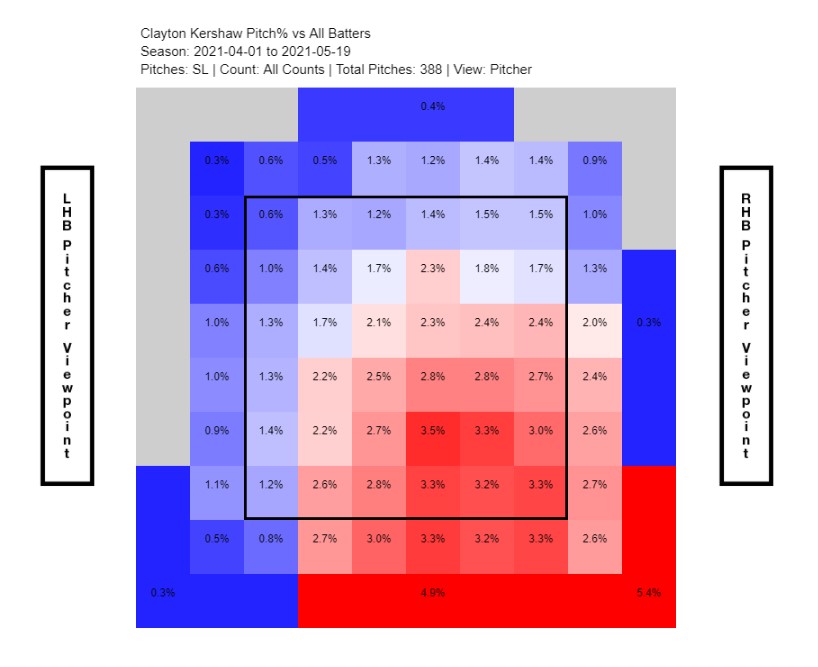

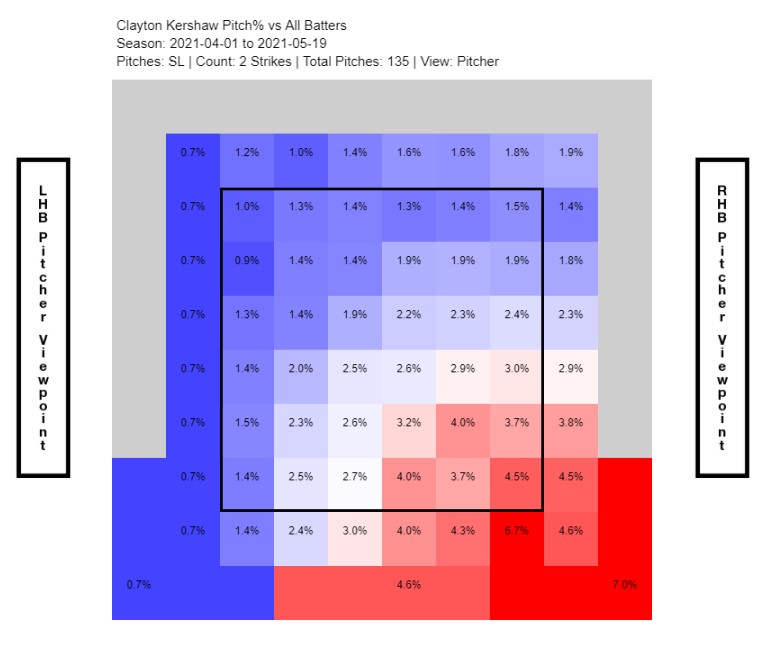

So that ain’t super helpful. A look at his chart with two strikes, on the other hand, helps clear up why the pitch has been able to nail the rare combination of high use with effectiveness.

|

|

Now we’re talking! Hitters are still swinging at his slider at the same rates, but he’s simply doing much better at putting it out of the zone and out of reach. Baseball Savant’s heatmaps make the precision he’s using with two strikes even clearer. At 136 pitches, this isn’t a tiny sample size, either.

