Brandon Workman pitched 209.2 major league innings from 2013 to 2018. Some of them were starts, some of them were in relief, and most of them weren’t great. So you can imagine my surprise when Workman posted a 1.88 ERA and 2.1 WAR in 2019, given that those numbers are a far cry from the 4.38 ERA and 0.8 WAR he’d amassed previously. Obviously, there’s plenty of room for some healthy skepticism and I am ever the skeptic.

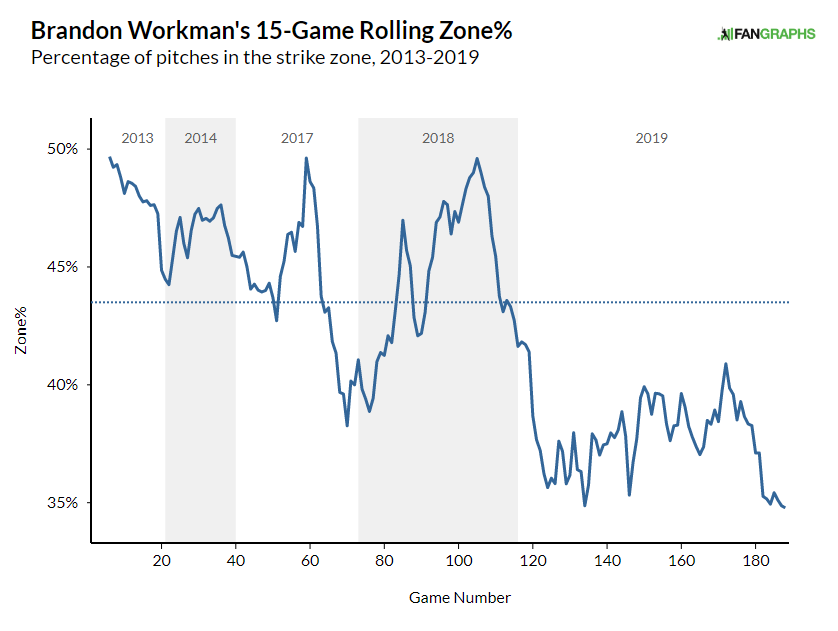

There are a few reasons why I think it will be interesting to watch Workman over time, as he’s leaned into quite an interesting approach. The first of which Tony Wolfe of FanGraphs has touched on, and that’s that Workman has really allowed himself to throw outside of the zone.

Of course, this doesn’t come without its own pitfalls—his walk percentage jumped from 9.6% to 15.7%. I don’t need to reinvent the wheel here, as Wolfe already touched on these changes, but Workman started elevating his fastball more above the zone (which nearly doubled his swinging-strike percentage) and he also started throwing his curveball and cutter out of the zone more as well. From a pitch tunneling perspective, it’s not an easy feat to lay off of his three offerings, so it will be interesting to see how teams approach him moving forward. In any case, his strikeout percentage also increased by more than 14% to 36.4%.

What’s interesting is that Workman has made a trade-off of sorts:

| SwStr% | Called% | CSW% | Ball% | In Play% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 10.2% | 20.8% | 31.0% | 38.6% | 17.6% |

| 2019 | 12.8% | 20.9% | 33.7% | 40.1% | 10.9% |

Everything is largely the same. The most discernible change, though, is that Workman has significantly reduced the number of balls that he allows into play. Of course, you likely don’t have a frame of reference for what percentage of balls any given player allows into play. In 2018, Workman ranked in the 51st percentile—he was nearly league average, by definition. In 2019, though, Workman dropped into the 1st percentile, as just eight pitchers (of 707) allowed a lesser proportion of balls into play than Workman. The trade-off here, then, is that Workman threw out of the zone more—which led to an increase in CSW and ball percentage—but it also led to a newfound ability of not letting hitters put the ball in play.

The question we’re going to want to ask is if this is sustainable. There are two things to look at: (a) can Workman keep preventing hitters from putting balls in play, and (b) given Workman’s poor swinging-strike percentage, can he limit hard contact?

Something that shouldn’t go unnoticed is that, even after an elite relief season, Workman is rather undistinguished in terms of drawing whiffs. Despite his gains with his fastball this year, he ranks in just the 71st percentile in overall swinging-strike percentage. As a supposed elite reliever, that may not be very inspiring, but I’m cautiously optimistic. He’s shown the propensity to earn called strikes as very few pitchers can. Workman’s 20.8% called strike percentage in 2018 is nearly identical to his 20.9% called strike percentage in 2019. This ranks him in the 97th percentile in called strike percentage, so perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that he ranks in the 97th percentile in CSW since 2018 as well. This leads me to believe that this is more of a skill than a blip. Perhaps my pessimism was all for naught.

After all, Workman is one of the most deceptive pitchers in baseball:

| O-Swing% | Z-Swing% | Z – O-Swing% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sergio Romo | 40.5 | 63.6 | 23.1 |

| Ryan Pressly | 40.6 | 63.8 | 23.2 |

| Adam Morgan | 40.3 | 63.7 | 23.4 |

| Chaz Roe | 27.6 | 51.4 | 23.8 |

| Brandon Workman | 30.0 | 54.1 | 24.1 |

| Jimmy Cordero | 41.2 | 65.7 | 24.5 |

| Andrew Kittredge | 42.6 | 68.1 | 25.5 |

| Stephen Strasburg | 37.2 | 62.8 | 25.6 |

| Aaron Nola | 33.5 | 60.4 | 26.9 |

| Chris Sale | 35.1 | 62.1 | 27.0 |

No other pitcher aside from Chaz Roe gets fewer swings in the zone than Workman. That’s where he makes his money. He doesn’t need to make you chase at an elite clip like Ryan Pressly. He’ll simply make you take a pitch for a strike instead, or blow a fastball by you.

