The former Major League catcher entered Italy in a submarine with a .45 caliber pistol and cyanide capsule in his pocket, ready to deliver a crippling blow to the Axis’ attempts to build the Atomic Bomb. Moe Berg could generously be called an average ballplayer at any point during his 15-year career.

He never played in more than 100 games in a season, scattered only 441 hits featuring 6 home runs over that time, and finished up with a .243 lifetime batting average. In 1929 did he received two votes in the balloting for MVP in the American League, but baseball was clearly just the tip of the iceberg for him.

“Brainiac” he was called or “The Professor” for graduating from Princeton and his proficiency in a dozen languages, Moe Berg is the only Major Leaguer to have earned a Medal of Freedom, but also spent the last years of his life changed from his wartime experiences. Some say Berg’s entire baseball career was purely a cover for his spycraft and Casey Stengal called him “the strangest man ever to play baseball”. Whatever the case it was a life full of baseball, adventure, and consequences.

Moe Berg: Ballplayer

Moe Berg was a seemingly normal kid growing up. The son of Jewish immigrants from Ukraine, his father pressured him to study, but Berg did what kids tend to do and ignored his parents’ wishes. Instead he played baseball with other kids on the streets of 1900s New York.

That’s where a cop walking by watched a young seven-year-old Berg play and invited him to join the Methodist Episcopal Church team. It was a little problematic for a young Jew to play with a team of Catholics, so Berg went by the name “Runt Wolfe” during this time.

After excelling in high school in both baseball and academics (to his father’s joy), Berg joined the Princeton team where he hit .375 and was routinely heralded as a smooth shortstop with a cannon for an arm. He soared under pressure, hitting well over .600 against the rivals of Yale and Harvard.

His aptitude in the field continued to be matched by his performance in academia. Berg majored in Romance Languages including German, Greek, Italian, Latin, Spanish, and Sanskrit – performing so well that his thesis could be found for a time at the Library of Congress.

Berg enticed scouts with his exceedingly large frame for a shortstop – Berg would later boast about being the tallest shortstop in the Majors – and his easy swing. So much so that the Brooklyn Dodgers (then the Robins) signed the young player a day after Princeton played an exhibition against the Detroit Tigers.

In his debut the same day he signed, Berg swatted a single in his first at-bat and came around to score. While he was advertised as a sure-fire fixture at short, the shine of his debut quickly wore off. In an August game – batting in the doldrums of the .100s to boot – Berg cost staff ace, Dazzy Vance, a shut-out with a throwing error to third.

His arm was never questioned, but his flaws at the plate were being utterly exposed by Major League pitching. The Brooklyn Daily Times put it bluntly:

His stance seemed all wrong and it was seldom that he met a ball squarely, his drives all lacking the snap and zip of big league bingles. In the expressive parlance of the ball players, he was “hitting at the dirt.”

The rookie put up a dismal .188 average over 50 games with only 2 walks at the end of the ’23 season, earning himself a demotion to the minors. A scouting report on the young man that year established the famous line, “Good field. No hit.”

Instead of honing his swing or working on his eye that offseason, Berg enrolled in 32 classes at Sorbonne University in Paris to study Latin. Whatever he did worked, because his batting average jumped to .311 in the minors and he once again began to wow crowds again with his glovework, even being called “the best throwing shortstop in baseball today”.

The White Sox picked up Berg’s contract to play catcher for the 1926 season – but in Moe Berg fashion he showed up to Spring Training late so he could finish up his first year at Columbia Law School. From the 1926 season until his retirement in 1939, Berg never again touched the Minor Leagues.

This isn’t to say Berg completed the story and lit the league on fire, far from it. He only played in more than 100 games in a season once, his single season-high for home runs was 2, and he ultimately put up a negative WAR for his career.

But it wasn’t his play that made him stand out to his peers.

Moe Berg: Brainiac

Either Casey Stengal – or Ted Lyons – or someone else entirely said of Berg, “He could speak 12 languages but he couldn’t hit any of them.” The catcher arrived late again to the 1927 and ’28 seasons to finish up law school and passed New York’s bar exam in 1929. He was an eclectic character in the dugout, but a character that teammates recognized as some shade of brilliant.

A rookie Ted Williams said of Berg:

Is he some kind of an act of what, but I concluded that here was some kind of different human being. He was absolutely unique in baseball and he certainly had a real man’s guts.

The greatest hitting mind baseball would know peppered the veteran Berg, having caught against legends like Gehrig and Ruth, Berg gave Williams his thoughts on those hitters and the youngster, “Gehrig would wait and wait and wait until he hit the pitch almost out of the catcher’s glove.

As to Ruth, he had no weaknesses. He had a good eye and laid off pitches out of the strike zone. But you are better than all of them.”

While still playing backstop, Berg became a regular on the NBC radio show “Information Please” answering questions from everything from physics to mythology to astronomy. He championed the Jeopardy-esque program but suddenly walked off the show after many episodes when the host asked too many personal questions.