Looking at this season, you couldn’t draw up a more perfect slider location if you tried. With a righty in the box, it’s simply unhittable. A lefty might have a chance, but even if they know it’s coming and they’re able to track it well enough to sit back and put a barrel on it, the nature of the pitch makes it nearly impossible to pull.

It’s also a tough location to consistently execute because if you miss to one side, you’re right down the middle, and if you miss to the other, you’re kneecapping a righty and giving a lefty an easy take. That’s part of what makes Kershaw Kershaw, though. Even with that curveball and a solid slider, it would be impossible for a 90 mph heater to carry a pitcher to those kinds of results without impeccable command, and that’s probably a solid part of the answer here. Kershaw can get away with throwing the slider that much without diminished returns because his command of the pitch is probably as good as any in baseball, and this season, he’s figured out how to consistently throw it exactly where hitters straight-up can’t do anything about it.

As far as answers go, location and command are a bit boring, because they’re difficult to quantify (though it would be great if Eno Sarris and Max Bay ever open up their black boxes of Command+, Stuff+, and Location+ someday), and also, in this case, because they don’t seem that different. Even if it wasn’t ideal, his location wasn’t exactly poor before this season. But looking at the slider’s physical properties tells more or less the same story.

All in all, these are real changes, but they’re not super visible to the TV eye, and it’s fair to question whether they make for any tangible difference.

It looks like it might be a tiny bit sharper, but the camera angle is also slightly different, and having watched a bunch of them, I didn’t notice much else to speak of.

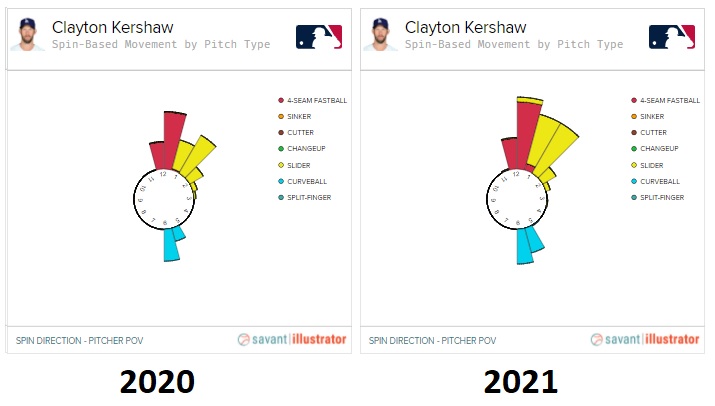

The lack of significant alterations is even more baffling because if anything, his slider is once again losing separation relative to the fastball. In terms of vertical movement, the 13-inch gap between the two isn’t quite as bad as 2018, when it got down to just 10%, but it’s still the second-smallest of his career. It’s lost a touch of glove-side movement, though not enough to sweat over, and it’s spinning more or less the same in 2021 as it was in 2020 (while it’s possible to get estimates for spin direction and active spin prior to 2020, these aren’t nearly as accurate and probably shouldn’t be put on the same scale).

Movement and velocity aren’t the only way his slider is resembling his fastball a tiny bit more. That tiny little change in average spin direction is probably meaningless, but it does make it a little bit more upright, moving slightly towards his fastball, which spins at an almost completely vertical 179 degrees (i.e, pointing straight at the 12 on a clock face). You can kind of see it in this Savant illustration. It’s subtle, but you can see the slider’s center of gravity, so to speak, moving a little bit more in line with the four-seamer’s.