Thinking back to Wolfe’s article on Workman (as well as my own thoughts above), he is simply pitching to more optimal locations. To answer the second question above (i.e., can he limit hard contact?), I think Workman should be able to continue to do so, albeit not at this rate. Here’s how:

First, it’s no surprise that his curveball induced weak contact. It was a ground ball pitch in 2018, and it remained a ground ball pitch in 2019. Throwing it out of the zone more only made it more difficult to barrel up.

In elevating his fastball, Workman converted a lot of the batted balls that were fly balls in 2018 into pop-ups in 2019. This may not be completely sustainable—some of those will likely turn back into fly balls (and, as it follows, home runs)—but it stands to reason that as he elevated his fastballs above the zone, hitters got under them too often. This is going to be the most decisive pitch for him. He allowed a 13.3% barrel percentage on his fastball in 2018 and didn’t allow any barrels with it in 2019. His true barrel percentage is likely somewhere in the middle, but if he keeps locating his fastball at the top of the zone, he could feasibly keep it on the lower end.

Then there’s his cutter. Since 2017, its ground ball percentage is 56.5%, and with 83 batted ball events, we can start to be a little more confident that this is a legitimate ground ball pitch. Over his career, he’s gotten into trouble with his cutter when it’s leaked over the plate middle-middle, or to his arm-side. This year, he honed in on the outside part of the plate against righties like never before. And, again, from a pitch tunneling perspective, if hitters are expecting his cutter to be a fastball at the top of the zone, they’re going to swing over it as it darts down and away out of the zone. That should mean lots of ground balls.

Overall, what you now have are three pitches that induce extreme batted balls as it pertains to launch angle. His fastball induces pop-ups, and his cutter and curveball induce ground balls, both of which are amongst the most favorable batted ball types in baseball. It remains to be seen if his fastball can avoid being lit up or if his cutter can continue to be a ground ball pitch. But if they do, Workman has the recipe for limiting hard contact—and sustainably!

Of course, I have to present the other side of the coin. And the other side is that Workman’s entire 2019 was just a blip. I’m not convinced that this is true, mostly because we have substantive changes (and we can track those changes to his results), but that doesn’t mean that the two are mutually exclusive. Workman could have gotten legitimately better and he also could have had a lot of good fortune (or luck, if you want to call it that).

As I’ve done in the past (as I’ve learned from Alex Chamberlain), I’ll take a look at Workman’s wOBAcon and xwOBAcon at the pitch type level to see just how sustainably he may be able to keep up his performance. After all, he ranked in the 90th percentile or better in hard hit percentage, expected batting average, expected slugging percentage, barrel percentage, and xwOBA. That reeks of regression to me.

First, we’ll compare Workman’s wOBAcon and xwOBAcon:

| wOBAcon | xwOBAcon | |

|---|---|---|

| Four-seamer | 0.256 | 0.315 |

| Cutter | 0.110 | 0.316 |

| Curveball | 0.232 | 0.312 |

Already, we can see that Workman overperformed wildly with his cutter, and he was fortunate with his four-seamer and curveball too. This doesn’t come as much of a surprise, given that his overall .213 wOBAcon and .314 xwOBAcon. Paired with the disparity between his 0.7% barrel percentage and 4.2% deserved barrel percentage, we should see some regression coming, but that’s already a given. We knew with his 1.88 ERA this wasn’t going to persist considering his 2.46 FIP and 3.33 xFIP.

Next, here is how Workman’s pitch type numbers compare to their respective league averages:

| xwOBAcon | xwOBAcon (Lg) | |

|---|---|---|

| Four-seamer | 0.315 | 0.402 |

| Cutter | 0.316 | 0.359 |

| Curveball | 0.312 | 0.356 |

As we just saw, we should see Workman’s pitches all regress from their wOBAcon to xwOBAcon, but there may be even more regression to be had. While he could reasonably repeat his cutter and curveball numbers, it’s unlikely that he can sustain his fastball’s wOBAcon, and we shouldn’t expect Workman to be the exception to the rule until he proves he is. In any case, I think it’s clear given the previous two tables that we should see some form of regression, but given the nature of statistics, that is not to say that we will see any regression.

As a former Workman detractor, I can say that I came into this article expecting to sour even further on him. What’s happened is the opposite; I remain dubious as it pertains to Workman’s batted ball numbers, but I’ve become more optimistic about his ability to continue to succeed because of his penchant for earning called strikes, paired with the improvement of his fastball.

Workman doesn’t throw his fastball in the zone a ton, so his curveball is going to need to do a lot of the heavy lifting. Either way, he’s relying on a unique (albeit risky) approach. If we take a step back, I think that—given his gains in K-BB%, paired with his ability to ostensibly induce weak contact—we may be looking at something vaguely resembling a nearly elite-level relief pitcher. He may not go about it in a traditional manner whatsoever, but I think that’s the thing that I love the most about Brandon Workman.

(Photo by John Cordes/Icon Sportswire) | Feature Graphic Designed by James Peterson (Follow @jhp_design714 on Instagram & Twitter)

Great article. I took Workman in my draft. I have some concerns about facing both the AL and NL East during this short season and the parks he’ll have to pitch in. Will you share you thoughts on what you realistically expect ratios, K% and BB% will be in your opinion?

You can put me down for a 34 K%, 13-14% BB%, and maybe a 2.50-3.00 ERA and 1.10-15 WHIP?

Who would you rather have – Edwin Diaz or Workman?

I’m taking Workman for the floor. I think Diaz’s down year had to do with losing his feel for his slider because of the changed composition of the ball (and so I see him improving this year), but Workman should be the safer option. It’s basically floor versus ceiling here, but Workman isn’t without his own upside.