His fame for his wide breadth of knowledge was probably greater than being a Major League catcher. When once a person chided Berg and asked why he isn’t using his intellect for something more than baseball, Berg quickly responded, “I’d rather be a ballplayer than a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court.”

After the 1931 season, Berg was traded to the Washington Senators. While Berg played well for his standards with the team, it was the social life of the nation’s capitol where Berg excelled. He was a “womanizer,” and “very charming and the women went ga-ga for him” but doing so “with grace and elegance.” He became so entrenched with the DC social and diplomatic life that he reportedly kept a tuxedo in his locker to attend functions after games.

It was in those high society gatherings that Berg attracted the attention of members from the new Roosevelt administration that began directing his ambitions.

Perhaps with that diplomatic ambition in mind, he was chosen along with teammates Ted Lyons and Lefty O’Doul in 1932 to teach baseball seminars in Japan at universities. Berg, of course, signed his name in Japanese on baseballs and stayed behind to tour Asian countries while his teammates returned home. This trip overseas was just Berg dipping his toes gently into international affairs before jumping in with abandon.

Moe Berg: Spy

The Major League All-Stars would tour Japan two years later in 1934 and play against local teams in friendly exhibitions. This team consisted of names like Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Lefty Gomez, and auspiciously, Moe Berg who was decidedly not an All-Star.

Ruth naturally headlined the tour, walloping 13 home runs in 18 games (performing so well that a bronze statue of The Babe was later erected), and the tour was credited as a major factor for making professional baseball possible in Japan.

The Great Bambino launching home runs offered the perfect cover for Berg. Friday, November 29th was marked as the battle of All-Stars. The Major Leagues versus Japanese All-Stars in front of a full house. Moe Berg was nowhere to be found.

With Charlie Gehringer and Babe Ruth hitting home runs in that game, Berg was walking the streets of Toyko 17 miles away ostensibly undercover in a black kimono and hat. He stepped into St. Luke’s hospital carrying flowers for an Ambassador’s daughter and, speaking fluent Japanese, charmed his way to the seventh floor of the building.

Berg watched the hospital staff move about the floor, then calmly walked to an exit with a stairwell and climbed up to the roof. He set the flowers aside and took out a professional camera he had strapped to his body and started filming. He captured the skyline of the Japanese capital, the industrial areas, the Imperial Palace, and a number of intriguing locations from his vantage point.

Once the catcher was satisfied with his work, he strapped the camera back on his body, picked up his flowers, and left the building as calmly as he entered it – never even seeing the Ambassador’s daughter.

Berg soon gave these images to the United States government and into the 1970s it was believed his pictures were used as intelligence for the Doolittle Raid in the wake of Pearl Harbor (this claim was later refuted).

He retired from playing in 1939, serving a long if an undistinguished career as a ballplayer, and served as a coach for the Red Sox for 2 more seasons. Then came the day which lives in infamy. One month after Pearl Harbor, Moe Berg accepted a position with the Intelligence agency to counteract Axis propaganda in Central and South America.

Soon after he joined the Office of Strategic Services – the predecessor to the CIA. Berg bounced between countries and duties. From working in Brazil and Peru to monitoring Yugoslavia and the Balkans, going whenever his language, charisma, and impressive intellect were deemed necessary.

Counterintelligence

His greatest contributions during World War II undoubtedly came in 1944. Early in the year, he trekked into Italy to find the leading aerospace scientist Antonio Ferri. Berg found the Ferri hiding high in the mountains and shipped him to the United States where President Roosevelt remarked, “I see Moe is still catching very well.”

Thanks to this and his past performances, Berg was signed up for a highly classified mission deep in Nazi territory. His role in this project was to interview and listen to top Nazi scientists to determine how close Germany was to developing the Atomic Bomb.

He met with a Nobel Prize-winning physicist William Fowler and the President’s own scientific advisor Vannevar Bush to prepare (luckily Moe Berg already spoke fluent Italian, because of course he did). He also sat down with Albert Einstein to be briefed on nuclear physics, to which Einstein said, “Mr. Berg, you teach me baseball and I will teach you the theory of relativity,” but quickly changed his mind after talking with the catcher: “No, we must not. You will learn relativity faster than I will learn baseball.”

No amount of physics or training was above the catcher in this pursuit. “Moe was obsessed with tracking down the German scientists and pinpointing the enemy’s atomic bomb installations.” A colleague in the OSS said.

With the mission given the green light, Berg and the OSS attempted to lure the lead German scientist, Professor Werner Heisenberg, out of Germany by offering lecture opportunities or banquets, but to no avail.

That’s when Berg learned through a contact that Heisenberg would be serendipitously speaking at a Swiss university in Zurich. This would be the first time since the war began that Heisenberg left the borders of Germany.