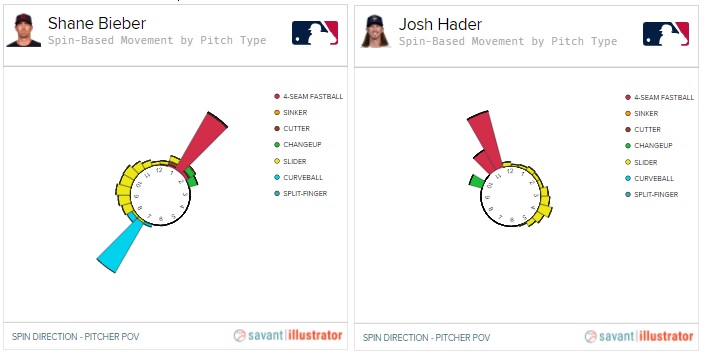

Even if you can’t really see it — and you’d be forgiven for not having stared at these things long enough to notice — these charts highlight something else interesting. If one wanted to criticize the previous paragraph, there’s a valid argument that average spin direction doesn’t actually tell us anything about a slider, because so much of it is gyro spin that’s going to point all over the place. But one thing we can see in these illustrations is that the 48% active spin that makes up the last column of the chart is unusually high for a slider. Not, like, absurdly high. But it’s 70th out of 350 qualifying sliders, high enough to make a mental note of. The less gyro on a pitch, the smaller the deviation in spin direction, the more tightly clustered the bars are on that graph. For example, this is what Shane Bieber and Josh Hader’s gyro-heavy sliders look like on the same chart.

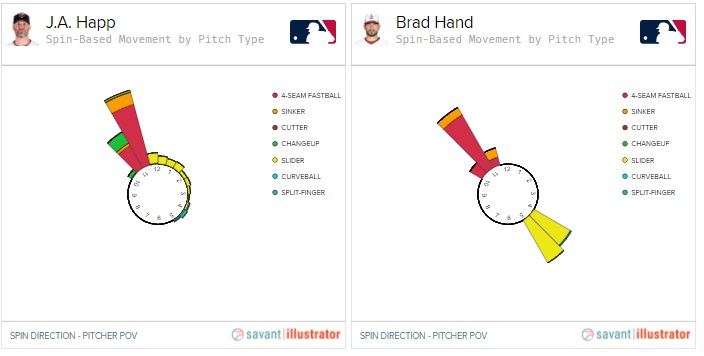

Of course, those are massive outlier pitches. But the lack of consistency on the yellow bars indicates the limited usefulness when it comes to average spin direction and sliders. For some more pedestrian examples, see how the scattershot distribution of bars on J.A. Happ’s 30% active spin (70% gyro) slider, and how Kershaw’s chart much more resembles that of Brad Hand’s 65% active spin slider, though with a totally different direction.

I only go through this very tangentially related lesson on sliders and spin direction to hint how Kershaw’s doesn’t quite follow most of the normal rules. As I referenced earlier, much has been made of the reduced velocity gap between his slider and fastball, but that actually undersells how extreme it is — it’s the smallest in baseball by a fair margin.

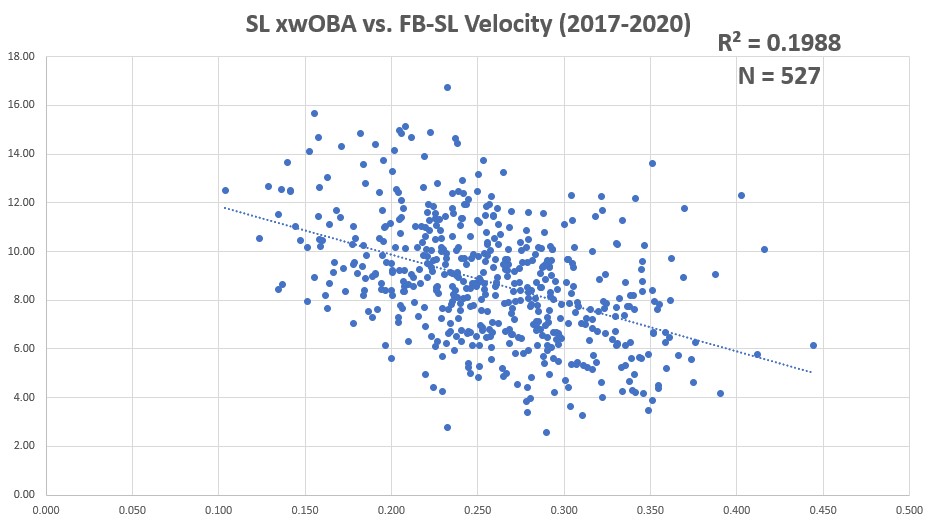

This isn’t one of those cases in which Statcast shows us where conventional wisdom is flawed. Just this morning, Ben Clemens published a second part of his fascinating deep dive into large-scale slider data, and while his findings do muddle conventional wisdom somewhat, they also tell us unequivocally that having a small velocity gap between the fastball and slider is not a good thing, no matter what other context you include. Logically, there should be a strong relationship between velo differential and contact quality. The more you can mess up a hitter’s timing, the worse their contact will be, if they make contact at all.

Some back-of-the-napkin math backs up this idea. I took every individual season from 2017-2019 in which a pitcher threw both 200 sliders and 200 four-seamers, and plotted their slider’s expected wOBA based on launch angle and exit velocity (i.e., contact quality) against the velocity differential between the two pitches.

Running a simple one-variable regression isn’t enough to make a conclusive statement on anything. Still, an r-squared of .20 (meaning 20% of the variation in xwOBA is explainable via velo difference) is a much higher value than I originally anticipated, considering how granular of a stat pitch-specific xwOBA is and how many different elements go into a “quality” slider.

Again, this is much too simple of a test to be able to say anything with certainty, but it’s enough to make me satisfied that I’m not losing my mind, and that there’s something quite wonky about Kershaw’s pitch. Even without labels, you can probably pick out his 2018 and 2019 seasons. They’re the two bottom-most dots, pretty dang isolated from the rest. Point being, when you put all this stuff together, it’s clear that this particular slider doesn’t operate by the normal rules, even if the normal rules are typically correct.

So I’m almost 2000 words in, and I realize I’ve been thinking about this all wrong. If this were someone else’s slider, I’d probably be right to ask how it’s finding success despite its undesirable tendencies. But this is Clayton Kershaw. Clayton Kershaw is an outlier, and so is his slider. Outliers sometimes require outlier logic; what if Kershaw’s slider is doing well because it’s really similar to his fastball?

Velocity separation is great, but tunneling is also great. One way to compensate for a smaller than average velocity gap is to lean into the similarity and try to make them look as similar as possible for as long as possible. The name of the game is to keep the hitter guessing. If a pitch is super nasty or has solid velocity differential, sometimes it doesn’t matter if a hitter recognizes a pitch — they can’t hit it anyway. But if neither of those two elements is present, the only way to get a hitter to miss is to make it so that they don’t know what pitch they’re getting until it’s literally too late. Hand in hand with his excellent command, that appears to be exactly what Kershaw is doing successfully.

Clayton Kershaw, 93mph Fastball and 89mph Slider, Individual Pitches + Overlay (with and w/o tails). pic.twitter.com/uPN2Y7n2kE