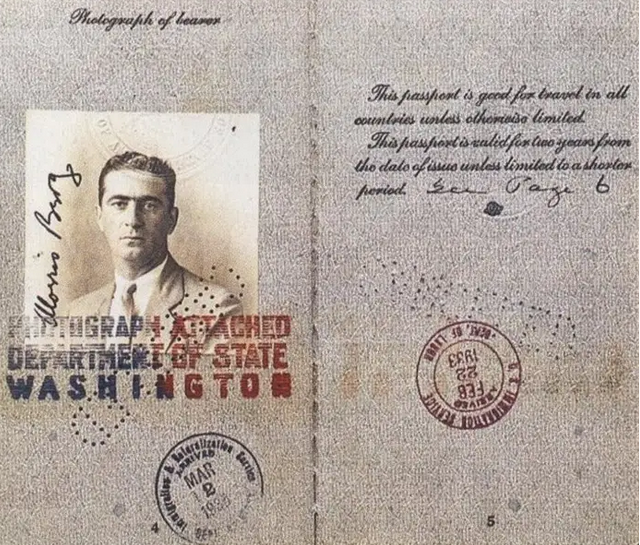

Moe Berg’s Passport – Public Domain

The catcher arrived in Italy in a submarine with an OSS granted pistol and a cyanide pill.

Berg posed as a Swiss graduate student attending the lecture and was given express orders: If it appears the Germans were working on the bomb, Berg was to assassinate Heisenberg and avoid capture at all costs, ordered to use the cyanide capsule if necessary to end his own life.

Berg sat through the lecture with a .45 caliber pistol in his pocket, waiting for any discernable hint that the Germans were on a threshold for the bomb, ready to kill the scientist that was surrounded on stage by Nazi soldiers.

The lecture was intense. Heisenberg talked physics like Ted Williams could talk hitting, and the professor nearly lost Berg on the subject of S-Matrix Theory. But the catcher stayed on track and ultimately made a faithful judgment call. The Germans were not close to developing the bomb, from what he could tell, and kept the pistol in his pocket that night.

Berg obtained an invitation to attend a small dinner with Heisenberg just a few nights after the lecture. Intent on listening for any hints, Berg again sat vigilantly at dinner, but instead of learning the Germans were closing in on the bomb, Heisenberg revealed he was certain of Germany’s defeat.

Berg left the dinner and sent his report directly to the White House. President Roosevelt reportedly said again of him, “Fine, just fine. Let us pray Heisenberg is right. And, General, my regards to the catcher.”

Moe was recommended the Medal of Freedom for his actions only for him to reject the medal.

Moe Berg: Person

World War II took a toll on everyone who was remotely involved, and Moe was no different. What was once a charismatic, quick-witted, and kind man was someone similar but lacking that twinkle in his eye.

Berg’s brother said of Moe,

I sensed a radical change in Moe’s behavior soon after he had come home from Europe. He was not the same affable Moe that I know. He had become snappish on occasion. That was not like Moe. I think the major reason for this change was his wartime work.

Moe never told me about his missions, but, when he showed me the vial of potassium cyanide he had to carry with him, I knew he had been in tough and dangerous spots.

Berg would exist in a sort of translucent state for the remainder of his life. He had the mind and knowledge of baseball to return to the dugout as a coach or manager but only lived in the periphery of the game.

He would watch games in New York and bump into old friends (Joe DiMaggio let Berg stay in his Manhattan hotel for a night. Berg took full advantage and stayed six weeks). This was the way of Berg’s life. He was called “America’s guest” for his constant stays at friend’s houses or family’s.

The newly minted CIA tapped Berg again for his services, this time for information gathering against the Soviet Union and their atomic bomb project. Instead of another harrowing adventure, the CIA paid Berg $10,000 for ultimately no information on the Soviets.

Berg tried practicing law and had some income here and there, but lived the rest of his life as a nomad, carrying only a toothbrush with him and an ever-present newspaper at his side. With debt piling up thanks to a failed business venture, Berg finally relented friendly nudging and decided to write an autobiography for some much-needed funds. The first meeting between Berg and the editor, however, was something from a bad dream.

“I’m delighted to meet you. I loved all your pictures.”

“Pictures? Who do you think I am?”

“Aren’t you Moe of the Three Stooges?” The editor said.

The deal fell apart right then and there and Berg never aspired to his previous heights again.

A world traveler, spy, prodigious learner, and an intellectual giant of baseball, Moe Berg’s heart was never far from the game. As he lay on his deathbed in New Jersey in 1972, he used his last words to ask the nurse, “how did the Mets do today?”

His sister later accepted the Medal of Freedom on his behalf when details emerged of his role in the war. A serialized essay was published in 1975 entitled, “Moe Berg: Athlete. Scholar. Spy.” which revealed much of his life through interviews of those that knew him (and where much of this research originates). Every few decades a new book appears focusing on his life, most recently culminating in a movie starring Paul Rudd in 2018 that appears more fictitious than bound to reality.

Berg was thought of well at the end, garnering tender eulogies from newspapers across the country when he passed. As the Boston Globe put it, “Goodbye, Moe Berg, in any language.”

Photo by Dustin Bradford/Icon Sportswire | Adapted by Doug Carlin (@Bdougals on Twitter)