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) October 20, 2020

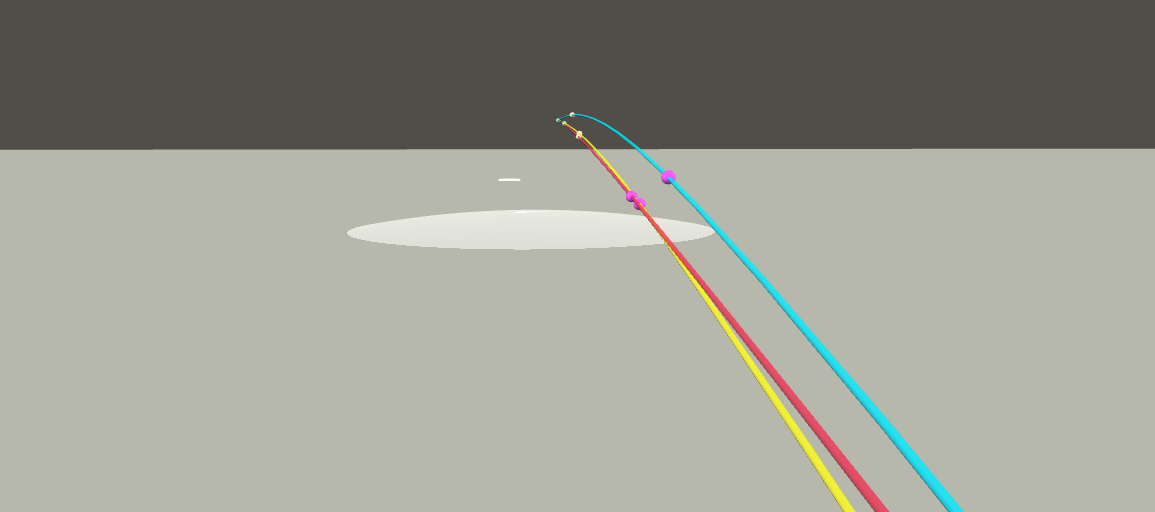

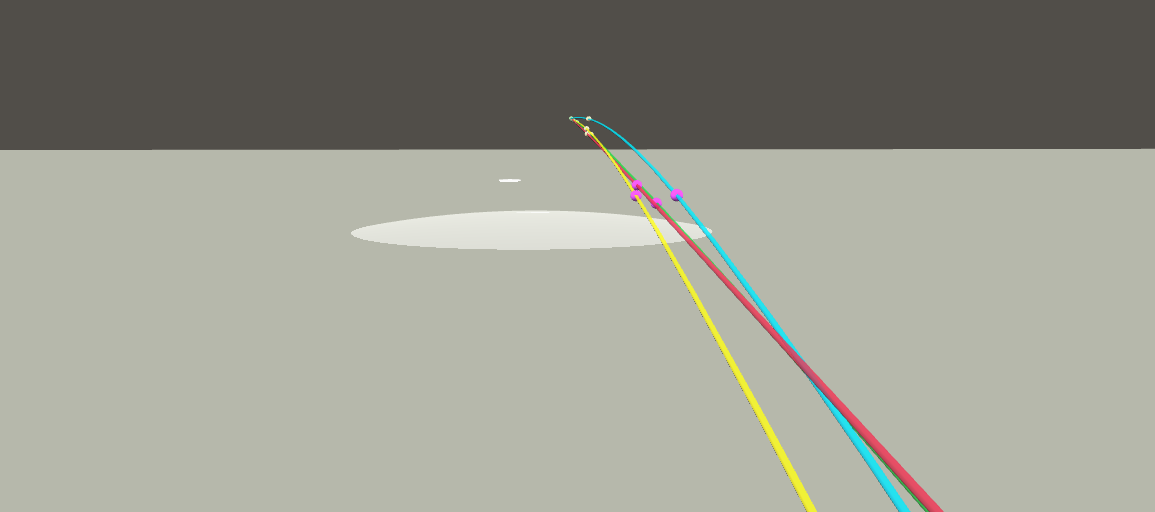

Thanks to the magic of Savant’s illustrations, we can also visualize what the “until it’s literally too late” part looks like. This view is from the eyes of a right-handed hitter, and the little purple ball represents the hitter’s “commitment point” after which it’s physically impossible for the brain to process information fast enough to make an adjustment. As with the rest of Savant’s visuals, red is fastball, yellow is the slider.

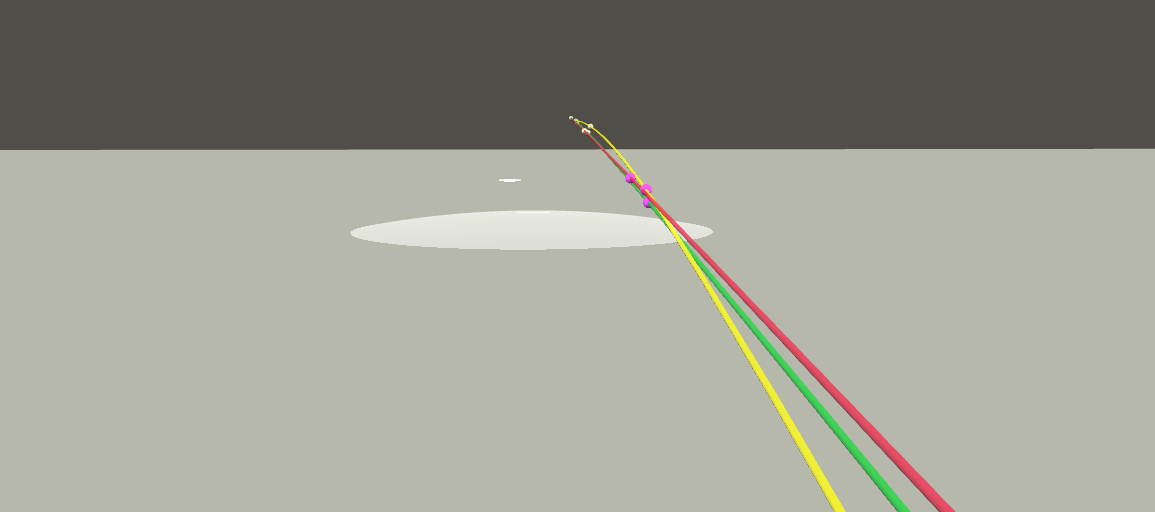

Not only are the pitches very close out of the hand and virtually indistinguishable at the commitment point, they remain tight for a considerable distance after the moment in which a hitter must decide what they’re doing. Rob Friedman’s eye test wasn’t wrong; these two pitches are incredibly difficult to tell apart. More context also illustrates the first point — that tunneling doesn’t matter if you’ve got nasty movement. Here’s the same view of Carlos Rodón’s deadly fastball/slider combo.

It doesn’t matter that Rodón’s slider is fairly distinct from his fastball. It’s close enough, and the pitch has such deadly glove-side movement that when it’s in the right spot, hitters are completely helpless. Blake Snell, meanwhile, has relatively pedestrian movement on his slider, but the velo gap is right in the ~8 mph sweet spot that Clemens found in his article, and while he doesn’t do quite as fantastic of a job as Kershaw at tunneling, it’s good enough that the pitch still plays as one of the game’s best when it’s on.

If tunneling doesn’t feel like an adequate explanation for why Kershaw’s slider is suddenly playing up, I don’t blame you. Similar to the command, it’s not like he was bad at tunneling in the past, either. It’s also very fair to argue that the spin stuff is completely irrelevant because it honestly might be. There’s no clear explanation here! Pitching is truly a game of inches, and as powerful as Hawkeye cameras are, there are inches out there that we’re not able to fully measure yet. Some advanced pitch models don’t even think that the two pitches are all that similar—I could be even more wrong than usual here!

As per that usual, this has been a long exercise in concluding with an enthusiastic “I don’t know!” None of those things by themselves seem to be enough to explain why a pitch that by all tenets of conventional wisdom should be getting lit up is among literally the most effective in the game.

Only four pitches in baseball have a SwSt above 25% (min 200 thrown):

Bieber SL: 28.9%

Kershaw SL: 28.3

Gausman FS: 28.3

Means CH: 25.6— Alex Fast (@AlexFast8) May 18, 2021

At the same time, none of those things have to explain it all by itself. These are all subtle changes, and when baseball isn’t a game of inches, it’s a game of millimeters. This current iteration of Kershaw has only been active for a few years now; as recently as 2017 his heater was still breaking 94 mph with some regularity. If there’s anything conclusive in this article, it’s that in a vacuum, whatever route to success Kershaw’s slider takes is both weird and narrow. It may just be that it took a while to adjust, and now, with superlative command and a few other things going his way, Kershaw has figured out how to walk a much thinner tightrope while still being Clayton Kershaw.

It could fall apart at any second — such is the nature of narrow tightropes — but that’s still who he is. Even as he was forced to start from square one with his slider, he’s steadily built it up for three consecutive years, and even though it operates quite differently in relation to his other pitches than it did in 2015, it’s producing just as dominantly. Maybe the characteristics of the pitch are irrelevant. Maybe Kershaw just needed a little more time to figure out how to be himself again.

Photo by Jon Durr/Getty Images | Adapted by Aaron Polcare